James Ferguson – An Army Surgeon’s Story to Save His Life

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on October 10, 2016

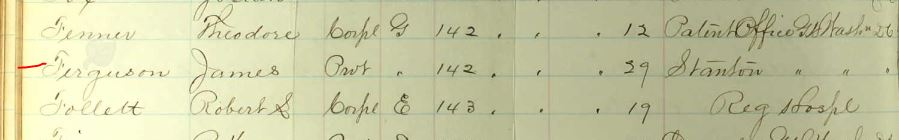

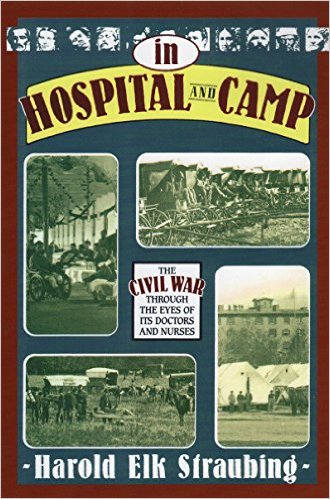

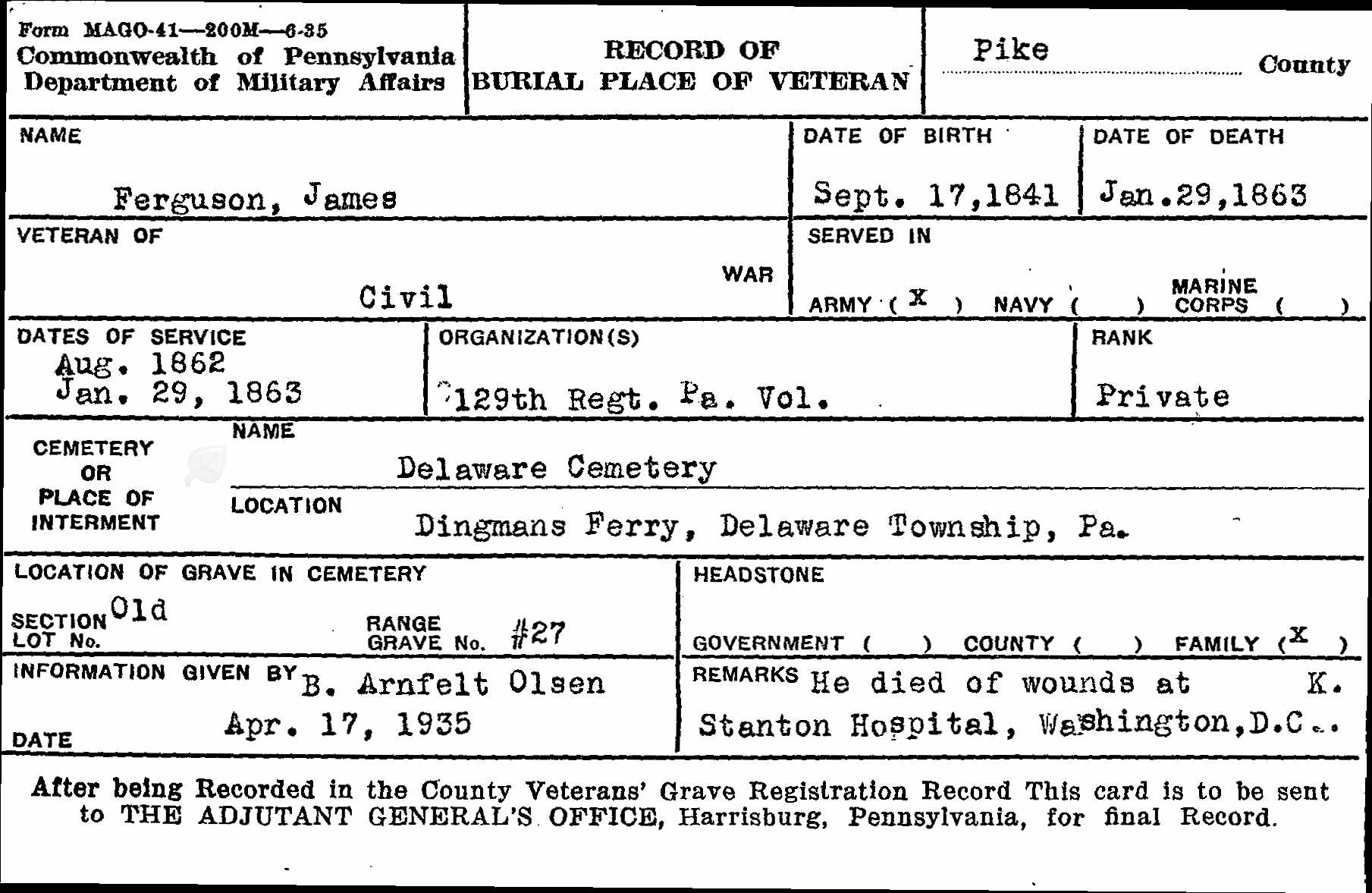

On 29 January 1863, according to the U.S. Register of Deaths of Volunteers, James Ferguson, a Sergeant of the 142nd Pennsylvania Infantry, Company D, died at the Stanton General Hospital, Washington, D.C., of “vulnus sclopet,” an abbreviation of the Latin term, vulnus sclopeticum, for “gunshot wound.” The treating surgeon who verified the death was John A. Lidell.

James Ferguson, had enrolled in the 142nd Pennsylvania Infantry on 11 August 1862 at Stroudsburg, Monroe County, Pennsylvania. The military records as well as the roster of volunteers show that he was wounded at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on 13 December 1862.

In 1867, John A. Lidell compiled his memoirs from the records of the Stanton General Hospital of which he was in charge. In addition to his own personal recollections, he used postmortem records, observations of friends, and material provided by the United States Sanitary Commission to produce a compilation of clinical reports relating to specific cases treated at Stanton General Hospital, many of which had not been previously published in the medical history of the war. Lidell’s memoirs were not published until 1870.

Harold Elk Straubling included a few selected cases from the memoirs of Lidell in his book, In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of Its Doctors and Nurses (Harrisburg: Stackpole Press, 1993).

Some of the medical record of James Ferguson is presented here. The gruesome details have been eliminated by ellipsis but are presented by Straubling on pages 86-88 of the aforementioned book.

