School Book Maps of the War in the East

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 16, 2012

A study of the Civil War has always been an integral part of U.S. history courses offered in schools and colleges. Maps of the physical area of conflict are usually included to supplement the text and to give some idea of as to the extent of the conflict – including the battles and skirmishes in the northern state of Pennsylvania. Four history textbooks covering a period of time of over 100 years were examined to determine how Pennsylvanians were included in the study of the Civil War – and how maps were used to show the residents of the Lykens Valley area that they lived in a geographic area that was under direct attack by the Confederacy. The first two books, also the earliest, were actually used in the Gratz schools and copies are in the collection of the Gratz Historical Society.

For each of the maps an analysis will be done to determine if Harrisburg was shown on the war map and if the strategic importance of Harrisburg and the area around it could be determined from the map, and how the text itself portrays Harrisburg’s strategic importance.

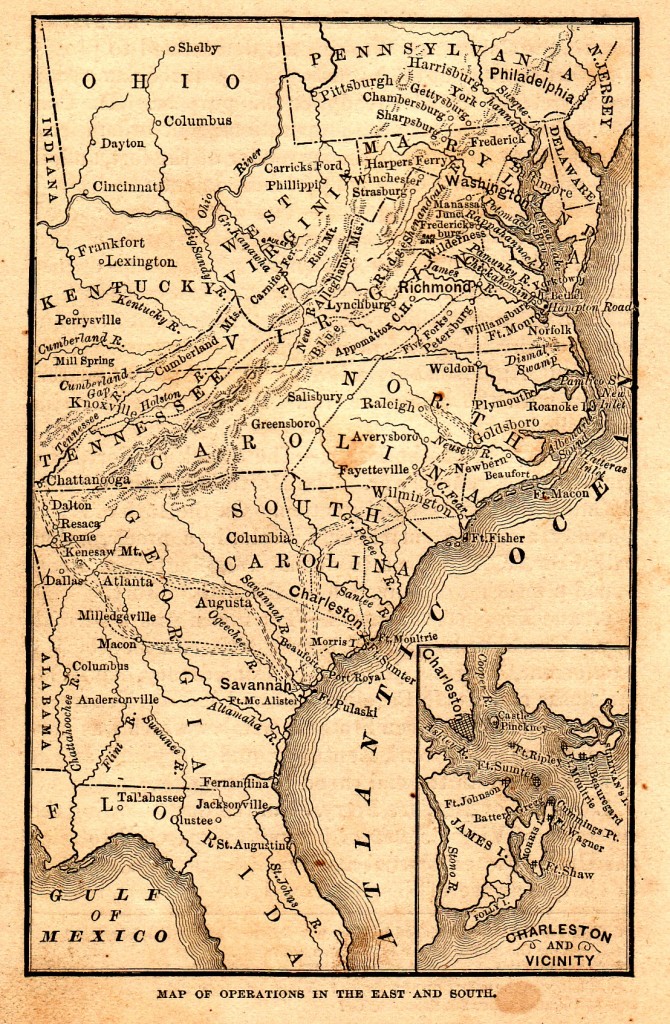

The first map is from a textbook published in 1878, A Smaller History of the United States from the Discovery of America to the Year 1872, by David B. Scott. This book was in use in the Gratz public schools in the period after the Civil War and undoubtedly was read by the children and grandchildren of many of the veterans who served in the war. The title of the map is “Map of Operations in the East and South.” The size of the map is approximately 3.25″ x 5.25″ (click on any map to enlarge it).

The main feature of this map is that it shows the broad area in which the conflict took place. Note that almost the entire states of Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey are shown and in Pennsylvania, the cities of Harrisburg, Philadelphia, York, Gettysburg, Chambersburg, and Pittsburgh are named. The Susquehanna River and its strategic location flowing into the Cheseapeake Bay is shown. From this map, it is easy to show how “father” or “grandfather” who fought in the war, was defending the “homeland” of the Lykens Valley.

The text (Sections 63 & 64) notes the following:

63. Second Invasion of the North – Lee, then, for the second time, invaded the North. Rushing rapidly down the Shenandoah Valley, he entered Pennsylvania and created great alarm. The Union army, re-enforced, and now commanded by General Meade, followed, and took a strong position on the hills near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Here Meade was attacked by Lee, July 1.

64. Gettysburg and the Results – The battle lasted three days, to the close of July 3. Lee was everywhere repulsed, and on the 4th he recrossed the Potomac, and fell back to the south bank of the Rapidan. The Union army followed to the north bank of the same river, but there was no further fighting between them during 1863.

