Michael Haverstick – Died at Chattanooga in 1864 – The Care of War Orphans

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 26, 2013

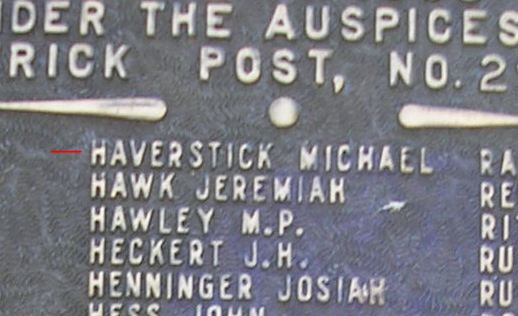

The name of Michael Haverstick appears on the Millersburg Soldier Monument. Haverstick served in the 16th U.S. Infantry Regiment of the Regular Army, Company H, as a Private. He was mustered into service on 25 February 1864, at York County, Pennsylvania. At the time of his enrollment, he was 43 years old, was a miller by occupation, had gray eyes, black hair, a sandy complexion, and stood 5 foot, 9 inches tall. According to the history of the regiment, it was moving toward the Atlanta Campaign at the time Michael Haverstick joined them. However, he got never got to participate in that campaign as he died of disease at Chattanooga, Tennessee, on 21 May 1864, and was buried in the cemetery there.

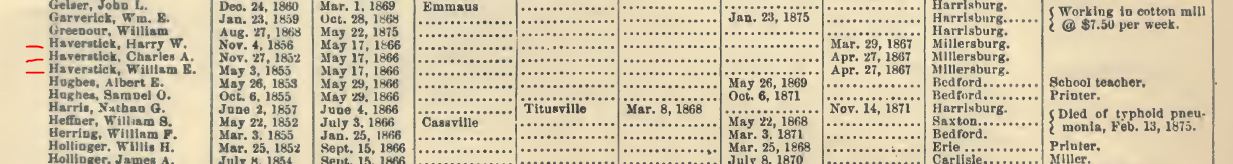

His death presented a problem for his widow, Susan [Meyers] Haverstick, who was faced with raising several young children now on her own in Millersburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Three of those children were sons, Charles Haverstick, who was born 27 November 1852, Williard E. Haverstick, born 3 May 1855, and Harry Haverstick, born 4 November 1856. She applied for a pension on 3 September 1864, which she eventually received. Although the pension was based on the number of minor children she had to support, it must have been very difficult for Susan to deal with all the obligations of raising a large family without the presence of a husband in the home.

In 1862, Gov. Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania began to explore the possibility of having the government care for the war orphans. The Pennsylvania Railroad had offered a generous contribution of $50,000 which was supposed to go to help pay to raise and outfit Pennsylvania troops. At the time, Curtin refused the donation, because he believed that the Pennsylvania legislature needed to approve accepting it, so, at the time, the offer was put on hold. By 1864, with the increasing number of war orphans resulting from soldier deaths, Curtin decided to push the legislature to action. Curtin’s plan was to establish a number of orphans’ schools throughout the state and take on the responsibility for properly raising and educating them. But there was great resistance from the Pennsylania legislature to doing this.

In 1876, a history of the schools that were established was published by Claxton, Remsen and Haffelfinger of Philadelphia. Written by James Laughery Paul, and entitled, Pennsylvania Soldiers’ Orphan Schools, the book gave a detailed history of the establishment and operation of the schools over more than their first decade of existence. The book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive [Note: click on title to go to download page and follow instructions in “View the Book” box at left]. Also included in the book is a complete listing of all the orphans who benefited from the schools (including their birth dates), a history of each of the facilities, and names and titles of the staff members.

Gov. Curtin had a great deal of difficulty in winning over the Pennsylvania legislature. As explained in Pennsylvania Soldiers’ Orphan Schools, page 150-151:

When in 1864, it was first proposed that the State assume the care and education of all the children whom the war had made necessitous, a decided majority in the House of Representatives… was opposed to the measure. The war had increased the public indebtedness, and the project, though humane and worthy, would, if carried out, require large sums of money during at least the next decade; and hence legislators hesitated to fasten upon the Commonwealth this additional burden. But the people who fought the battles and uncomplainingly bore the expenses of the war, were no less willing to recognize and discharge their obligations to a deserving and numerous class of unfortunates of whom its cruelties had robbed of the means of natural support. As the grand scheme of beneficence became known and its objects understood, it gathered strength and made friends. Its advocates were confined to no party creed. The wisest statesmen were it warmest advocates. And yet there have not been wanting those who, during all the years of its history, have seemed to look suspiciously upon the great work and to grudge the means required for its continuance. The disposition to contract rather than to expand the State’s liberality to the orphans has too often manifested itself in the halls of legislation.

