The Bloody Dress of Laura Keene Arrives in Baltimore

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 5, 2012

The journey of Laura Keene from the stage at Ford’s Theatre on the night of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln to Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, where she was arrested and held by the Provost Marshal, continues in today’s post. The last post on this topic was on 22 February 2012, when her flight from Washington was arranged. To get out of Washington, she had to arrive safely at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station north of the Capitol and board the train – with her entourage – which consisted of actors Harry Hawk and John Dyott – and a large amount of baggage – which included all her clothing, stage and travel items as well as those items belonging to the male actors. This was all arranged by her manager, John Lutz, who was also “posing” as her husband. Lutz had made the arrangements to get Harry Hawk released from jail and had somehow secured passes for the group to travel out of Washington.

How much baggage the group was carrying is a matter of speculation, but biographer Ben Graf Henneke, stated that Laura herself had at least nine trunks:

Lutz saw to it that Laura had the finest matched set of leather luggage family influence could provide…. Laura would have had more [than nine trunks]…. To her luggage she added a piano: one of her indulgences was the purchase of a Chickering upright. The initial cost, if she paid the advertised price was $500. It must have cost her many times that over the years as she had it moved with her from one town to the next. (page 185).

Laura had planned to play her piano to accompany the audience in the singing of “Honor to the Soldiers,” originally to be performed for Gen. Grant who was to be the guest of the Lincoln’s at Ford’s Theatre. But Grant didn’t appear and the play was cut short before the song was sung for Abraham Lincoln and the many soldiers who were attending the performance. The piano was one of Laura’s possessions that Lutz had to arrange to be moved out of the locked theatre. Payment had to be made to the appropriate people to get all of Laura’s possessions to the train station on time for their hoped-for departure.

Lutz also had to arrange to purchase the tickets for the train trip and secure the necessary approvals so the party could leave Washington. Since she was scheduled to appear in Cincinnati on Monday evening, it makes sense that Lutz worked extra hard to get everything completed for the Saturday evening train. If that were not possible, the party could have have left as late as Sunday evening – but that would mean they would not arrive in Cincinnati in time for the Monday performance. All indications are that Laura insisted that the group leave by Saturday night.

The available connections to Cincinnati for the days immediately following the assassination are still being researched. There were several possible routes and all of the routes involved multiple connections over several railroads. The first stage of all these routes was from Washington to Baltimore. There was only one train station in Washington for a northern departure from the city – and that was the Old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station, previously mentioned. One thing that needs to be noted is that virtually no cities had “union” stations – meaning each railroad serving a city had its own train depot, usually in a different part of the city. While different railroads cooperated with each other in coordinating trains for the ease of passengers in making connections, getting from one station to another was the responsibility of the traveler. Tickets had to be purchased on arrival at the station where the next departure would take place, and often when the arriving train was late, the traveler had to wait for the next available train, sometimes not until the next day, so accommodations had to be obtained at one of the hotels near the station.