The children of Gratz (and others who used this early text) also had the advantage of living personages who could relate stories of valor and courage in the defense of Pennsylvania.

——————————

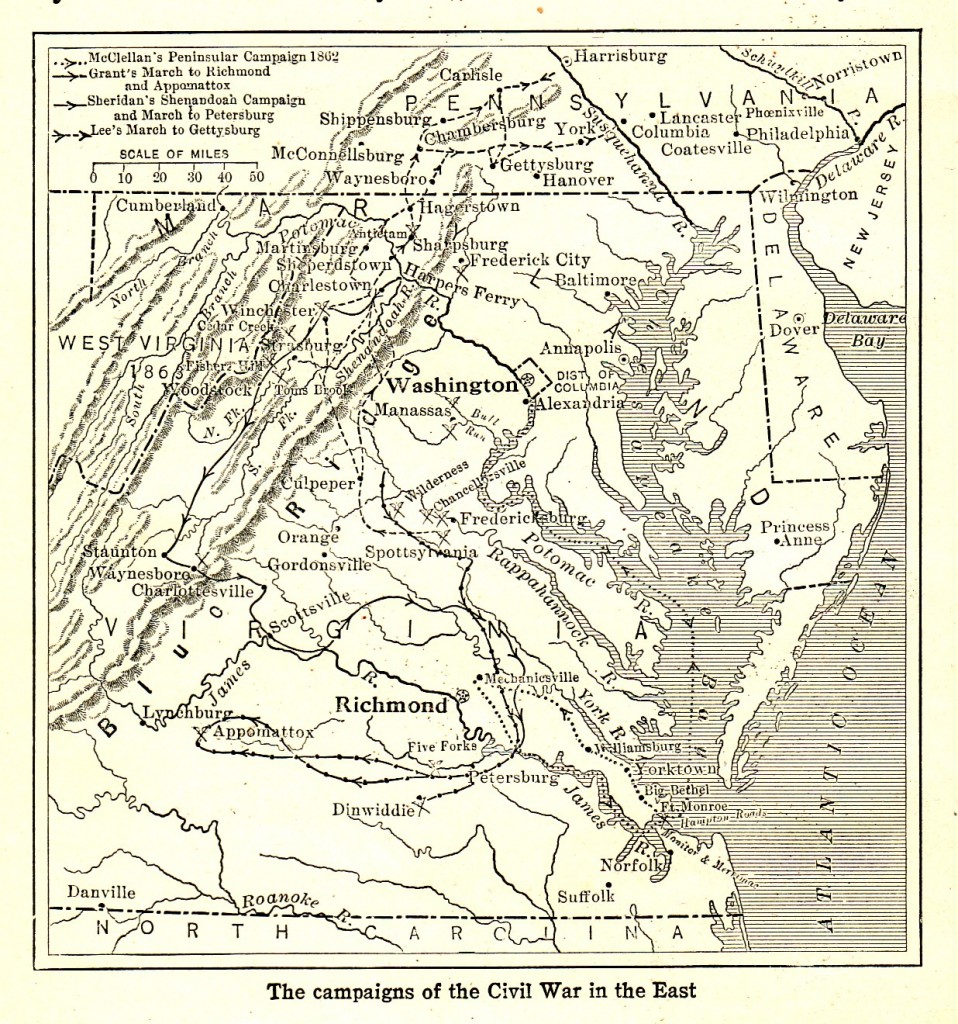

The second map is also from a textbook used in the Gratz schools. Published in 1918, the School History of the United States was written by historian Albert Bushnell Hart. The map entitled, “The Campaigns of the Civil War in the East,” was about 3.75″ x 4″ and in addition to cutting off just below the border of Virginia, the map also cut the state of Pennsylvania in half – and although Harrisburg just made it on the edge of the map, the school children of the Lykens Valley area had to locate Gratz above the map and not on it. The map does indicate many Pennsylvania towns and cities and clearly shows the Susquehanna River (although only from Harrisburg south) and its flow into the Chesapeake Bay.

