William Withers Jr. – Lincoln Assassination Witness – Resources for Study

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on June 23, 2012

This post continues the examination of Lincoln Assassination witness William Withers Jr. by reviewing some of the available resources for the study of his life, his role at Ford’s Theatre on the night of 14 April 1865, and his exaggerated telling of that story. The prior posts on this blog were entitled William Withers Jr – Lincoln Assassination Witness and Testimony of William Withers Jr. – Lincoln Assassination Witness. Withers is connected to the mission of this blog because of his association with a Pennsylvania regiment during the Civil War as well as his documented later performances in Dauphin County. Although there is no evidence that he ever lived in Pennsylvania or Dauphin County, there is evidence that he used his experiences in the Pennsylvania regiment (as a musician) to claim a pension as an invalid for his Civil War service, and according to National Archives documents, the service in that Pennsylvania regiment was the sole basis of his claim.

One assassination writer to devote several pages to Withers was Louis J. Weichman. In his book, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspirpracy of 1865 (New York: Knopf, 1975), Weichman reports that Withers was the “one” obstruction that Booth “encountered” in escaping from the theatre. He then explained why Withers was standing near the stage door, told of an earlier encounter Withers had with Booth “in front of a saloon,” and described messages that were exchanged between Withers and the stage manager regarding the playing of the song “Honor to Our Soldiers.” Weichman also created a conversation between Edmund Spangler and Withers that involved the reasons that Withers was back stage and told of Withers sitting on the lid of the box that controlled the theatre lights to “spoil” Spangler’s plan of having the house lights shut off. Weichman then concluded the story of Withers with the following encounter between Withers and Booth:

Mr. Withers was about to return to the orchestra when the crack of a revolver startled him. All was quiet instantly, and then he saw a man jump from the President’s box to the stage. It was Booth. He ran directly to the door leading into the alley. This course brought him right into the path of Mr. Withers. He had a dagger in his hand and waved it threateningly. He evidently did not recognize Mr. Withers, for he appeared like a maniac. His eyes seemed startling from their sockets and his hair was disheveled.

With head down, he ran toward Mr. Withers and cried, “Let me pass!” He slashed at him and cut through his coat, vest, and underclothing. The assassin struck again, the point of the weapon penetrating the back of Mr. Withers’ neck, and the blow brought him to the floor. Withers saw him make his exit into the alley and caught sight of the horse held by Peanuts John.[page 152-154].

On what did Weichman base his story of Withers? Only one end note covers the above pages and that end note references Pitman, previously mentioned on this blog as one of the available transcript versions of the trial of the conspirators. From prior examination of Withers’ trial testimony (see Testimony of William Withers Jr. – Lincoln Assassination Witness) it is known that Withers declared under oath that he neither saw Booth nor Spangler “that day”.

One of the most complete of the exaggerated versions of the way Withers came to tell his story of what happened at the theatre that night was published in Broadway Magazine, in May 1904. Fortunately, this article is available as a free download (click here – Note: download Volume XIII, Google Books, Hampton Magazine, and the article appears beginning on page 117).

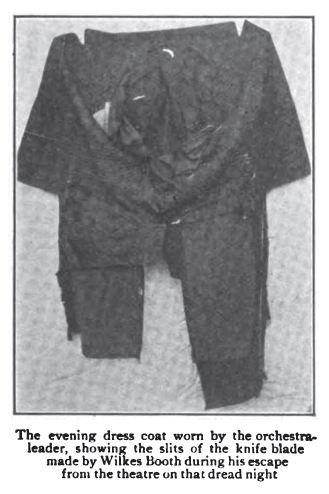

As can be seen from the “Table of Contents” (above), the article about Withers bore no author’s name and was entitled “The Man Who Saw Lincoln Shot: The Thrilling Truth For the First time Told by a Living Eye-Witness, William Withers, Jr., Orchestra-Leader of Ford’s Theatre on the Fatal Night, April 14, 1865.” If the article was written by Withers, it was not published in the first person. Included in the article are fairly good reproductions of several pictures – Abraham Lincoln, a portrait of Withers under his own vine and fig tree with his pets and Stradivarius violin, the playbill from Our American Cousin which contained the words to “Honor to Our Soldiers,” and the dress coat that Withers wore as orchestra leader which supposedly shows the slits made by Booth’s dagger. The article clearly states that Withers encountered Spangler near the machine that controlled the house lights but does not tell the story that Withers and Booth had met earlier in the day for a drink. Of interest is Withers claim that he saw a “flash of light” and heard the pistol shot which was followed by silence. Then Withers tells what happened next, including the words supposedly spoken by Booth:

