Ten Questions to Ask at Historic Sites

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 16, 2014

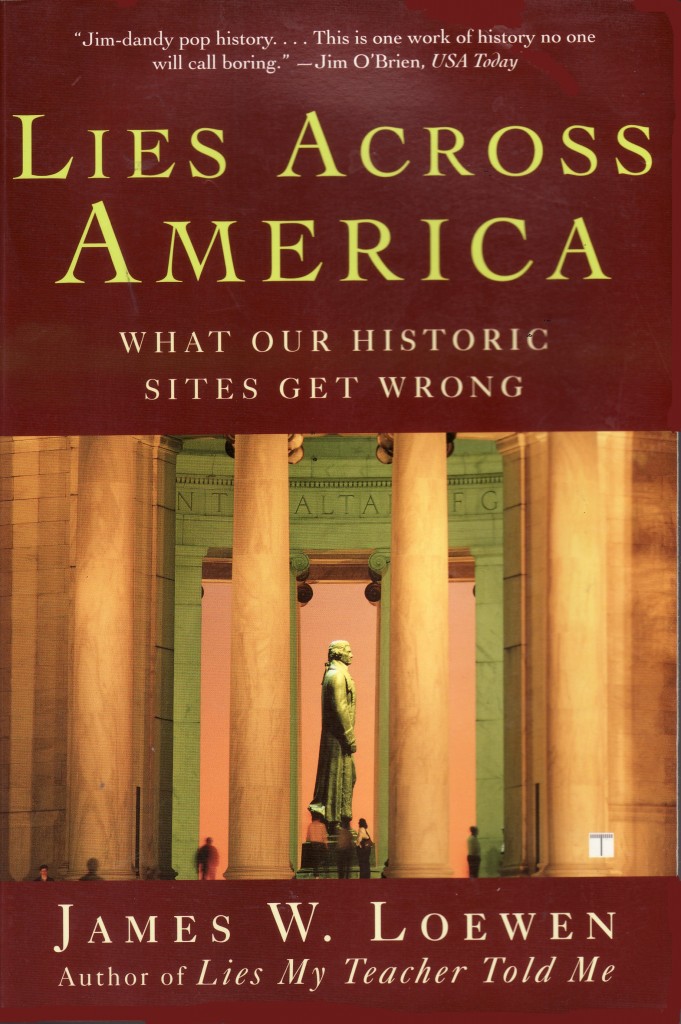

Lies Across America -What Our Historical Sites Get Wrong, by James W. Loewen, published in 1999, is the sequel to Lies My Teacher Told Me. In it, Loewen takes up from the historical distortions he revealed in the first book and shows how these distortions have manifested themselves in the “landscape” in the form of monuments and markers placed at historic sites. In his concluding remarks, he presents ten questions to ask at historic sites – questions which are based on the underlying thesis he develops in the book.

The dust-jacket descriptions states:

In Lies Across America, James W. Loewen continues his mission, begun in the award-winning Lies My Teacher Told Me, of overturning the myths and misinformation that too often pass for American history. This is a one-of-a-kind examination of sites all over the country where history is literally written on the landscape, including historical markers, monuments, historic houses, forts and ships. [Entries are] drawn from each of the fifty states….

Historical “sites” is a catch-all word used by Loewen to describe any public display of history – from an actual historical site complete with markers, monuments, brochures, etc., to a statue or memorial in a park or other public place, to a historic house or building that may have served some interesting past purpose, to a museum dedicated to the history of a particular person, place or thing, etc.

Some important points made by Loewen in the introduction include the categories by which he believes sites should be examined, elements of which are summarized below:

1. Racism– particularly white domination or supremacy, is often evident at the site – with Native American and African Americans often given passive or less important positions – or completely ignored altogether. This category could be broadened to include sexism.

2. Commemoration and Memorialization – there is a difference between recognizing an event that should not be forgotten and heroifying those who participated in it who should instead be reviled or vilified.

3. Omission – the tendency to avoid negative or controversial facts – or people (as well as groups of people) who are not in the power structure when the site (or monument or marker) was created.

4. Overemphasis – the opposite of omission, which gives undue treatment to those in the power structure at the creation of the site (or monument or marker).

The above points, and others made by Loewen in the introduction, serve as a framework for judging the more than 100 historical sites from all fifty states which he has selected to to show “what is wrong” about how history is presented in the American landscape. Where the sites “get it right” is also noted.

For a study of the Civil War, the work by Loewen is particularly helpful in that many of the sites memorialize (or make heroes of) persons who took up arms against the United States, who strongly supported the institution of slavery, and/or continued the fight long after the war was over (e.g., segregationists, post-war versions of the Ku Klux Klan, etc.). These sites are not only in the South, but are found throughout the country. Often, the language used at the site excuses the negative and destructive behavior of the historical participants. By overt and covert racism, by memorializing those who should be reviled, by omitting voices and perspectives, and by overemphasizing one group or person at the expense of others, the sites perpetuate lies about our past and have an influence on the present and future.

It is the hope of Loewen that new research, prompted by questions raised by him in his introduction, will result in other “voices” and “perspectives” coming to the fore and the “toppling” of the most offensive monuments and markers on the “landscape.” The issue of “toppling” is thoroughly discussed in Appendix C – where Loewen identifies twenty candidates for “toppling”, among them monuments and memorials to John C. Calhoun, the Ku Klux Klan (and its founder Nathan Bedford Forrest), and Henry Wirz, the notorious commander of Andersonville, who was the only person executed by the United States for his role in the Civil War. Where monuments and memorials cannot be “toppled”, as in the case of Stone Mountain, Loewen states:

It would be a considerable achievement to vandalize Stone Mountain let alone topple it. Surely however, those who run it can find a way to tell every visitor about the connections between the Confederacy and all three incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan. This more complete history of Stone Mountain, whether told on new historical markers, in a brochure, or by guides, would help visitors realize the past power of the Klan in American life.

For those offended or disturbed by the suggestion that any public monument or marker should be vandalized, Loewen points out that Americans cheered when Eastern European monuments were toppled (and also in the case of monuments in Iraq, occurring after the publication of this book) and that he uses the word “toppling” (in quotation marks) as a “shorthand for the kind of civic discourse” that results in positive changes in the way public history is publicly presented. Sometimes, as what he suggests take place at Stone Mountain, the “toppling” does not result or cannot result in the physical removal of the memorial, but in a more balanced interpretation of it.

All of this has to do with Loewen’s view of the role of history in our public conscientiousness – a view now more widely held that when he wrote the book (1999) – but still not accepted by many. The way forward in our diverse society is to include those voices and perspectives which have been ignored and to correct misinterpretations and outright lies that are promoted and perpetuated in our historic sites.

In Appendix B, James W. Loewen presents the ten questions that should be asked at a historic site. The ten questions will not be repeated in this blog post (the book is readily available in most libraries and book stores). Instead, they can be summarized as the “who, what, when, where, and why” of historical analysis. They include determining the actual sponsors, the motives and needs of the sponsors, and the historical sources that document the site. The questions are rooted in the four important points summarized at the top of this post – racism, commemoration and memorialization, omission and overemphasis.

The “dust-jacket” description concludes with the following:

Lies across America is a reality check for anyone who has ever sought to learn about America through the nation’s public sites and markers. Entertaining and enlightening, it is destined to change the way American readers see their country.

This book should be part of the basic library of anyone involved in public history.

;

;

Comments