Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania – Selections from a 1945 School Textbook

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on July 9, 2012

Herbert E. Stover‘s Pennsylvania: A History of Our State was a textbook in use in the schools in the Lykens Valley area in 1945 and for some years afterward. The well-used copy belonging to the Gratz Historical Society is shown above and now resides in a large collection of texts that were in use in one-room schoolhouses in the region, with this specific copy from the Lower Mahanoy Township Schools. Old textbooks help to understand what was taught to young people at specific periods in history.

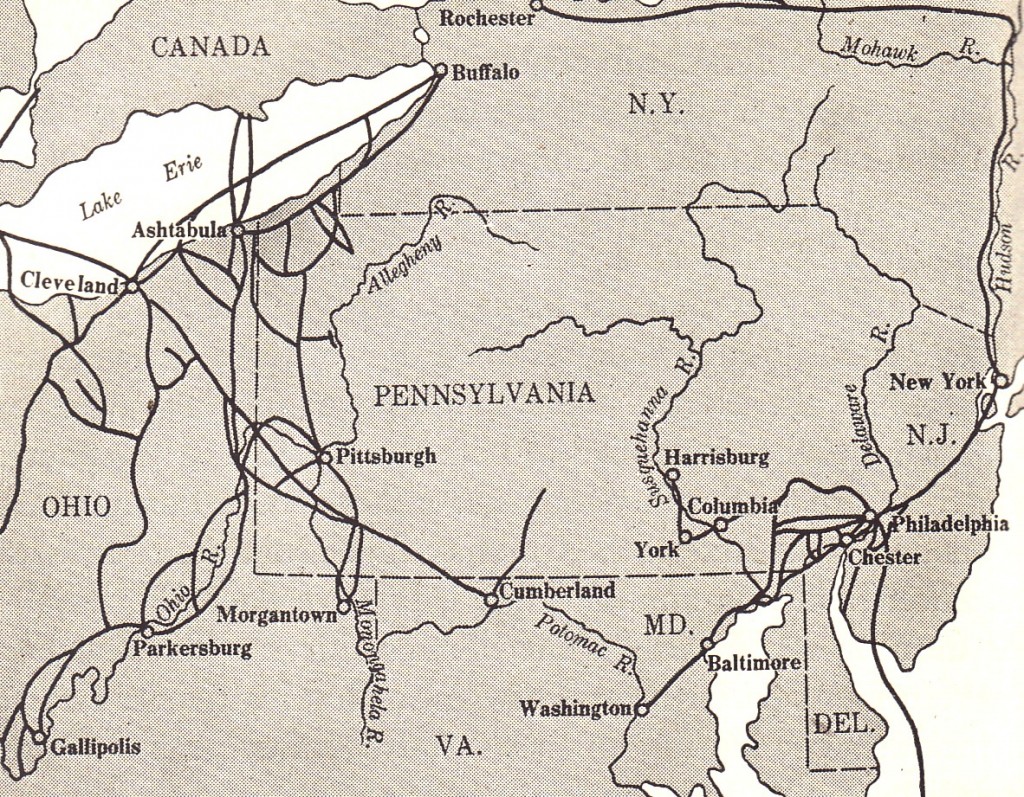

In the chapter on “The Slavery Question,” the author expounds on the “Underground Railroad” and the role Pennsylvania played in ending slavery. Particularly pertinent to the Lykens Valley area were references to the Susquehanna River Valley. Portions of the text are re-printed below, along with the map which shows the routes taken in the quest for safety and freedom. While the routes on the map seem to have a northern terminus at Harrisburg, all of the towns along the river on the way to Williamsport, Lycoming County, served as “stations” of the “Underground Railroad.”

The “Underground Railroad“

Ever since the formation of the Union, Pennsylvania had shown a strong disposition to take matters into its own hands when it felt that its liberties were threatened…. It now asserted what it regarded its right to help the victims of an unrighteous law [Fugitive Slave Act]….

Negroes in the border states were being sold to operators of cotton plantation in the “deep South.” Prices had risen to the point where a good field hand might bring as much as $2000. The phrase “sold downriver” struck terror to the hearts of the border [state] Negroes. Many accordingly seized the first opportunity to “follow the North Star”; that is, they went north, traveling at night and hiding by day.

Three hundred miles of Pennsylvania’s border beckoned to such potential fugitives, since they knew that there were many people in the state who were prepared to offer them food and shelter and to start them off again on their way. So many slaves escaped in this manner that a Southerner exclaimed, “There must be a railroad!” Thus originated the expression, “Underground Railroad.”

The town of Columbia lies on the lower Susquehanna, opposite Wrightsville, where the river is wide and where a ferry long operated in the early days. Thither fled the members of the Continental Congress after the British took Philadelphia. Wrightsville was actually favored as a site for the national capital. This historic spot was now a stopping place of fugitive Negroes. The grandson of the original ferryman, William Wright, was an abolitionist and did everything in his power to aid the runaways. He is said to have been the first to suggest the establishment of “stations” on the “underground” route. According to this plan, one person would care for a refugee for a day or two and then pass him on to the next “station,” and so on until he reached a place of permanent safety. cellars, attics, haymows, and the like were used to conceal runaways as a precaution in case of raids by officers of the law….

Most of the slaves entering the state came by way of Chester, where the Quakers were known to be especially solicitous for their welfare. Citizens of Chester operated in the South, helping Negroes to escape and giving them instructions for the journey. A Negro woman named Harriet Tubman made many such trips, guiding fugitives along the devious “underground” route into Chester, where the Quakers financed her work. She became known as “the Moses of her people.”

Thomas Garrett, a Pennsylvanian, removed to Wilmington, Delaware, aiding some twenty-seven hundred Negro people from that state to reach the North. As a result of his defiance of the Fugitive Slate Law, his life was repeatedly threatened, and all his property was ultimately consumed in the payment of fines….

An Ohio Quaker named Levi Coffin, with the co-operation of his wife, enabled one hundred fugitives a year, on an average, to attain their freedom…. On one occasion this man hid seventeen runaway slaves. He was arrested, taken before a magistrate, and then interrogated before a grand jury. when asked whether he had shielded fugitive slaves, he replied that seventeen homeless persons had come to him and that he had merely obeyed the Biblical injunction and “taken them in….” He was acquitted.

Carlisle likewise maintained an active station. Two men from Maryland once appeared in the town in search of escaped slaves. A riot ensued, in the course of which one of them was so severely beaten that he died from his injuries.

Most of the towns along the Susquehanna served as “underground” stations. At the Wallis place, near Halls, a subterranean passageway led from the cellar to the near-by river, well screened with vines and bushes.

At Williamsport, a quarter of a mile from the end of Market Street, stood a log structure, in a dense grove of pines and hemlocks, which served as a station both before and during the Civil War. There Negroes were fed and housed by free colored people and by descendants of indentured whites….

Some of the work of the “underground” was performed… by those who merely loved adventure. It was fascinating to match wits with the law and the slave-hunter…. But behind the movement there was something deeper. Northerners entertained scant sympathy for slavery. They had long since freed their own slaves and had been extremely patient with the perpetuation of the institution in the South. Now they were resolved that it should go. When the first fugitive negro, utterly spent, staggered across the threshold of a Quaker home near the Pennsylvania line, involuntary servitude in the United States was doubtless already doomed!

The map and selections above were taken from the Stover text previously mentioned which was published in 1945 by Ginn and Company of Boston. Herbert E. Stover was the Supervising Principal of the Lewisburg Public Schools. For previous blog articles on the Underground Railroad, click here.

;

;

[…] Image source: civilwar.gratzpa.org […]