The text briefly told the tale of the Battle of Gettysburg:

In the East, after defeating the army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville, Lee made what proved to be the last attempt to penetrate the North by a southern army. York and other towns in Pennsylvania were captured by the Confederates, and Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York were alarmed. General George E. Meade was put at the head of the Union army and threw it across the path of Lee at Gettysburg. On the third day of terrible fighting, Lee made his last effort by ordering Pickett’s division of 15,000 men to charge on the Union lines (July 3). The gallant effort failed: a few Confederates reached “the high tide of the Confederacy” on the ridge south of the town, but the attack was hurled back. The next day, the Confederates retreated, and from that time to the end of the war Lee’s army was on the defensive.

Not as many veterans were alive in 1918 and later. Their stories were not as easy to find by the generation of school children who more closely related to the Great World War than its distant “cousin” from the 1860s.

——————————

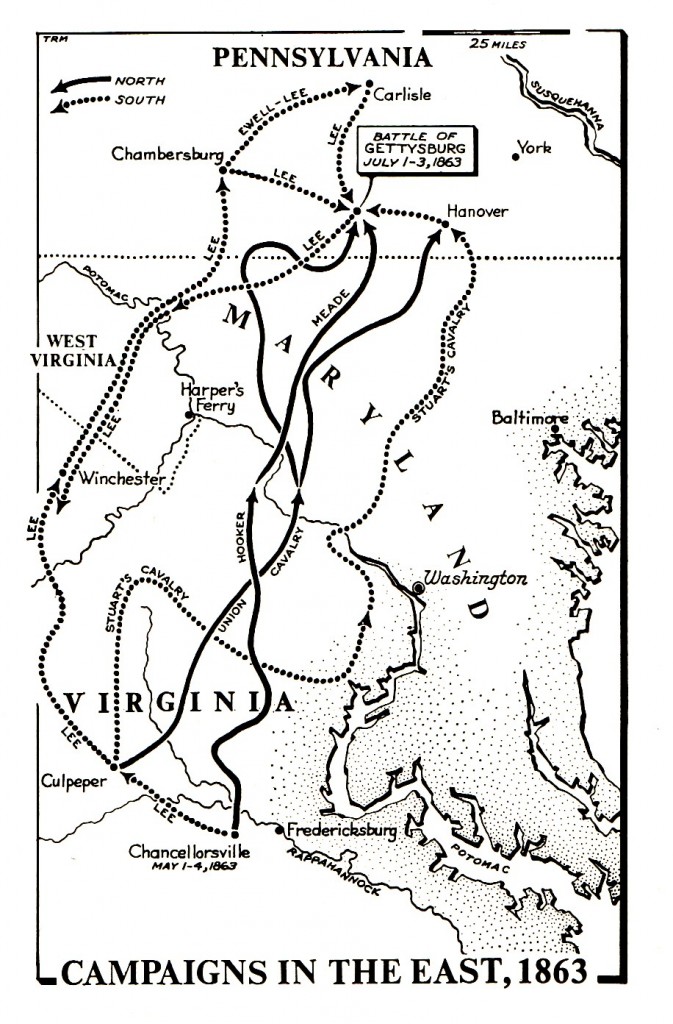

The next map is entitled “Campaigns in the East” and is from a college textbook published in 1962, The United States of America: A History, Volume I, by Dexter Perkins and Glyndon G. VanDeusen. It is approximately 2.75″ x 4″. Unfortunately, Harrisburg is not even on the map (as if there was no strategic value in its location) – and even worse, the Susquehanna River appears to begin south or near the location of Harrisburg instead of well north of Harrisburg where its origin is actually located.

The text states:

…On June 28, George Gordon Meade became commander of the army — just in time, for Lee had pushed 80,00 men up the Shenandoah Valley and into southern Pennsylvania on his last and greatest invasion of the North.

Lee took Chambersburg, Carlisle, and York, in Pennsylvania, and menaced Baltimore and Washington. When Meade moved westward, north of the Potomac, threatening to cut the Confederate line of communication, Lee concentrated his army at Gettysburg. The two armies met there July 1-3, 1863, in the biggest and bloodiest battle ever fought in the United States….

——————————

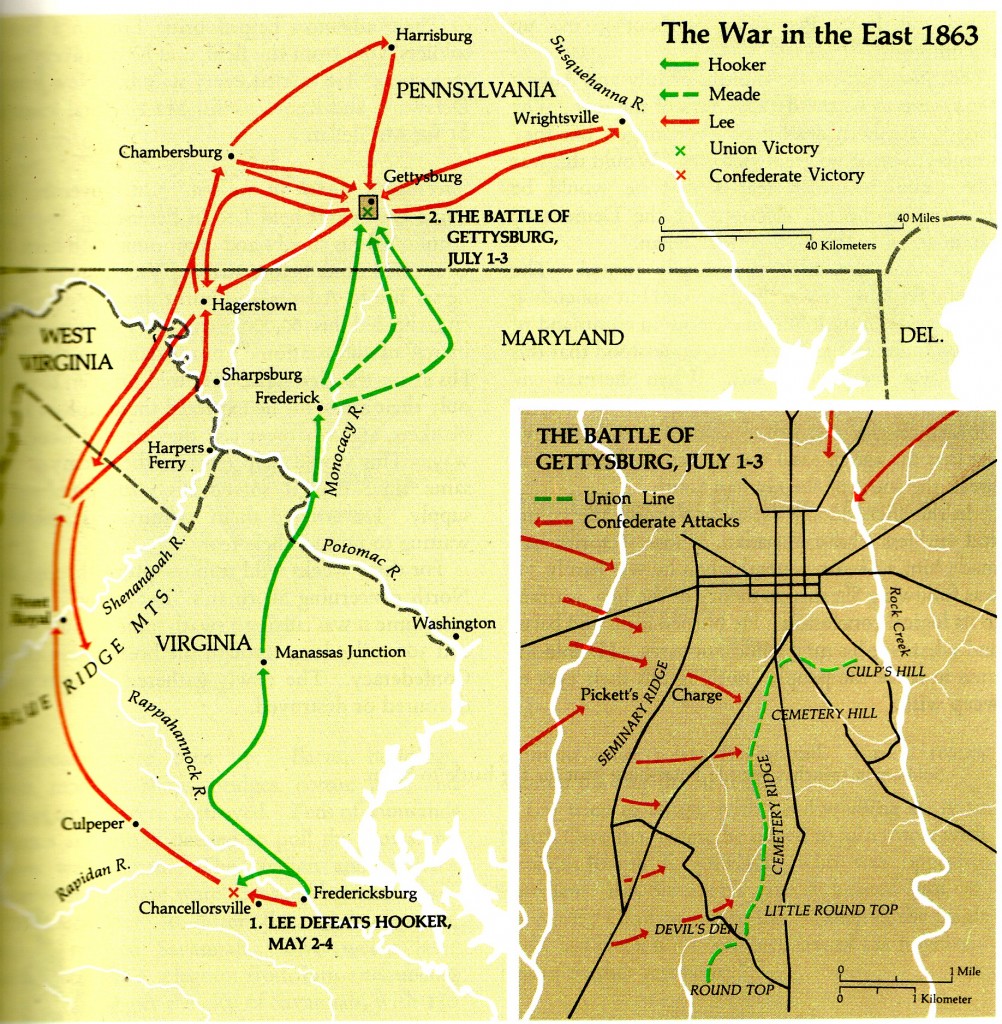

The last map is from a popular high school textbook published in the 1980s and co-authored by historian Daniel J. Boorstin (who also served as the 20th Librarian of Congress). It was entitled A History of the United States. The map of reference for the “War in the East 1863″ was in color and was about 6.25″ x 6.25” with a special inset for the Battle of Gettysburg.

One thing readily apparent from the map is that Harrisburg is on the wrong side of the Susquehanna River, although Harrisburg is noted as well as Lee’s movements in and around Harrisburg. Students from the Lykens Valley area would have trouble finding the approximate location of Gratz and Millersburg because of the misplacement of Harrisburg. And, by only showing the narrow confines of the 1863 movements of Lee into Pennsylvania, the greater strategy of the Confederacy is left in question by only reading the map. The text does help clarify some of the objectives of the campaign.

President Davis and General Lee now decided to invade the North. They still hoped that a decisive victory might demoralize the war party in the north, lead to the election peace Democrats in the fall elections, and bring foreign recognition of the Confederacy.

The Battle of Gettysburg. With this large purpose in mind, Lee crossed the Potomac on June 11, 1863, leading an army of 70,000 men…. Units of the two armies stumbled into each other at the sleepy town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Both armies then hastened to the spot. Here 165,000 men were to fight the greatest single battle ever to take place in the Western Hemisphere….

—————————–

A few final thoughts. The first two maps clearly show the mountainous terrain, while the most recent ones do not. None of the maps show the railroads, which were a major reason in the development of the strategies of the war. None of the maps show the territory that was under the military control of each side.

Other maps will be presented at a later date.

This is the 73rd post in an ongoing series on the Battle of Gettysburg.

;

;

Comments