Wilkes Booth, the picture of fury, rage and despair incarnate, plunged into the passage. What a transformation! He seemed to heed nothing, struggling painfully with a broken leg… and came forward, slashing blindly right and left, his eyes glinting the fires of madness, his hair dishevelled, his coat torn and awry.

“Out of the way!” he shrieked. “Let me pass, or I’ll kill, kill!” bending forward with lowering head like an infuriate bull, swinging his dagger here and there through the now darksome passage like one blind. His very first blow caught Withers in the back of the neck, the second thrust landing just under the right shoulder blade. It felled the victim to the floor.

Booth stooped over the prostrate form and for the instant seemed to recognize his old friend, who was unwittingly the first to obstruct the assassin’s flight to safety. “God, Billy Withers!” he cried hoarsely, made a flying leap and struck straightway through the terrified ranks of the stage hands to the rear. On this desperate retreat he went out of his way so far as to reach for the gas-governor to shut odd the lights; but, alas, for him, he threw the governor around so hard that it broke off short without even dimming the jets. From where Withers lay, stunned and bleeding, he saw Booth bolt for the rear door, open it, and by the street lamp’s glow, saw him dash toward a man in waiting there – a character familiar to them all, and known as “Peanut John.” The latter was holding a saddle horse in readiness.

At this climax of events, Harry Hawke, who was playing the part of Asa Trenchard, came rushing through the passageway. He was in hot pursuit of Booth. Naturally he stumbled and fell headlong over the prostrate form of Withers, “Oh, God; Billy!” he moaned, rolling in the dust. “The President is shot…! ” Then for the first time Withers realized what that flash of light and the accompanying report really meant…. He tried to cry out, but could not make a sound…. For a few moments he utterly lost consciousness; then suddenly half a dozen detectives came stumbling in upon him, thinking that he was the assassin, seized him boldly, and dragged him, faint and bleeding, through the rear door to the street.

An awful scene here met the leader’s gaze. The whole City of Washington seemed to belch forth from every crevice and cranny…. It was a human conflagration. Beholding the blood-bedaubed figure in the detectives’ clutches, they, too, became possessed of the same illusion, they screamed like maniacs, “Hang him! Lynch the d– dog! Lynch him… Ropes… A score of the boldest pressed forward and laid violent hands upon the fainting musician.

“No, no, no!” moaned Withers faintly, struggling with his captors. “You’ve got the wrong man. I am not the assassin. I am Billy Withers, leader of the orchestra.” Does nobody know me. It was not I who killed the President. It was Wilkes Booth — before God it was Wilkes Booth! See, he stabbed me – stabbed me in the dark when I blocked his way. See, see!” and he held up the dripping togs to convince the mob.

But the mob did not wish to be convinced. The mob wanted vengeance — upon anybody, upon anything, so long as it was a blood atonement…. It looked like a foregone conclusion that Withers would be snatched down into the turbulent mass and literally torn limb from limb. Several friends passed near, but none recognize the bedraggled and frightful caricature of a man held there in the detectives’ clutches, and he himself was too weak to cry out above the tumult of the gathering throngs. The detectives were rifling his pockets for incriminating evidence. If he was not the arch-conspirator, he was in league with them, so they thought.

In the midst of these scenes… came deliverance in the person of the Mayor of the City of Washington. He it was who demanded that, guilty or innocent, Withers should be taken into custody to save instant bloodshed. Thus, within a few moments, was the exhausted musician landed finally behind bars, and there fell upon the stone floor of his cell in a dead faint….

