Posted By Norman Gasbarro on October 28, 2016

Today’s post features an 1895 history of a Civil War regiment formed of men including Henry M. Kieffer, who was living in Killinger, Upper Paxton Township, Dauphin County, in 1860, and was the son of Dr. Ephraim Kieffer, a pastor of St. David’s Reformed Church in that place during most of the years of the Civil War. For that reason, is important as a reference for Millersburg and Upper Paxton Township at the time of the Civil War. It is especially important because Henry M. “Harry” Kieffer, who served as a Hospital Steward in that regiment, is mentioned as one of the chief contributors to the work.

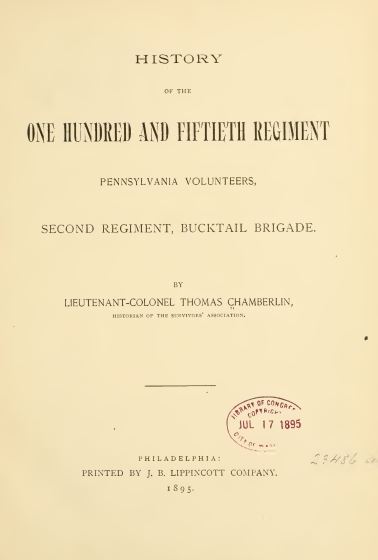

Chamberlin, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas (Historian of the Survivors’ Association). History of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Second Regiment, Bucktail Brigade [150th Pennsylvania Infantry]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1895.

This book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

For the convenience of readers of this blog, the Preface and Table of Contents (chapter list) are given here:

Preface

Now that nearly a third of a century has elapsed since the 150th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers gathered to the colors, when inquiry is made about the beginnings of the organization, the recollections of many of its most intelligent members are found to be more or less confused, and on some points quite unreliable. Is it that the infancy of a regiment, like that of an individual, has nothing in it of significant value to be remembered and preserved to posterity? Possibly not much. Yet, if even for a few of those still living who fought in the great War for the Union; or for the friends who were, for valid reasons, unable to share their trials, but watched with solicitude their progress in the field; or for the larger number of those who pride themselves on their descent from the patriotic actors in that grand tragedy, the birth and early movements of a particular military body have their interest, it is a sufficient warrant for noting in permanent form all that may be known of them.

It is scarcely a matter of wonder that the minute details of the organization of a regiment are so imperfectly recalled by its members. In the first days of his enlistment the eager soldier looks forward to the time of important deeds and chafes at every hour’s delay in town or camp. However seriously his ambitions may be modified by actual experience of warfare, his desire at the start is to meet the foe as promptly as possible,– to hear the rattle of musketry, the clash of sabres, the boom of cannon, and to snuff the intoxicating smoke of battle. All else is “rubbish.” Only after marching orders have set the machine of which he is a part in motion is the patient military “chronicler of small things” developed. Pocket annals blossom then on every side. Soon, however, the ardor of many would-be-historians is chilled as the strain of daily duty grows more severe, and of diaries it is presently only a question of the “survival of the fittest.”

After the transfer of the 150th from Harrisburg to Washington, the materials for a circumstantial account of its doings and experiences grow more abundant. It is the previous gap that is difficult to bridge over, But as some old and valued nurse is usually at hand to clear up misty points of family history or chronology, so there are still those left who stood in a manner as nurses to the infant organization, and, besides witnessing its birth, watched its growth, followed or shared the actions of its vigorous maturity, and continue to enjoy the memory of its achievements. From these have been gathered, as opportunity offered, many facts which — of of small general value — may prove interesting to the surviving members of the regiment and to their families and friends.

The narrative of the campaigns of the 150th — its tent life, marches, and battled — has been drawn from all available sources — chiefly from diaries kept by enlisted men and from letters written from the field, supplemented by the recollections of field-, staff-, and line-officers, as well as of the rank and file. Nothing has been set down without careful authentication, and where the memory of witnesses has clashed in respect to any important incident, everything possible has been done to reconcile the disagreement and reach the actual fact.

