John Peters – Saved By Surgeons, Pensioned, But Died in Soldiers’ Home in 1886

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on October 21, 2016

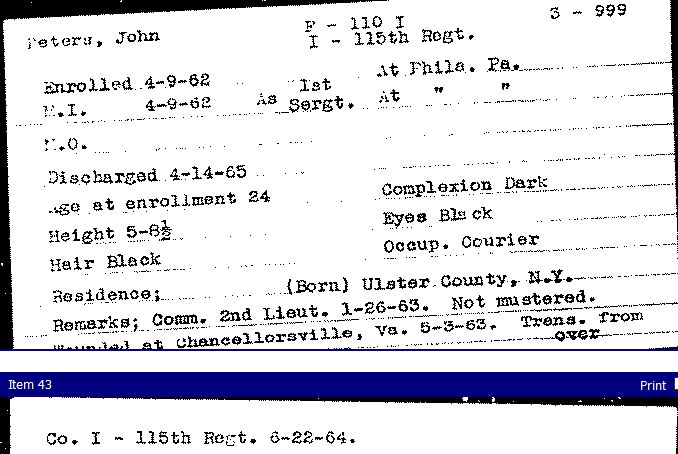

John Peters was born in Ulster County, New York, but when the time came to serve in the Civil War, he was in Philadelphia, and it was there that he enrolled in the 115th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company I, as a Sergeant, on 9 April 1862. Supposedly, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant on 26 January 1863, but was never mustered at that rank. He served until he was wounded at Chancelorsville, Virginia, on 3 May 1863, and following that injury, he recovered enough to return to service in the 110th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company F, with a discharge date of 14 April 1865.

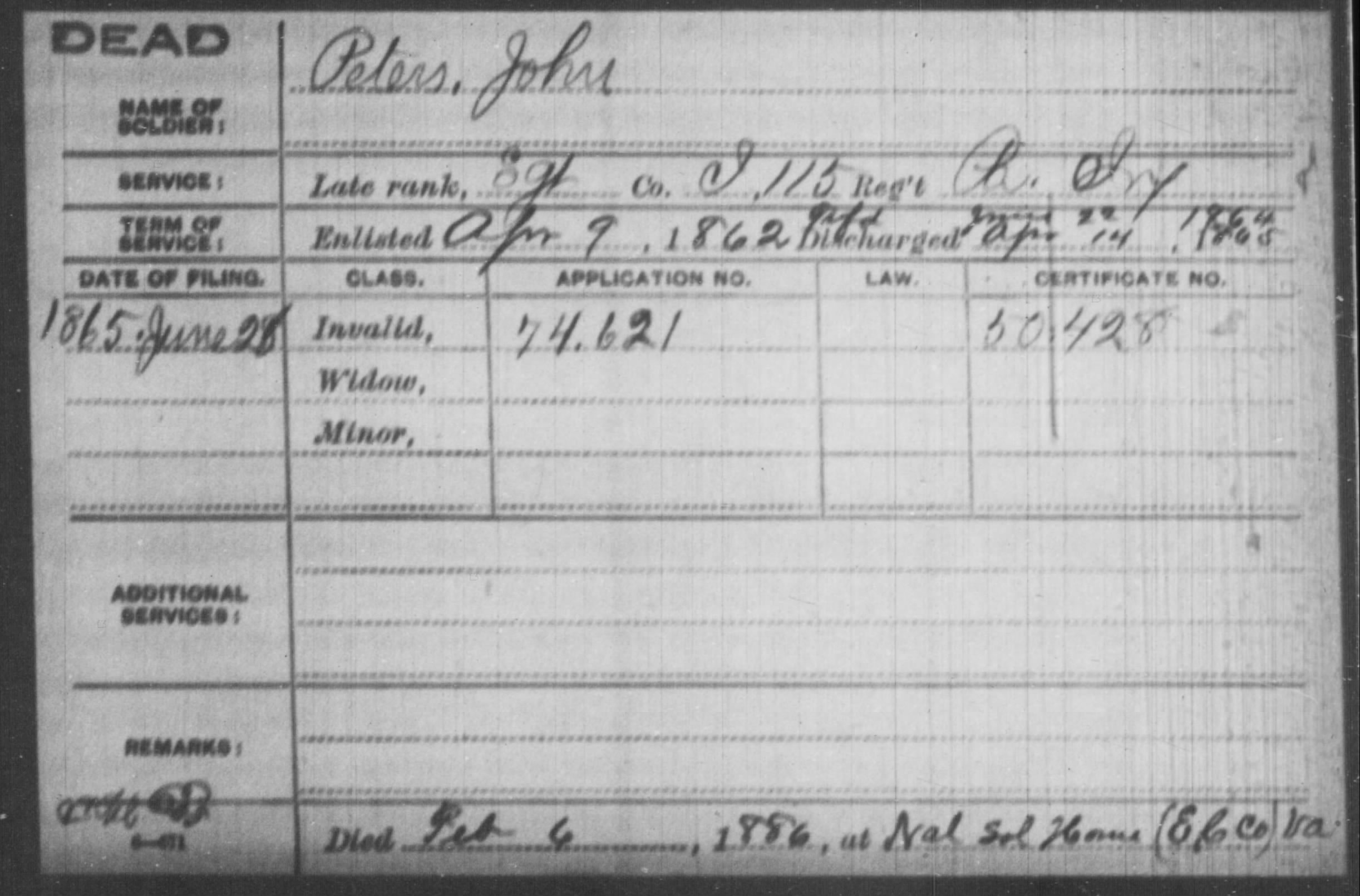

From his Pension Index Card (Fold3 version shown above), it is known that he applied for a pension on 28 June 1865, a little more than two months after his discharge. According to the card, he received the pension, but the card also notes that he died on 6 February 1882 at the National Soldiers’ Home in Virginia.