In resisting the narrowing and belittling of the undertaking, while no set of men can claim the exclusive honor, the soldiers of the late war may justly demand a preeminence. Especially is this true of the Grand Army of the Republic [G.A.R.], an organization composed of the honorably discharged veterans of the war for the suppression of the rebellion. To perpetuate the remembrances of that struggle, to keep alive the friendships which were formed amid common hardships and dangers, and to cherish a love for the Union of the respective States for which they fought and bled, are some of the objects of its existence. And among other obligations of mercy, the members of this brotherhood are pledged to extend air, when necessary, to the unfortunate families of their comrades who were slain and crippled in battle. Fidelity to their vows, quickened by a remembrance of the dead and a regard for the living, have placed these banded warriors foremost in the support of that system which provides a home and a school for those whom they are obligated to defend and protect…. Not only has the Grand Army ever been ready to exert its powerful influence in favor of securing ample appropriations for the support of the schools, but it has also heartily favored every enlargement of the State’s liberality to the orphans.

It is largely due to its influence that provisions have been made to aid the pupils, after completing their terms at the schools, to continue their studies at the normal schools of the State…. With a little more assistance, many could be fitted for a career of highest usefulness as teachers. Deeply impressed with this fact, the members of this organization deemed it a duty to see that some provision was made for this class of orphans….

Curtin was able to convince the Pennsylvania Railroad to use the $50,000 donation that they were willing to make for the raising and outfitting of troops to be channeled into the orphans project – which the legislature gratefully accepted. Thus began the system of orphans’ schools, of which the State of Pennsylvania became a national model.

By 1866, there were a total of 1135 younger boys and girls and another 1551 older boys and girls residing in state orphans’ schools. These schools were located throughout the State, and in Philadelphia, a special home for “destitute colored children” was established.

Thus, the benefits to the children of Michael Haverstick should be noted. Charles, Williard and Harry, were pupils at the school at Paradise, Lancaster County from 1864 to 1866 and at White Hall, Cumberland County, from 1866 to 1867. A portion of the orphans list from each of the schools where they resided is shown below [Note: click on document to enlarge].

The White Hall School was located near the White Hall railroad station in Camp Hill, Cumberland County, about 3 miles west of Harrisburg.

The re-location of the Haverstick boys to the Cumberland County home from the Lancaster County home was probably so they could be closer to their families for the purpose of visiting. There is no picture of the Paradise home and school in the above-mentioned history, but there is a picture of the White Hall home and school:

Each of the State homes was built on a plot of land of about 3 acres, allowing for outdoor recreational activities on its campus.

It is not known how successful the systems of soldiers’ orphan homes was in Pennsylvania as there are no comprehensive studies that have been done which analyze the records of every orphan who participated. In the case of the Haverstick sons, one biographical sketch has been located for Harry W. Haverstick, which appeared in the Commemorative Biographical Encyclopedia of Dauphin County, page 1157:

Harry W. Haverstick, railroad agent, was born in Duncannon, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 4 November 1856, son of Michael Haverstick and Susan [Meyers] Haverstick. Michael Haverstick was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a miller and settled in Perry County in 1853. He enlisted in 1864 in the Sixteenth United States Infantry. He died at Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1864, from disease contracted in the army. His wife, Susan Meyers, was also a native of Cumberland County. They had eleven children; seven are now living, of whom Harry W. Haverstick is the fifth.

After the death of his father, Harry W. Haverstick removed, with his mother, to Millersburg, where he was educated. He attended the public schools and was a pupil of the Soldiers’ Orphans’ Schools, of Paradise, Lancaster County, and White Hall, Cumberland County; in the latter, he was the first student entered.

In 1871, he engaged with the Northern Central Railway as clerk in Millersburg, was promoted in 1881 to ticket and freight agent, and has filled that position ever since.

Mr. Haverstick has been notary public in Lykens since 1891. He was formerly a stockholder and director in the Lykens Bank. He is president of the school board of Lykens for the third term. He is a Republican, and a member of Wiconisco Lodge, I.O.O.F.

Mr. Haverstick was married, in 1878, to Miss Elizabeth Schreiber, daughter of Benjamin Schreiber, of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. Their children are: Edna L. Haverstick; A. Mildred Haverstick; and Park W. Haverstick. The family attend the Methodist Episcopal Church.

——————————

The complete widow’s pension application file for Susan [Meyers] Haverstick consists of 60 pages of documents which are available through Fold3.

;

;

Comments