The Susquehanna River Flood of March 1865 (Part 2 of 2)

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 11, 2014

This post concludes a chronicle of the worst flooding on the Susquehanna River in history – at least at the time that it occurred. The text is featured from two contemporary newspaper articles which provided information on the extent of the damage.

———————————-

From the Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 March 1865:

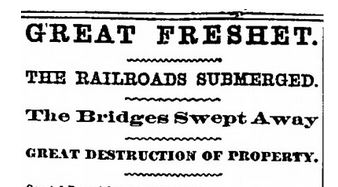

GREAT FRESHET. THE RAILROADS SUBMERGED. The Bridges Swept Away. Great Destruction of Property.

Special Despatches to the Inquirer.

Harrisburg, 17 March 1865 — The flood in the Susquehanna is said to be fully equal to that of 1846. Although the river was very high yesterday, it commenced rising rapidly during the night, so that today fears are entertained that the Cumberland Valley Bridge will go down. At the eastern terminus of the bridgte the water is washing the wood work, while at the western terminus it is within eight feet of the edge. The engineer’s room in the water-house is flooded and all engines have stopped working. All the islands in this vicinity are submerged. A small tenement came down this morning.

The Paxton Creek, skirting the eastern portion of the town, is trying to emulate the river, the water having backed upt the stream and partly submerging a number of houses. Nearly all the railroads centering here are obstructed by the flood. At many places along the river the tracks are submerged in from three to five fet of water. It is reported here that the bridge over the Susquehanna at Northumberland has been sept away, but as the telegraph line north and west is down, it is impossible to ascertain the truth. The banks of the river present quite a scene of excitement.

Additional Particulars.

Harrisburg, 6 P.M. — The Cumberland Valley Bridge is still standing, though the water is rising against it. A larger portion of the lower and eastern end of the town has been submerged since my last. Many families are moving to more elevated positions. It seems well settled that the Clark’s Ferry Bridge over the Juniata at the junction has gone down.

The eastern trains on the Pennsylvania Railroad are all stopped.

They cannot even avail themselves of the Mount Joy Branch, owing to the fact that the road is covered by over four feet of water between this and Elizabethtown. A train left here for Pittsburgh at noon. The mails for Pittsburgh arrived here by Lebanon Valley Railroad. A Northern Central train reached here from the South, having run over a bridge covered by two feet of water at New Cumberland.

A portion of Paxton Street, a great part of Front and Market, and all the streets west of Sixth are partly or wholly submerged. The water is now, six and a half o’clock twenty feet above low water mark, by the register at the city water house.

A vast amount of lumber and articles of many descriptions are passing down the river, showing that great loss of property must have taken place above.

Later.

Harrisburg, 17 March 1865 – 7 P.M. — A span of a bridge has just passed down the river on the western side, supposed to be from Duncannon. A span of the Clark’s Ferry Bridge has been knocked out.

—————————-

From the Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 March 1865:

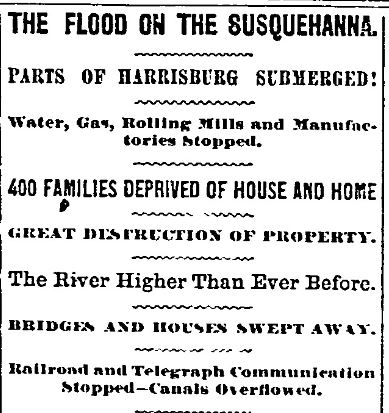

THE FLOOD ON THE SUSQUEHANNA. PARTS OF HARRISBURG SUBMERGED! Water, Gas, Rolling Mills and Manufactories Stoped. 400 FAMILIES DEPRIVED OF HOUSE AND HOME. GREAT DESTRUCTION OF PROPERTY. The River Higher Than Ever Before. BRIDGES AND HOUSES SWEPT AWAY. Railroad and Telegraph Communication Stopped – Canals Overflowed.

Special Correspondence of the Inquirer.

Harrisburg, 18 March 1865 — The Susquehanna is a stream of romantic beauty in placidity, and with its adjunct of the “Blue Juniata” it may be said to traverse a country almost surpassed in grandeur and magnificence of scenery. But when its currents are swollen by rains, and its elements vexed by lashing winds, the placid “winding river” becomes terrible in its impetuosity.

It sweeps by vale and woodland, by town and hamlet, past valley gorge and mountain cliff, like one mad, rushing to eternity, as a besom of destruction.

The Flood of 1846

Such a flood there was in 1846, to which those who can recollect it refer as the “Great Flood.” which swept trees, boats, houses, and almost every conceivable article of property in its onward course. According to the register at the Harrisburg Water House, the water had then attained a point twenty-two feet above low water mark. In the long years since then not another flood like that has occurred until now.