From these records, which are readily available on the web, it is not possible to tell much about how severely he was injured or how long it took him to recover. Some of that information may be in the pension application files, but because of the cost of obtaining them, they were not consulted for this blog post.

In 1867, Army Surgeon John A. Lidell compiled his memoirs from the records of the Stanton General Hospital, Washington, D.C., of which he was in charge. In addition to his own personal recollections, he used postmortem records, observations of friends, and material provided by the United States Sanitary Commission to produce a compilation of clinical reports relating to specific cases treated at Stanton General Hospital, many of which had not been previously published in the medical history of the war. Lidell’s memoirs were not published until 1870.

Harold Elk Straubling included a few selected cases from the memoirs of Lidell in his book, In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of Its Doctors and Nurses (Harrisburg: Stackpole Press, 1993).

Some of the medical record of John Peters is presented here. The gruesome details have been eliminated by ellipsis but are presented by Straubling on pages 89-93 of the aforementioned book.

Case XLV. Gunshot Fractures of Left Femur and also of Cranium; Necrosis and Exfoliation of a Fragment of External Table of Scull; Chronic Osteomyelitis of Femur; Several Fragments of Necrosed Bone; besides some Detached Splinters, extracted from Thigh.

Sergeant John Peters, Company I, 115th Pennsylvania Volunteers, aged 25 years, was admitted to the Stanton U.S. Army General Hospital on 15 June 1863, for gunshot injuries. He state that he was wounded on 3 May in the Battle of Chancellorsville by a minie ball, which passed through his left thigh…. When admitted to the hospital… the thigh was swollen and inflamed, and the wound suppurating profusely….

He had besides, a compound… fracture of the scull…. The scalp-wound was about two inches in length and one in breadth. The depressed portion of the bone was about the size of a half-dime…. He states that his left side was paralyzed for about two weeks after the reception of the wound…. He complains of having some frontal headache, and pain shooting in the direction of his right eye…. His general condition is not promising. His tongue is red and dry; his pulse frequent and feeble, his spirits are somewhat depressed, and he has but little appetite….

17 June 1863 – He had a chill, followed by a fever and sweating….

20 June 1863 – His general appearance has improved. The head wound looks well…. The thigh wounds are also doing well….

27 June 1863 – The wound of the head is again suppurating, and he has no fever…

12 July 1863 – He complains of having pain in the foot, which prevents sleep. Directed morphia sulph[ate]… to be administered at night….

10 August 1863 – His condition is much improved. The head-wound looks well. The fracture of the femur has united; but necrosed bone is discernible on exploration of the thigh wound.

30 August 1863 – He has rigors and fever in the afternoon….

5 September 1863 – He complains of pain in his right side, is restless, has cough, and there is course crepitation in his right lung….

8 September 1863 – His condition is much improved. The pain, cough, and crepitation in the chest have ceased….

11 September 1863 – There is swelling, redness, and pain in his thigh. Order the lead and opium wash to be applied to it.

12 September 1863 – The pain, redness, swelling, and tension of his thigh have increased. Free incisions were made (long and deep), a quantity of us evacuated and relief afforded.

14 September 1863 – His general condition is much improved.

20 September 1863 – Wound of head is healed; abscess of thigh filling up with healthy granulations….

20 December 1863 – He complains of debility and want of appetite….

13 February 1864 – He has diarrhoea….

16 February 1864 – The diarrhoea is checked….

14 April 1864 – The patient was transferred to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, being in good flesh and spirits, and abundantly able to stand the journey. The injure limb is recovering from the atrophy occasioned by long disuse, that is, it is increasing in size, and the patient is rapidly regaining the use of is. The limb was shortened just three inches.

Other than the transfer to the 110th Pennsylvania Infantry as noted on the Pennsylvania Veterans’ Index Card previously mentioned (from the Pennsylvania Archives), not much more is reported about John Peters‘ military service until his discharge on 14 April 1865 . The injuries he received were apparently severe enough that he was forced to apply for disability benefits on 28 June 1865. While he was granted those benefits, there is also evidence that he was not able to take care of himself, because as early as 1867, he appeared in the Soldiers’ Home records at Dayton, Ohio, and after that he was transferred to the home at Hampton, Virginia in 1871, where he died on 8 February 1886.

Little else is known about John Peters, his background, and his experiences in the Civil War. But the medical records of the war, as well as the memoirs of doctors who served, do provide a resource that heretofore has not been fully utilized in genealogical research, as this one example shows.

Additional information is sought on how soldiers recovering from war-related injuries were treated in the hospitals of the time. Appropriate comments can be attached to this blog post.

;

;

Comments