Acknowledgments are due to General H. S. Huidekoper and Brevet Major R. L. Ashhurst for the use of valuable private army correspondence; to Colonel George W. Jones, Captain H. K. Lukens, and Sergeant William R. Ramsey for many items of interest; to Adjutant William Wright for written accounts of the battles of the North Anna and Hatcher’s Run, and of the expedition to Fall Brook; to Rev. H. M. Kieffer, D.D., for copies of his weekly reports, as hospital steward, for the greater part of the year 1864; and to Sergeant Albert Mealey, Corporal George A. Dixon, and Frank H. Elvidge, all of Company A, for the loan of diaries,– that of Private Elvidge in particular, on account of its covering a longer period of time and entering more fully into the details of each day’s operations, proving the most serviceable contribution received from any quarter. Thanks are also due to many other members of the regiment for valuable suggestions and assistance from time to time as the work progressed, and to Mr. Ellicott Fisher, brother of the late Captain Harvey Fisher, of Company A, for the use of letters and papers left by the latter, relating to his army career.

If many matters are recalled by members of the command which find no place in this history,– such as instances of individual daring, humorous or pathetic happenings, unique experiences in camp or field,– their absence is explained by the fact that repeated requests for material of this kind received but a meagre response, to the regret of the writer, who knows the value of incident and anecdote in such a narrative. His work has been done painstakingly and conscientiously, in hours with difficulty snatched from an exacting business; and if his book, which is truly a labor of love, have no other merit, it is at least, or aims to be, a faithful presentation of the truth.

Philadelphia, 10 April 1895.

Table of Contents

I. Organization — The Philadelphia Companies………. 11

II. To Harrisburg — Regimental Organization………. 21

III. Concerning the “Bucktail Brigade” ………. 27

IV. On to Washington — In Washington ……….31

V. Social and Other Matters ………. 38

VI. Details and Duty — Breaking Up of the Camp ………. 42

VII. Washington in the Winter of 1862-1863 ………. 49

VIII. To the Front — Belle Plain ………. 55

IX. Various Happenings In and Out of Camp ………. 62

X. Night March to Fort Conway — Artillery Engagement at Pollock’s Mills ………. 72

XI. Chancellorsville ………. 80

XII. In Camp of White Oak Church ………. 91

XIII. To Gettysburg ………. 101

XIV. Gettysburg — First Day ……….. 110

XV. Gettysburg, To a Finish .,……… 131

XVI. Return to Virginia — From Pillar to Post ………. 146

XVII. From Centerville Back to the “Old Stomping Ground” — Warrenton Junction — Mine Run — Paoli Mills ………. 156

XVIII. Culpepper — Raccoon Ford — A Wound-be Incapable — An Appeal to Cesar — Resignations ………. 169

XIX. Across the Rapidan — The Wilderness ………. 182

XX. Laurel Hill — Spottsylvania ………. 193

XXI. The Affair at the North Anna — Topopotomov ………. 201

XXII. From Cold Harbor to Petersburg ………. 209

XXIII. Fort Sedgwick (or “Hill”) — Making Converts — Weldon Railroad …….. 222

XXIV. Fort Dushane — First Movement on Hatcher’s Run …….. 232

XXV. In Winter Quarters — Exchange of Arms — Presidential Election — Second Weldon Railroad Expedition — Second Hatcher’s Run (or Dabney’s Mill) ………. 243

XXVI. To Elmira, New York — Guarding Conscripts — Expedition to Fall Brook, Pennsylvania, and a Bloodless Victory — Muster Out and Final Pay — Home Again ………. 250

APPENDIX ………. 261

Category: Resources |

Comments Off on A History of the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry – Including Reports of a “Bucktail” from Killinger

Tags: Killinger, Millersburg, Upper Paxton Township

;

;