The Great Shohola Train Wreck – First Newspaper Reports

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on April 24, 2014

Today’s post is the second installment of a series on The Great Shohola Train Wreck. Some of the early newspaper accounts from Pennsylvania newspapers are presented.

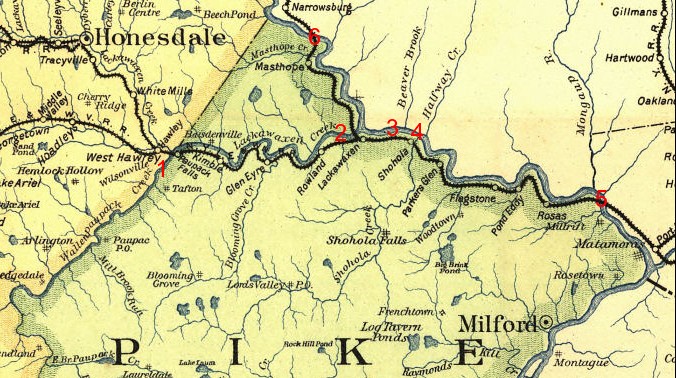

On 15 July 1864, at about 2 P.M., a train carrying 833 Confederate prisoners of war and a contingent of Union guards, collided head-on with a 50-car coal train on a single-track main line of the New York and Erie Railroad. The collision occurred about one-and-a-half miles west of the small village of Shohola, Pike County, Pennsylvania. The train carrying the prisoners was headed west from Jersey City, New Jersey, to the newly-established prison camp at Elmira, Chemung County, New York. The coal train was headed east from the Hawley branch railroad and was hauling coal from the vast anthracite coal fields of central Pennsylvania to the New York area. It was the greatest railroad disaster of the Civil War – and to that point in time, the greatest recorded railroad disaster in history. Forty-eight prisoners and seventeen Union guards were killed in the accident and many more were seriously wounded.

The crash of the trains occurred at #3 on the map above.

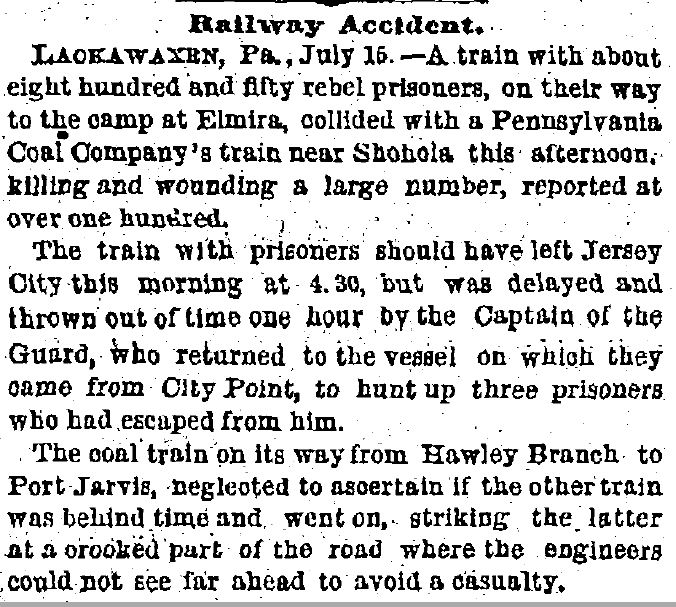

An early news story of the accident appeared in the Philadelphia Daily Age, on 16 July 1864:

Railway Accident

LACKAWAXEN, PA, 15 July 1864 — A train with about eight hundred and fifty prisoners, on their way to the camp at Elmira, collided with a Pennsylvania Coal Company’s train near Shohola, this afternoon, killing and wounding a large number, reported at over one hundred.

The train with prisoners should have left Jersey City this morning at 4:30, but was delayed and thrown out of time one hour by the Captain of the Guard, who returned to the vessel on which they came from City Point, to hunt up three prisoners who had escaped from him.

The coal train on it way from Hawley Branch to Port Jarvis [Port Jervis], neglected to ascertain if the other train was behind time and went on, striking the latter at a crooked art of the road where the engineers could not see far ahead to avoid a casualty.

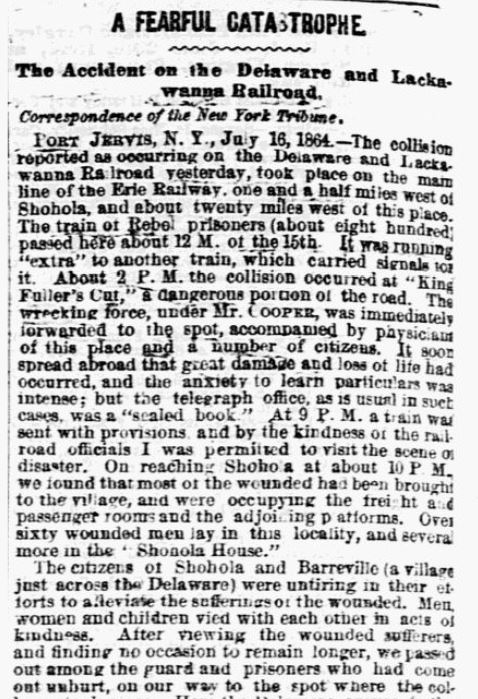

A more detailed explanation of the train wreck was supplied to the readers of the Philadelphia Inquirer on 19 July 1864, re-told by a correspondent of the New York Tribune who had gone to the scene just after the accident occurred:

A FEARFUL CATASTROPHE

The Accident of the Delaware and Lackawanna Railroad

Correspondence of the New York Tribune.