The Flood of 1865.

For several days past the river had been in a swollen state, owing to the thaw of ice and snow on its bosom, in its tributaries and along its banks, the late heavy rains contributing much to its volume. But the ice, so much dreaded, had passed down without doing much material damage and it was thought the worst was over. Much anxiety had been manifested, but now people congratulated themselves on their probable escape from another “great flood.”

Rate of Rising – The Great Volume

But the river, fickle main, alas! was indeed most viciously disposed. Early night before last, contrary to the usual order of things, she rose and commenced rising in a very bad humor. At seven o’clock yesterday morning the water had reached nineteen feet above low water, and at seven in the evening it had reached twenty-four feet eight inches, eighteen inches higher than in 1846. Some idea of the rapidity of increase in volume, may be gathered from the fact that during the space of eleven minutes of the watch, the river had risen three inches. From nine to four o’clock nigh before last, it rose two feet, and continued to rise at the rate of seven inches per hour.

Between two and six o’clock yesterday afternoon there was a rise of some twenty inches, being a decrease of rate as to height attained but not as to volume.

The City Water Works Stopped

Early in the morning the engine room of the City Water Works was submerged, the fires extinguished, and the engines stopped working. The Mayor deemed it necessary to issue proclamation to the citizens, requesting them to abstain from unnecessary use of water as the supply in the reservoirs was very low. The water was afterwards shut off, except between the house of six and eight A. M.

The Railroad Bridge.

Fears were entertained for the safety of the bridges across the Susquehanna here. The Cumberland Valley Railroad Bridge was deemed in imminent danger. This bridge is somewhat lower than the road bridge, having a descending grade from the western to the eastern shore o about nine feet to the mile. The water was rapidly approaching the woodwork, until at about twelve o’clock M—— was kissed by the spray at the eastern terminus. Increasing in volume, the water soon rose higher against the structure.

Logs, trees and timber in all shapes came rushing down with the rolling torrent at the rate of about eight miles per hour. It was curious to see, as they approached the bridge, how they appeared like military battering rams, bent on a war of extermination. They seemed to prepare themselves for the occasion. Now and then, a sleek, fat “boom log: would come sailing along like a clipper ship, and nearing the bridge, would pose itself for the attack, and go crashing through the weather-boarding and timber much to the delight of the urchins assembled, and then dive under, to reappear on the other side, on is voyage to the Chesapeake. But the bridge stood these damaging attacks most manfully.

The City Inundated

Meanwhile, the water was fast invading the lower portions of the city. The much-dreaded back-action on the Paxton Creek had commenced. Soon the water overflowed the bank of the little stream, submerging the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge across it. Its encroachments now reached the city limits. The Paxton and Lochtel Iron Works were deluged, and quite a little town of working men, who had earned their little homes by years of toil, lost their all. They fled from the scene in terror, women and children, wandering in every direction, in want and poverty.

This indeed was sad. As the inundation spread the distress increase. From the upper end of the town to the extreme lower terminus of the creek the water had formed quite a lake, submerging the houses between Sixth Stree and Allison’s Hill. Families moved to the upper stories or entirely deserted their homes. Boats and stray planks became their means of locomotion from place to place. Thousands of dollars of property was destroyed. And this, we are told, is but one of the many instances of damage and distress along the banks of the river.

The Excitement.

The scene , indeed, beggars description. Stretched along the banks of the steam, and along the borders of inundated districts, were men, women and children, gazing upon the turbid torrent as it rolled past them, in awe and silence betimes,, as if the river were a living thing, a demon, bearing on its bosom the stains of a hundred murders. As of fire so may be said of water when it becomes master.

Stretching as far as eye could reach, almost, was the yellow, muddy element, raging and roaring where it met with obstacles, like the billows of a troubled sea, spitting its white foam in mad glee. An immense concourse of people were intent upon watching the bridge and the mad capers of the floating timber. It was not thought the bridge could possibly stand so long. A large island in the middle of the river, on which is a farm house and large barn, was entirely covered by the raging element, and bystanders busied themselves discussing the probable fate of live stock stabled in the barn.

A report was current, notwithstanding the absence of communication by telegraph, that the bridge over the North Branch at Northumberland had been swept away, and the inquiry was momentarily propounded, “What effect will it have upon our bridge when it comes sweeping down?” IN the morning a block-house — one of those erected by the Pennsylvania Railroad during the raid last summer – came down on the western side, and hitting a pier of the bridge, was knocked to pieces in a twinkling. “Good-by, block-house!”