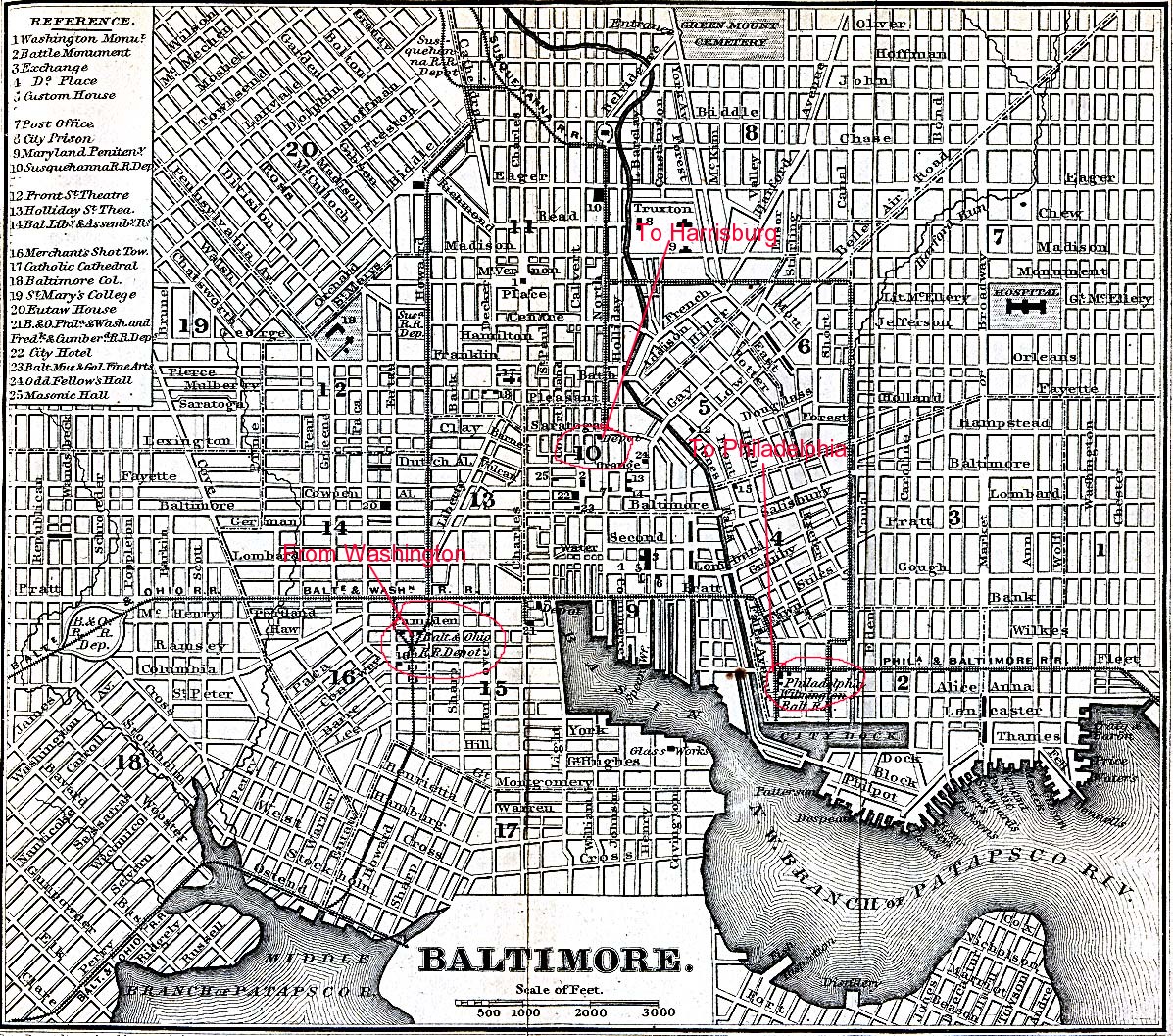

In Baltimore in 1865, there were three major railroad stations – the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Depot (“From Washington” on the above map), Northern Central Railroad (or Susquehanna) Depot (“To Harrisburg” on the above map), and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad Depot (“To Philadelphia” on the above map). A street railway with horse-drawn cars connected these stations. But street railways were not equipped to carry much more than than what the passenger himself/herself could carry, so in Baltimore, John Lutz had the additional task of arranging for transport of Laura’s nine or more trunks, plus her piano, and the baggage of Harry Hawk and John Dyott – all to the next railroad station, where he then made arrangements to purchase the tickets for the group and to have the items loaded into a baggage car on the waiting train.

The unpleasantness of train travel is described by Henneke:

Laura’s troupe was not big enough to fill a single car; therefore she was thrust into cars with others who couldn’t be intimidated by her imperious sniffs at “tobacco!” or be bullied by her fastidious withdrawing of the hems of her garments. Day coaches in America were awash with chewing tobacco spittle. The experienced traveler learned never to put anything under his seat. The men sat either with their feet on the empty chair ahead, or their knees pushed into the back of the chair ahead if it were occupied. Women wrapped their skirts around them and brought boxes or bricks or some object that would lift their feet above high tide…. “No decent person could venture to wade through the stream of saliva floating thereon…. (page 184)

Filth was a commonplace of the times…. Locomotives burned wood or coal and there was a constant shower of sparks, ash, soot, clinkers and dust falling on the cars…. (page 185)

There is no reason to suppose that the train trip on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad from Washington to Baltimore was any different than that described by Henneke. Other writers described similar conditions. If Laura wanted to flee Washington, she had to accept what was available.

