Leap Year Day, 29 February 1864

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 29, 2012

On 29 February 1864, bad news was received from several war fronts and H. Judson Kilpatrick was leading a secret mission to free Union prisoners being held at Richmond – a mission that would end in total failure.

One “Leap Year” occurred during the Civil War. The extra day was added during 1864 – on 29 February 1864, to be precise. One “Leap Year” occurs during this Sesquicentennial of the Civil War and the extra day is on this current date of 29 February 2012.

Northerners received some bad news in the morning newspapers of 29 February 1864:

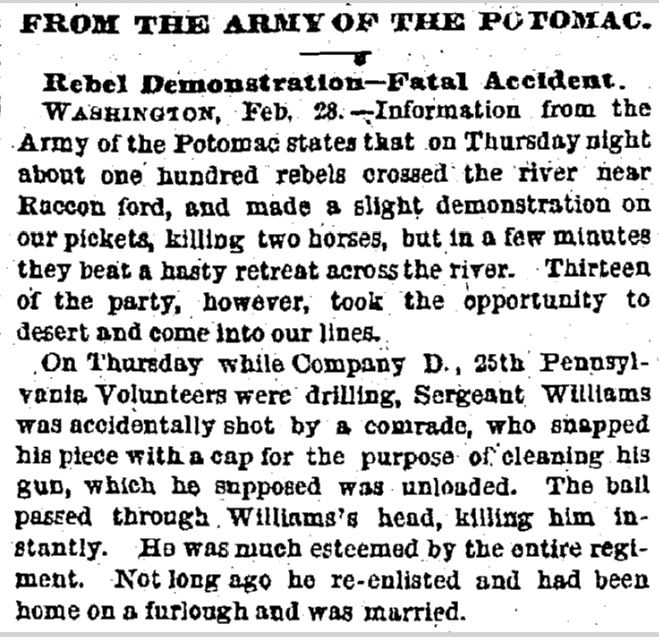

FROM THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

Rebel Demonstrations – Fatal Accident

WASHINGTON, February 28. — Information from the Army of the Potomac states that on Thursday night about one hundred rebels crossed the river near Raccon Ford, and made a slight demonstration on our pickets, killing two horses, but in a few minutes they beat a hasty retreat across the river. Thirteen of the party, however, took the opportunity to desert and come into our lines.

On Thursday while Company D, 25 Pennsylvania Volunteers [sic – should be 26th Pennsylvania Infantry] were drilling, Sergeant Williams was accidentally shot by a comrade, who snapped his piece with a cap for the purpose of cleaning his gun, which he supposed was unloaded. The ball passed through Williams’s head, killing him instantly. He was much esteemed by the entire regiment. Not long ago he re-enlisted and had been home on a furlough and was married.

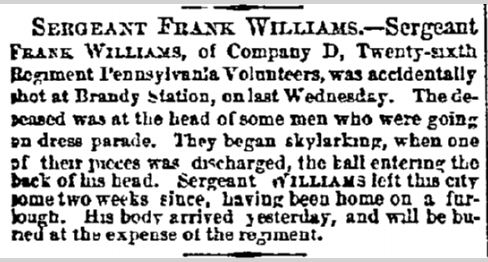

A slightly different version of the story appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

SERGEANT FRANK WILLIAMS. – Sergeant Frank Williams, of Company D, Twenty-sixth regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers [26th Pennsylvania Infantry], was accidentally shot at Brandy Station, on last Wednesday. The deceased was at the head of some men who were going on dress parade. They began skylarking, when one of their pieces was discharged, the ball entering the back of his head. Sergeant Williams left this city some two weeks since, having been home on a furlough. His body arrived yesterday, and will be buried at the expense of the regiment.