About half-past six in the evening a span of a bridge came down, but on the western side, where it could pass under the railroad bridge. Old water-men stood by, with arms folded, coolly watching splendid logs passing. They did not exert themselves for their capture, because of the miserable pittance allowed by act of Legislature for the risk of life and limb. This act was passed after the flood of 1853, at the instance of the boom corporations along the upper branches, who wished to recover their timber at as little expense as possible, and this had given great offense to the river men.

Bystander to urchin, catching small timber – “There’s a large log passing you, bub.” “Don’t want it; boom log.”

The Night Scene.

And so the day passed, until night, with her mantle of darkness, covered the scene; and even then crowds lingered near the bridge, like ghostly sentinels, awaiting the fall of the structure. About nine o’clock, a train of passengers passed over slowly and cautiously, to avoid, to avoid a too great shock to the timbers. The river was still rising, and the logs and timbers were forming a dam against the bridge. It was manifest that the strain was becoming too much for the bridge, and about half-past nine it gave a loud groan of pain, and groan succeeded groan.

As the bridge would make these manifestations shouts would ascend from the crowd on shore. The scene in Schiller’s Brave Men could not have been more animating, only there was no particular terror here to lend enchantment to this midnight scene.

Signal lights were waved along the road. At every creak of the timbers a guage would be taken of the extent of the damage. A terrific wind from the west prevailed, driving the drift against the eastern shore, and lashing the water in foam crests against the bank and bridge.

Saturday Morning.

This morning dawned clear and beautiful with a prevailing wind from the west. It was found that the river had risen some two feet during the night. It was now twenty-five feet and a-half above low water mark, in an increase of three feet six inches over the flood of 1846.

The Market was slimly attended, the countrymen not being able to reach the city.

The Bridge.

Contrary to all expectations, [the bridge] was still standing, though its timbers were strained and shattered. It had moved some twenty inches during the night, notwithstanding the stays contrived to keep it in its place. Huge ropes were tied to it, connecting with trees on the land, drawn at tight tension, and several cars, loaded with iron, were placed upon the top to keep it down. The logs and timbers had caught in the trestle-work below, forming a dam, at the eastern terminus.

At present the bridge is still standing, with the water at a stand-still. Several spans came down at about nine o’clock, crashing through underneath the bridge. No fears are entertained in regard to the old carriage bridge, which is much higher and stronger. The water, however, is sweeping with great velocity and depth over the island between the two portions of the bridge, which presents the appearance of having been partly swept away.

The General Scene – Extent of Damage

Harrisburg is now perfectly isolated, the waters having rushed over the banks of the river about four miles above, forcing a connection with the Paxton Creek. This has greatly increased the volume of water to the north and east. It is twnty feet deep at the Half-Way House, two miles east of the town. It has now reached Vine Street, covering it to the depth of several feet.

On Front Street it is very near the mansion of Sion Cameron. On Second, it has nearly reached Meadow Lane. The canal is completely obliterated in the flood. The gas house is submerged and the supply of gas has been stopped. All the engines in the Novelty Iron Works are under water. Porches, stoops and articles are floating in every direction. Every rolling mill and iron manufactory has been stopped. Over four hundred families are drowned out of house and home.

One million dollars will not cover the damage in Harrisburg alone.

The Damage Elsewhere

The loss of property elsewhere along the banks of the river must be unprecedented. A Rebel invasion, followed by burning and pillage, could not prove as destructive as this flood. Booms on the north and west branches of the Susquehanna have broken, and companies and individuals have lost thousands of dollars worth of logs and timber. Bridges have been swept away, among them the bridge over the Juniata at the Junction, the one over the Susquehanna at Clark’s Ferry; one at Duncan, spanning a creek, while all the rest are more or less damaged. Islands are under water, stock drowned, and household articles lost.

At Middletown the water has flooded a great part of the town destroying a very large amount of property while in fact, all along the stream houses and towns are immersed.

Telegraph communication has almost entirely ceased. The Western Union will lose about $20,000; the United States Company about $10,000; while all the other companies lose heavily.

The railroad communications are nearly all severed. On the Pennsylvania Road, between this and Middletown, the water is ten feet deep in some places, and about Columbia it is deeper. Several bridges, it is through, have been swept away here. The Northern Central cannot cross the bridge here, and are ending their passengers to Baltimore by way of Philadelphia and Reading and cetera. The Pennsylvania Company is running its cars on the Reading Road. Colonel Thomas A. Scott is here superintending the transportation business. The Cumberland Valley Company have ceased running. So also the dauphin and Susquehanna. A large number of strangers are here awaiting transportation.

———————————

News articles are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

;

;

Comments