PORT JERVIS, N.Y., 16 July 1864 — The collision reported as occurring on the Delaware and Lackawanna Railroad yesterday, took place on the main line of the Erie Railway, one and a half miles west of Shohola, and about twenty miles west of this place. The train of rebel prisoners (about eight hundred) passed her about 12 M. of the 15th. It was running “extra” to another train which carried signals for it. About 2 P.M. the collision occurred at “King Fuller’s Cut,” a dangerous portion of the road. The wrecking force, under Mr. Cooper was immediately forwarded to the spot, accompanied by physicians of this place and a number of citizens. It soon spread abroad that great damage and loss of life had occurred, and the anxiety to learn particulars was intense; but the telegraph office, as was usual in such cases, was a “scaled book.” At 9 P.M. a train was sent with provisions and by the kindness of the railroad officials I was permitted to visit the scene of disaster. Upon reaching Shohola at about 10 P.M. we found that most of the wounded had been brought to the village, and were occupying the freight and passenger rooms and the adjoining platforms. Over sixty wounded men lay in this locality, and several more in the “Shohola House.”

The citizens of Shohola and Barreville [Barryville, New York] (a village just across the Delaware) were untiring in their efforts to alleviate the sufferings of the wounded. Men, women and children vied with each other in acts of kindness. After viewing the wounded sufferers and finding no occasion to remain longer, we passed out among the guard and prisoners who had come out unhurt, on our way to the spot where the collision took place. Here the Delaware curves to the northward and the railway follows its banks, the convexity of the curve being the same as that of the river. An intervening hill shut out the approaching trains from each other, so that it was impossible to discover one another until within a hundred yards of each other. Indeed, by mounting the wrecked engines, it could be seen that it is almost impossible for the westward-bound engineer to seen an approaching train until the very moment of collision. The last of the dead had been removed from the wreck and lay in ranks by the side of the road, in the edge of a rye field.

The shock of collision was fearful. Two noble engines were almost entirely demolished, the “171” and the “237.” The tender of the “171” was heaved upon end, hurling its load of wood into the cab, effectually walling in both engineer and fireman against the hot boiler, and crushing them terribly. Both were found standing at the their post, dead. This was the train carrying the prisoners. The first two or three cars were box freight cars, and their frail frames were crushed like rushed. Only one man was saved from the forward car. In the others very many were wounded, and scarcely a car escaped without being crushed. The most industrious endeavors were at once put in requisition to relieve the mangle beings in the wreck. But it was slow work, and their sufferings were intense. As fast as possible the wounded were carried to Shohola, and the dead placed beside the road.

On the bank near the engines lay some twenty-five Rebel dead – many mangled past recognition. Another squad, of as many more, lay further down the road; and still further, wrapped in blankets lay fourteen of the guard – their duty done forever. Viewed by moonlight, and with lantern it was a ghastly and horrible sight, although kindly hands had done much by coverings of leaves, & c., to relieve the horror of the scene, and the ghastliness of the dead. As we left, Mr. McCormick, wood agent and paymaster of the Delaware division, had arrived with pine boxes for the burial of our own dead. This morning all were buried on the spot, and the graves marked for future recognition. The Rebel dead were also decently interred in pine boxes.

The best account I can get, and which is wholly trustworthy, may be summed up as follows: – the coal train eastward, bound from Hawley takes the main track from the branch at Lackawaxen. The conductor went to the telegraph office at Lackawaxen, as usual, and inquired if the way was clear to Shohola (a distance of about four miles). The operator replied that it was clear to Shohola and the coal train proceeded at its usual rate to meet the mail train at eight at its usual passing pace. The train which had carried the flag for the train of prisoners had passed Lackawaxen some hours before, and the operator was aware of the fact, and had not long before given a train notice of the fact; so I was told.

Thus the coal train, consisting of fifty loaded cars was proceeding at the rate of twelve miles per hour, thinking it all right and the other train hurried on its way in fancied security, dashed into the former at twenty miles per hour, and the loss of life and property was the consequence. The tender of the coal engine was lifted several feet into the air by coal cars rushing beneath it. The engineer catching a glimpse of the approaching train in the cut jumped for his life, and saved himself.

The casualties are, the engineer of the “171,” his fireman, the fireman of the “237,” and a flagman killed. At the hour of leaving the wreck (1 A.M.) sixteen Union soldiers, and nearly fifty Rebels, were dead, nearly all taken from the wreck with life extinct. The wounded cannot, I think, fall far short of seventy-five to eighty men.