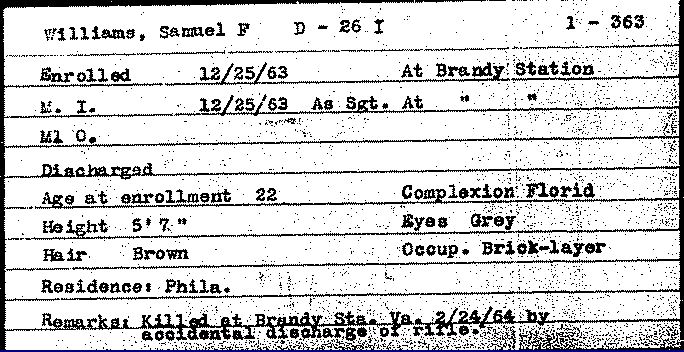

“Frank Williams” was actually Samuel F. Williams, a bricklayer from Philadelphia, as shown by the Pennsylvania Veterans’ File Card:

——————————

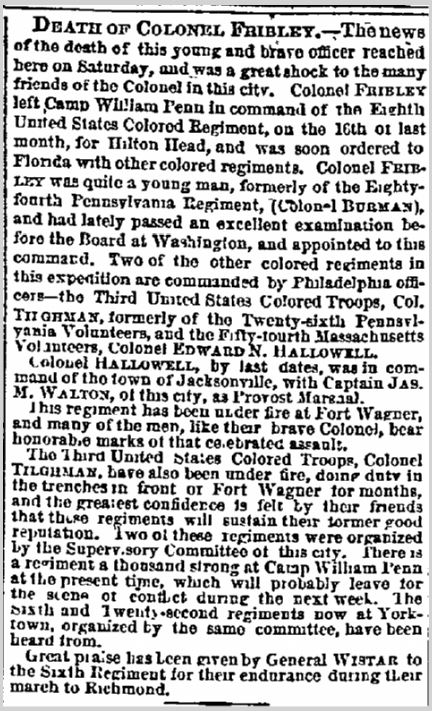

The news was not good from Florida either. Another Pennsylvanian, Charles W. Fribley, who had taken command of the 8th United States Colored Troops, had died:

DEATH OF COLONEL FRIBLEY. — The news of the death of this young and brave officer reached here on Saturday, and was a great shock to the many friends of the Colonel in this city. Colonel Fribley left Camp William Penn in command of the Eighth United States Colored Regiment [8th United States Colored Troops] , on the 16th of last month, for Hilton Head, and was soon ordered to Florida with other colored regiments. Colonel Fribley was quite a young man, formerly of the 84th Pennsylvania Regiment [84th Pennsylvania Infantry], (Colonel Burman), and had lately passed an excellent examination before the Board at Washington, and appointed to this command. Two of the other colored regiments in this expedition are commanded by Philadelphia officers – the Third United States Colored Troops, Col. Tilghman, formerly of the 26th Pennsylvania Volunteers [26th Pennsylvania Infantry], and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, Colonel Edward N. Hallowell.

Colonel Hallowell, by last date, was in command of the town of Jacksonville, with Captain James M. Walton, of this city, as Provost marshal.

This regiment has been under fire at Fort Wagner, and many of the men, like their brave Colonel, bear honorable marks of that celebrated assault.

The Third United States Colored troops, Colonel Tilghman, have also been under fire, doing duty in the trenches in front of Fort Wagner for months, and the greatest confidence is felt by their friends that these regiments will sustain their former good reputation. Two of those regiments were organized by the Supervisory Committee of this City. There is a regiment a thousand strong at camp William Penn at the present time, which will probably leave for the scene of conflict during the next week. The Sixth and Twenty-second regiments now at Yorktown, organized by the same committee, have been heard from.

Great praise has been given by General Wistar to the Sixth regiment for their endurance during their march to Richmond.

Colonel Fribley was Charles W. Fribley, a school teacher from Williamsport, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania (up-river from the Lykens Valley area). In addition to the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company F, in which he had served as Captain, he also had served in the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company A, as a Private, from 24 April 1861 to 1 August 1861. He had begun his service with the 8th United States Colored Troops on 23 November 1863.