Case LXIV. Gunshot Wound of Right Leg (Calf) in Upper Third; Secondary Hemorrhage on Forty-First Day; Litigation of Femoral Artery.

Sergeant James Ferguson, Company G, 142nd Pennsylvania Volunteers, a young man of good constitution, was admitted to Stanton U. S. Army General Hospital, 29 December 1862, sixteen days after the First Battle of Fredericksburg, on account of a gunshot wound of the right leg, received in that battle, 13 December….

The wound did well until the middle of January, when the granulations assumed an unhealthy appearance and the discharge became thin and serous. He also exhibited typhoid symptoms, having a hot skin, a frequent pulse, a dry, red tongue, watchfulness and no appetite….

On the afternoon of… Sunday, 25 January 1863, forty-three days after he had been wounded the patient was manifestly pyaemic, and we scarcely hoped for his recovery on that account….

Monday morning, 26 January- Patient appeared brighter… leg getting warm, down to the ankle…. Six P.M., foot cold; blackness extending across the leg in track of wound; tongue dry, has had a slight chill, and he is somewhat delirious….

Tuesday, 27 January – Morning. Patient looks better than last evening… leg warmer and blacker; foot pale and swelled… and discoloration extends up the thigh.

Wednesday, 28 January – Patient presents a pale, yellow hue; blackness of limb deepening and extending; has reached the lower end of the incision… odor gangrenous.

Thursday, 29 January – Patient sinking; and he died in the evening….

The autopsy showed that the bleeding came, not from the posterior tibial… but from the popliteal artery, which had been opened to large extent by ulceration. It was also found that the ball had grazed the hind part of both the tibia and fibula in its track, and there were some loose splinters, small in size, in relation with the tibia and fibula.