All the blame seem to be traced to the telegraph operator who is spoken of as a drunken fellow by all who have mentioned him to us. It was said he was intoxicated the night before the accident, and it was nothing unusual for him to be in that condition when assuming his post of duty. It is said that he has disappeared.

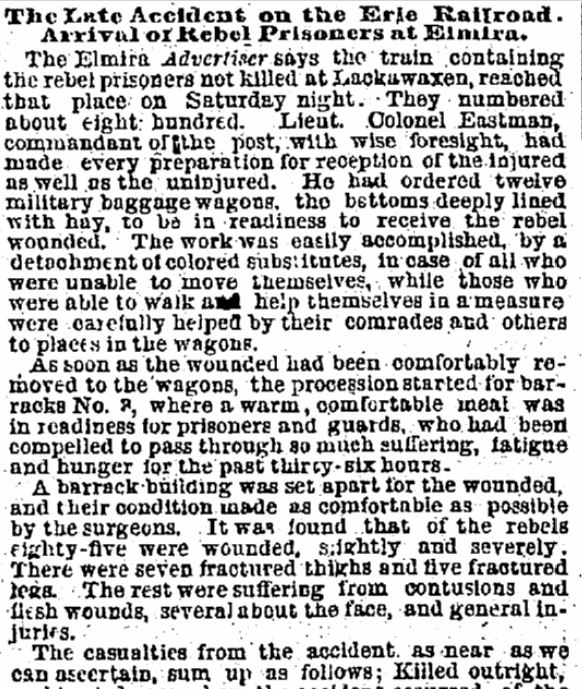

The telling of the story continued on 23 July 1864 in the Philadelphia Daily Age, which reported from complied reports including from the Elmira Advertiser:

The Late Accident on the Erie Railroad.

Arrival of Rebel Prisoners at Elmira.

The Elmira Advertiser says the train containing the rebel prisoners not killed at Lackawaxen, reached that place on Saturday night. They numbered about eight hundred. Lieutenant Colonel Eastman, commandant of the post, with wise foresight, had made every preparation for reception of the injured as well as the uninjured. He had ordered twelve military baggage wagons, the bottoms deeply lined with hay, to be in readiness to receive the Rebel wounded. The work was easily accomplished, by a detachment of colored substitutes, in case of all who were unable to move themselves, while those who were able to walk and help themselves in a measure were carefully helped by their comrades and others to places in the wagons.

As soon as the wounded had been comfortably moved to the wagons, the procession started for Barracks No. 3, where a warm, comfortable meal was in readiness for prisoners and guards, who had been compelled to pass through so much suffering, fatigue, and hunger for the past thirty-six hours.

A barrack building was set apart for the wounded, and their condition made as comfortable as possible by the surgeons. It was found that of the rebels, eight-five were wounded, slightly and severely. There were seven fractured thighs and five fractured legs. The rest were suffering from contusions and flesh wounds, several about the face, and general injuries.

The casualties from the accident as near as we can ascertain sum up as follows: Killed outright, and buried near where the accident occurred, of the Rebels, forty-eight; left behind at Lackawaxen, unable to be moved or brought on by train, fifteen; brought on by the train, eighty-five – making in killed and wounded, one hundred and forty-eight. Of our men of the Veteran Reserve Corps, killed and buried at the place of the accident, seventeen; brought on and put in the hospital, suffering only from bruises and contusions, ten; left behind, unable to be moved, eight – making in all thirty-five.

Scarcely a guard escaped destruction who was sanding on the platforms between the cars. One found himself over in an oatfield, severely bruised, after the accident, while his companions were crushed instantly. The muskets were broken and mashed and the barrels twisted and bent double. These were brought along as sad relics. The passenger cars of the train, some sixteen in number, were completely demolished, and another new train had to be made up of common box cars, spread with straw at the bottom, upon which the inmates managed to ride the best way they could.

—————————–

News articles are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The map is modified from one that appears on the site Pennsylvania Railroad Stations Past and Present.

To see all the posts in this series, click on ShoholaTrainWreck.

;

;

I grew up in Matamoras, Pa across the Delaware River from Port Jervis NY. I served 24 years in the Navy and 2 tours in Iraq with NMCB-21 Jacksonville Fl. In my opinion this so called Great Train Wreck sounds suspicious. Everyone is negligent from Jersey City to the dispatcher that fled the sene of a crime. The timing of the events that lead up to the accident are impeccable. In 1864 the country was desperate in many ways. This smells like a revengeful hostile act of sabatoge. I believe a serious war crime was committed. When I was a child I remember digging in an old dump looking for old bottles with my father. The dump was next to an old house in Shohola pa. Not far from this Civil War Train Wreck. Next to my father sticking out of the ground was a civil war sword handle. My father pulled it out of the ground and the entire sword was attached. Not realizing what I had at the time, I decided to sell it for $20.00 to an antique dealer in Milford Pa. I wish I had the sword now. 45 years has passed since then, czbianchi@yahoo.com