——————————–

THE KILPATRICK & DAHLGREN RAID

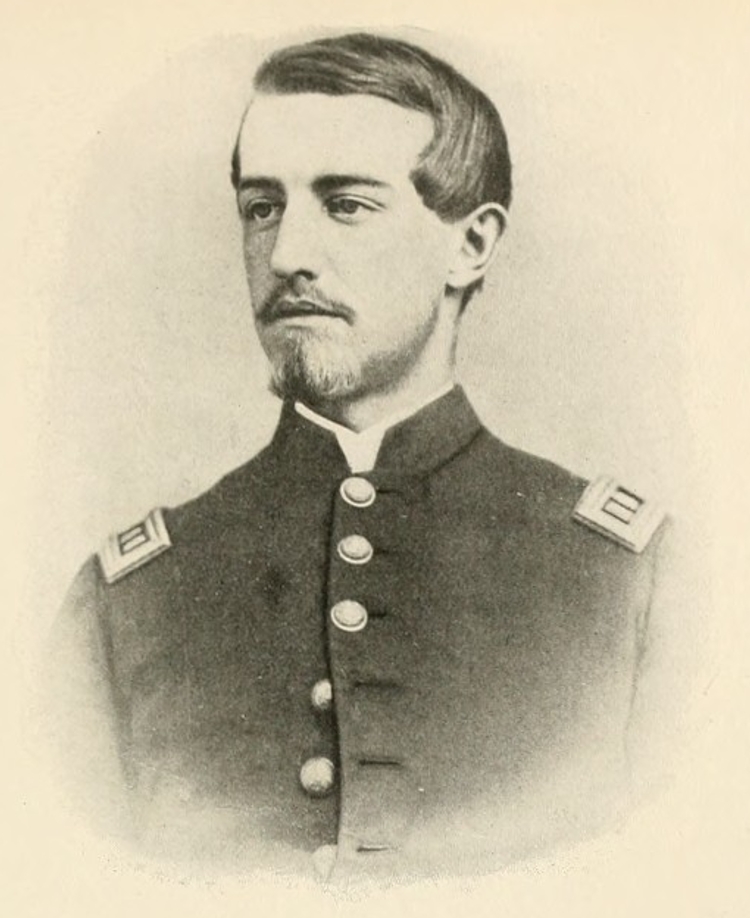

What was not known to the public on this Leap Year Day 1864 was that a mission was underway that involved a great risk to the Union and the men who were on the mission. This was the so-called Kilpatrick and Dalgren Raid which had as its objective a raid into Richmond to free Union soldiers, many of whom were officers, who were held in prison there. This was a very risky endeavor and Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick, who had proposed the raid, was put in charge – because he was the one who had proposed it, and because his general tactics, although successful, were considered reckless by other military men. Gen. Kilpatrick recruited Col. Ulric Dahlgren to assist him in the raid. Dahlgren had lost a leg in Maryland after Gettysburg and was sufficiently healed (and with prosthesis) to undertake the mission. A diversion was planned and conducted by Gen. Armstrong Custer which cleared the path for Kilpatrick and Dahlgren and their men all the way to Spotsylvania Court House, which they reached on Leap Day. The plan of Kilpatrick was to go into Richmond with most of his force from the north while Dahlgren would take the remaining men and approach Richmond from the southwest. By frightening the city into the belief that it was being attacked from multiple sides, Kilpatrick hoped for enough confusion so that he could get in quickly and get the prisoners out. Kilpatrick made good time on his part of the plan despite the bad weather of high winds and sleet. Dahlgren enlisted the aid of a local slave boy to help him find the way in the bad weather, but when the boy led him and his men to an unfordable part of the James River, Dahlgren went into a rage and hung the boy for deceiving him, although many believe that the boy didn’t know the area well enough to be a guide and the visibility was so poor that even the best guide wouldn’t have been able to help. Dahlgren couldn’t get across the river and Kilpatrick, waiting for a signal from Dahlgren, decided to slowly enter Richmond. He was met by an army of resident old men that he mistook for a regular fighting force, so he held back, still waiting for the signal from Dahlgern. When no signal came, Kilpatrick decided to pull back, leaving Dahlgren and his approximately 500 men without defense. Most of them died, including Dahlgren – and Kilpatrick was harassed all the way back in retreat. The mission was a total failure. What made it even more of a disaster was that when the rebels searched Dahlgren’s body, they supposedly found official orders to destroy Richmond and kill Jefferson Davis and his entire cabinet. This so outraged the Confederates, that Abraham Lincoln would approve the killing of their president, that some came to believe that a southern plot to assassinate Lincoln had its origins that day as a result of the failed Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid.

The portrait of Ulric Dahlgren is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. News clippings are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Veterans’ File Card is from the Pennsylvania Archives.

;

;

Comments