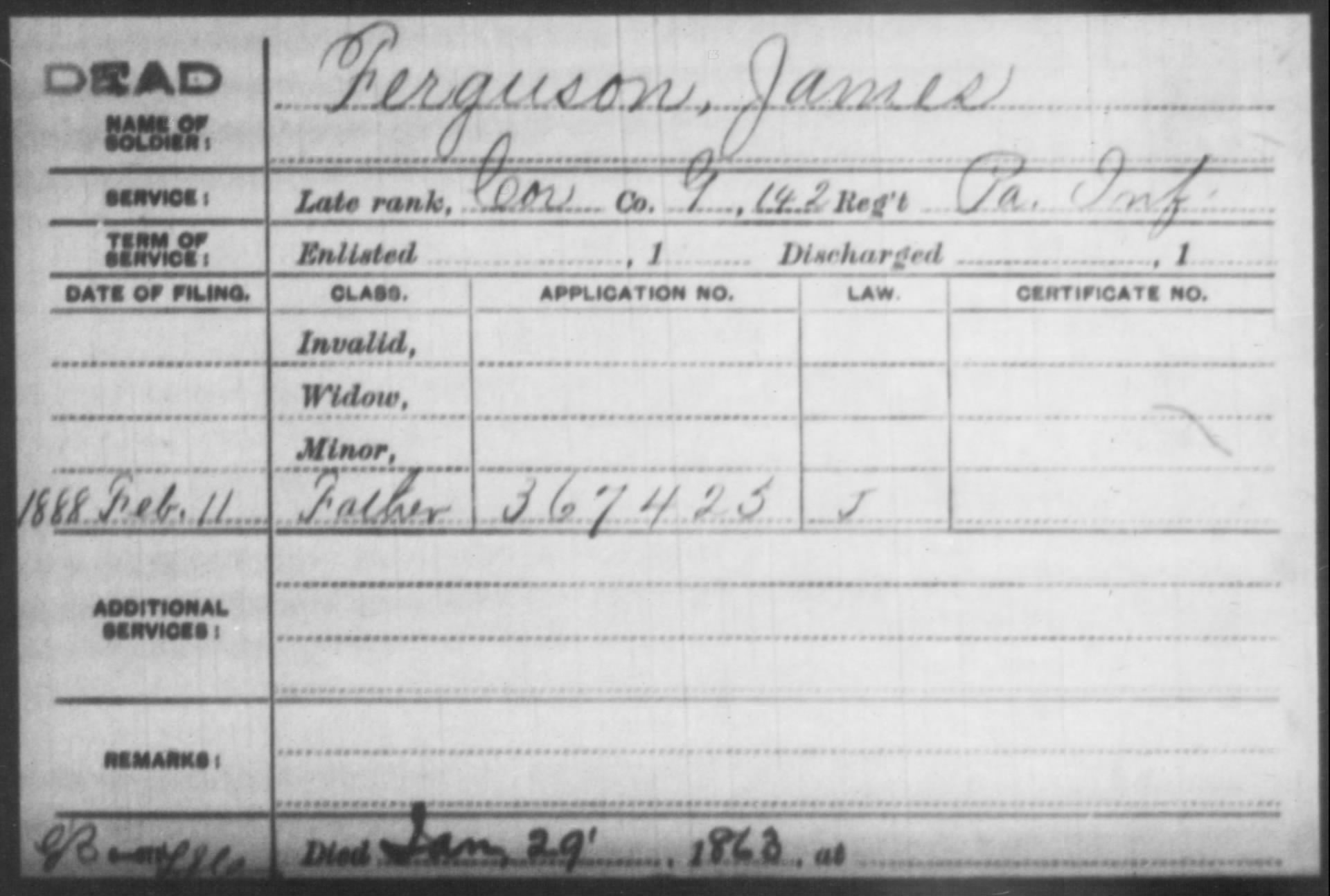

The Pennsylvania Veterans’ Burial Card, shown above from Ancestry.com, gives incorrect information about the regiment in which James Ferguson served, but has other information helpful in determining more about him. He was born on 17 September 1841 and his death date as well as place and cause of death is correctly stated. According to the card, he is buried in Delaware Cemetery at Dingman’s Ferry, Pike County, Pennsylvania. However, at this time, there is no Findagrave Memorial for him, although there is another person of that name who is buried in that cemetery.

What is known for certain is that there were no immediate survivors who applied for pension benefits.

However, on 11 February 1888, the father of James Ferguson applied for survivor benefits, which the record card (shown above from Fold3) indicated that he was not awarded. From the Ancestry.com version of the card (not shown), the father’s name was Edward A. Ferguson and the application was made from New York State.

Little else is known about James Ferguson, his background, and his experiences in the Civil War. But the medical records of the war, as well as the memoirs of doctors who served, do provide a resource that heretofore has not been fully utilized in genealogical research, as this one example shows.

If any readers can provide stories on how medical records have helped them in their family history research or can suggest other resources related to the same, please add the information as comments to this post!

;

;

Comments