For those who believe that Laura Keene cradled Lincoln’s head in her lap in the State Box at Ford’s Theatre, the dress she wore that night – bloodied as it were if the story is to be believed – was in one of the many trunks that John Lutz had to arrange to move out of the city. Laura would not have been wearing a stage costume to travel in. So, the “bloody dress” moved from Washington to Baltimore along with Keene’s traveling group as it fled the city.

The possible description of the dress has been previously noted. While the dress in its entirety has been lost, there are some fabric swatches, supposedly from the “bloody dress,” that have survived, as well as a white, detachable cuff which is currently in the collection of the Smithsonian (Museum of American History). The only known photograph of Laura Keene in what appears to be a dress with white cuffs (perhaps detachable), is shown below. No one knows where or when the photograph was taken – or if the dress remotely resembles the Act III dress from Our American Cousin. Henneke offers the picture in speculation (p. 211).

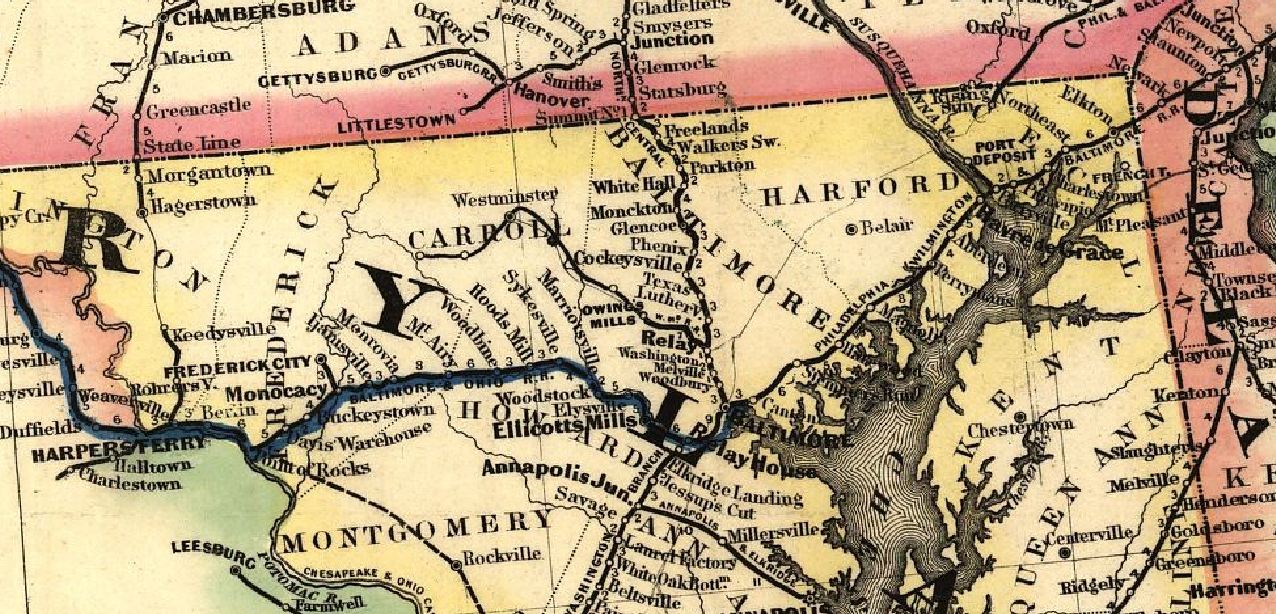

For Laura Keene to get to Cincinnati, Ohio, she had three basic choices in Baltimore: (1) She could travel west from Baltimore via the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, through Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, and thence into Ohio where she would have to make connections to Cincinnati. This is the blue line on the map below. (2) She could travel north and east to Philadelphia where she could then take the Pennsylvania Railroad west to Pittsburgh, and from there, make connections to the Ohio trains to Cincinnati. (3) She could go directly north on the Northern Central Railroad to Harrisburg, where she could make connections with the Pennsylvania Railroad to Pittsburgh, and from there, connections to Cincinnati. This third option had the advantage of arriving and departing at the same station in Harrisburg, which she would not have had in Philadelphia. It it not known why she chose this round-about way, in that the Baltimore and Ohio route appears to be the most direct. It could be that she was leaving her escape options open by taking the route to Harrisburg. By staying on the train at Harrisburg, she did have to option of fleeing to Canada if necessary. There were other choices for more northern routes into Ohio – well out of the way – but she could have traveled to Elmira, New York, and had multiple choices there as well. No one knew the extent of the problems that she would face if John Wilkes Booth was or was not captured. Her arrest and detention at Harrisburg confirmed the uncertainty of the situation – particularly in her case – and underscored the manner in which she fled Washington – with few knowing who got paid off and for what purpose.

The next post in this series will describe the travel from the railroad stations in Baltimore to the railroad station in Harrisburg.

“Keene’s Chickering piano” shown is believed to be her piano (Henneke, page 185) as was displayed at the Chickering Historical Piano Exhibit. The piano was destroyed by fire. The railroad map cut is taken from a map of U.S. railroads at the time of the Civil War. The Baltimore street map was cut from a Civil War-era guidebook whose copyright has expired.

;

;