It was many hours before Withers was finally identified and release, and he went away, his broadcloth evening dress suit (still preserved), torn to rags. By a hair’s breadth was the musician’s life saved.

The article concluded with the words from two verses and the chorus of “Honor to Our Soldiers,” words which were written by the song-writer H. B. Phillips, not Withers. Withers composed the music. The article does state that Withers’ reason for being back stage was to consult with the stage manager regarding when the song would be performed and this is consistent with Withers’ testimony at the trial of the conspirators.

There are some strange declarations in this article but no more strange than the way Withers would tell the story on many other occasions to anyone who would listen. For example, Withers has Lincoln’s son Tad attending the performance and peering over the box railing and loudly stating that he recognized Withers, with Lincoln following Tad’s gesture with a “good-natured” nod at the orchestra leader. It is also stated that Withers was the orchestra leader during the terms of Presidents Pierce and Buchanan, who when they attended the theatre always acknowledged the audience. Finally, as Our American Cousin progressed, Withers follows Booth’s movements through the theatre – with Withers recognizing such detail as the “beads of sweat glistening among the curling locks along the pallid breadth of his brow” and “he appeared to be in deep thought.”

If this account was intended to be a fictional representation of what happened at Ford’s Theatre that night it certainly was not presented as fiction. Withers himself told almost the exact same story to newsmen – with flair and embellishment – and some of Withers’ accounts pre-date the Broadway Magazine article.

No one has yet written a full biography of Withers although there is the possibility that one writer has gathered enough material to make a decent attempt to do so.

The only article on William Withers Jr. for which it can be said bears some degree of respectability, appeared in American Heritage Magazine, February/March 1991. It was entitled “John Wilkes Booth’s Other Victim,” and was by Richard Sloan. This article is available on-line: click here. The article is also available in a “pay” Google-Books edition: click here.

Sloan has dedicated many years to the study of William Withers Jr. and Jeannie Gourlay (a member of the Our American Cousin cast) and while the full extent of his knowledge does not appear in the American Heritage article, a talk he gave in 1996 at the Pike County Historical Society (Pennsylvania) presented many previously unknown and unpublished materials. That talk was lavishly illustrated with slides which documented nearly everything he stated. Sloan laid out the story of Withers’ life paralleling it with events in the life of Jeannie Gourlay. Many in the audience were surprised to learn that within days after the assassination, and before the trial of the conspirators, Withers married Jeannie Gourlay – and that she later divorced him, marrying Robert Struthers and “retiring” to the small community of Milford in Pike County. Withers, according to Sloan, was talking with Jeannie Gourlay backstage at the moment that Booth was fleeing the theatre – something not publicly stated by Withers in his accounts. After Jeannie divorced him, Withers never re-married. Jeannie Gourlay visited Withers in New York just before he died, and possibly re-claimed a locket she had given to Withers during their engagement. Sloan concluded the talk with some speculation – that Withers was unable to consummate the marriage – but admitted that this was only speculation. He also noted some far-fetched comments by another assassination writer – that Jeannie was pregnant with Withers’ child and they had to get married.

Of course, all that Sloan stated in his Pike County talk in 1996 will have to wait until he decides to publish an article or book based on what he knows and the resources he has accumulated.

The woodcut at the top of this post is from an article that appeared in the Suburbanite Economist, 9 February 1917, “Stabbed by Booth: Theatrical Man Recalls Struggle with Lincoln’s Murderer on Stage at Ford’s” and was found in a GoogleNews search. The picture of Withers’ coat is from the Broadway Magazine article, available via the GoogleBooks download.

The final blog post on William Withers Jr. will appear in about one month and will examine his credibility as an assassination witness. It will include some additional analysis of his military experiences. Prior blog posts on the Lincoln Assassination can be found by clicking on the “Topic” Lincoln Assassination.

;

;

As a relative of his he was there, did see Booth and received a stab wound on hs left side. I have numerous documents about this.

Where is William Withers Jr. buried?

Withers and his brother Reuben are buried in the cemetery in Rye, NY