On the March: 50th PA at the Battle of South Mountain

Posted By Jake Wynn on February 11, 2013

Background

My post yesterday briefly discussed the occupation of the city of Frederick, Maryland by Union forces during mid-September 1862. As Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia moved westward to execute its movements in places like Hagerstown and Harpers Ferry, the Union army began to make chase. Union commander George McClellan sought to defeat Lee’s army while it remained piecemeal, scattered throughout western Maryland and Virginia. Between the two armies lay South Mountain, a steep, rocky ridge that rose hundreds of feet above the surrounding farmland.

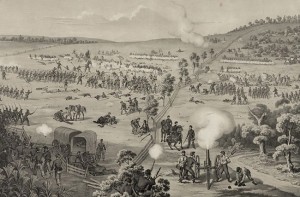

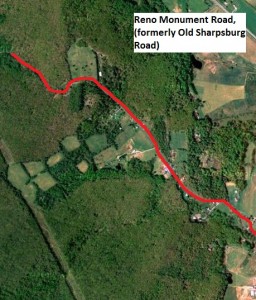

Several roads snake through gaps in the mountain. This is where Lee decided to make an attempt to prevent the Union army from breaking through into the valley beyond. Special Orders 191, dictated by Lee earlier in September, meant that his army was spread across a wide area and highly vulnerable. In this effort, Confederate troops would defend 3 strategic gaps in South Mountain. Turner’s Gap, through which the National Road winded across South Mountain, was the furthest gap to the north. Fox’s Gap, home to the Old Sharpsburg Road, is about a mile south of Turner’s. The third, Crampton’s Gap, lies about 6 miles further south. If a decisive victory could be achieved by the Union army, then complete destruction of Lee’s army could be at hand. September 14, 1862 would be a day for much potential and risk, but in battle the larger strokes of strategy conducted by great generals can be outdone by lowliest of men. It would mark a day of death and destruction, but also of heroics that would rival any of that during the Civil War.

The 50th was camped near Middletown on the night of September 13, 1862, about 4 miles from South Mountain. On the morning of Sunday, the 14th, the Pennsylvania men would begin preparations to march westward towards the slope.

Above them stood the towering Lamb’s Knoll at 1,758 feet. The men of the IX Corps, under the leadership of General Jesse Reno, were marched up the Old Sharpsburg Road, towards Fox’s Gap. Although you cannot tell today, the slopes of Fox’s Gap were largely clear at the time, either from agriculture or logging. It is likely that the men streaming up towards Fox’s Gap could see what was awaiting them at the summit. Several regiments from North Carolina and a Confederate battery commanded the top of the mountain. As the men of the IX Corps began to march up the slopes, the battery opened up and sent shells screaming through the brisk morning air. The long, exposed climb would have shattered more than a few nerves, as Lt. Samuel K. Schwenk of the 50th observed that they “marched forward under fire of shell and grape and canister.” Charles Brown, a corporal in Company C, noted that “All of the Rebel batteries were directing their fire on the road.” If the climb were not enough, the consistent pounding of artillery in their front were to make the first few moments on the battlefield quite miserable.

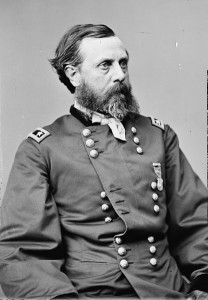

Ahead of them, a nasty scrape had already begun with Ohio men from the General Jacob Cox’s Kanawha Division. They were beaten back, and the men of Colonel Benjamin Christ‘s brigade, including the 50th, 28th Massachusetts, 79th New York and the rookie 17th Michigan stepped forward next. They were initially charged with defending a battery which had become the focus of Confederate fire. Christ utilized the 79th New York and 17th Michigan to stabilize the lines and stave off disaster.

Colonel Benjamin Christ

The next stage of the battle saw the 50th’s fellow brigade units in the thick of battle. The IX Corps began a full scale assault against the top of the mountain. Christ’s brigade was focused primarily on the area directly around the Sharpsburg Road, in the area around a homestead of a farmer named Daniel Wise. The 17th Michigan, the rookie regiment, took the brunt of the action but forced the Confederates back from their perch behind a stone wall. Of their effort, Corporal Brown said, “They had never been in action before, and they came right up the road. I believe the rebels killed half of them before they got to the top of the mountain. The balance of this regiment was brave and they went for the rebels and drove them off the top.” The 17th Michigan attained the nickname of “Stonewall Regiment” from their heroic and deadly work in Fox’s Gap.

But as the fighting continued in and around Fox’s Gap, the 50th Pennsylvania was not among its fellow regiments. It is absent from the after action reports of the attack not because of some mistake, but because they were needed elsewhere. General Orlando Wilcox, commander of the First Division of the IX Corps, ordered the 50th Pennsylvania and the 8th Michigan to assist General Cox in holding the flank. They were deemed to more valuable in holding the Union lines together, as they had already been tested in battle. So as the battle raged to their right, the 50th lie in wait in case of a sudden and unexpected Confederate counterattack which never fully materialized. The 50th fired several volleys into a half-hearted attempt to turn the Union flank, and succeeded in brushing off the blow.

While a few men were wounded in the battle, only one, Private Partial Kennedy of Co. K, would later succumb to his wounds in a Frederick hospital in October.

The 50th held up well under fire and proved its worth as good as “two ordinary regiments.” Having its first real baptism of fire a few weeks earlier at Second Manassas, the regiment was given the good fortune of holding a far flank which never faced a serious threat. Had they been in the thick of things, alongside the 17th Michigan perhaps, then their mettle would have surely been tested. But as it were, the regiment survived to face an even larger battle only a few days later along the banks of the Antietam Creek.

Notes:

A great read on this subject is a book titled: Our Boys Did Nobly: Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, Soldiers at the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam by Antietam Park Ranger and historian John Hoptak. He is also the author of a book that covers the Battle of South Mountain from a wider perspective titled The Battle of South Mountain. His blog about the 48th Pennsylvania is also a great read and can be found at http://48thpennsylvania.blogspot.com/.

Other posts on regiments from the Lykens Valley area during the Battle of South Mountain are coming soon! In the next few weeks I hope to cover several more units during the critical, yet overshadowed battle that preceded Antietam.

;

;

Comments