Laura Keene’s Chickering piano was not lost to fire. It currently is in the Jack Wyatt Museum of the Piano Technicians Guild Foundation. Before we acquired the piano, it was in the East Rochester Museum and before that in the possession of the piano manufacturer who made Chickerings for many decades. It can be seen on page 8 of our website, ptgf,org.

Henneke’s reference to the piano (p. 185, with photo) is based on two sources: (1) Correspondence with E. F. Brooks Jr., president of Chickering & Sons, 1972-1973; and (2) an 11 Apr 1869 letter Laura Keene wrote to an unnamed piano manufacturer in which she said she traveled with her piano. I have seen neither source. Henneke claimed the Chickering president said “whether it was or not [the piano belonging to Laura Keene] … no one could attest.” Henneke then stated: “This piano was destroyed by fire.” No source was given for the latter statement, but it could possibly be assumed that it was the Chickering president who stated it was destroyed by fire.

The same photograph can be found in LOOKING FOR LINCOLN, by Kunhardt, Kunhardt & Kunhardt, p. 179.

There are many different stories on how and when “Honor to Our Soldiers” was to be performed the night of the assassination. Some have Laura singing solo while accompanying herself on her Chickering piano. Other stories have Withers leading the orchestra while the cast sang the song in special costume. Of course, the song was not performed.

If you have the actual piano that was in Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, then it would have had to travel with Laura out of Washington to Baltimore, cross the city of Baltimore to the Northern Central RR Station, and then to Harrisburg – where it would have been removed from the train when she was arrested. Following her release, it then would have been put on the train to Cincinnati.

The piano you have is pictured in color on your website: http://ptgf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/17-Chickering_edited.jpg.

Whether the piano left Washington with Laura Keene or not is not clear to me. Henneke also states on page 212, that “Her piano was locked away in the orchestra pit.” Thomas Bogar in is book Backstage at the Lincoln Assassination writes, “All instruments were impounded after the assassination.” (p. 122) and also, “Lutz arranged for their wardrobe trunks to be carried over from the Metropolitan Hotel and the Evanses, but left behind his wife’s little piano, still in the theatre.” (p. 139) and further that,”…they had to extract their wardrobe, scripts, and instruments from the padlocked Ford’s Theatre. They pleaded for access from Colonel Burnett, who, at Stanton’s order, had carefully logged each backstage item, prop by prop and costume by costume…” (p. 223) Is the listing of Colonel Henry L. Burnett’s inventory known? If the piano is listed there, that would help answer this part of the question. There is also a newspaper article about the piano that can be found online. It is from the Royal Centre Record of May 12, 1966 on page 8. The date of 1966 is not a mistake; this is about the Laura Keene’s heirs donating the piano to Chickering in the early 1960s.

It is also not clear to me whether the piano left Washington with her. If it didn’t leave with her, how and when was it returned to her?

A broader question might be whether there are any 1865 references to Laura Keene’s piano being in Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination?