Halifax Bank Robbery – Abraham Fortenbaugh

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on November 7, 2011

The Halifax Bank, the first bank in the Borough of Halifax, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, was organized in 1871 and was located on Market Street. By October 1900, the Halifax Bank bank closed and was re-established as the Halifax National Bank. Within a year, a robbery attempt was made at the bank which resulted in the death of its cashier, Charles W. Ryan. The robbers were captured, a speedy trial was held, and less than a year later they were hanged in Harrisburg – at a public hanging in which more than 1000 persons came to witness.

The story of the bank robbery has been approached from many perspectives and today, there is an exhibit at the Halifax Area Historical Society at the old Methodist church, 3rd and Market Streets, which displays original documents from the trial and photographs of the execution. The visitor to the Society is first greeted upon entry into the Methodist church with a large safe from the old Halifax National Bank of 1900 – and the parking lot behind the old church near where one of the robbers was captured, is now owned by the bank, which has re-located to the northeast corner of 3rd and Market Streets. The old bank building, farther down the street, is now a private residence. In the year 2000, the Halifax National Bank produced a commemorative booklet on its “100th Year” and again detailed the story of the robbery as one of the defining incidents in its history. Over the years, the Halifax bank robbery of 1901 has become the focus of several programs of the Halifax Area Historical Society and has been variously described in periodical articles. When the robbery and shooting occurred, it made headlines in newspapers throughout the country. Likewise, the trial and execution of the robber-murderers was also eagerly awaited news. Reporters descended on Harrisburg trying to get every possible detail of how the accused were responding and how remorseful they were for their deeds. The execution was described down to the last detail including how long it took before the doctors could make the death pronouncement. In one of their final statements, the convicted killers of Charles W. Ryan attributed their bad ways to too much reading of trashy western novels of the Jesse James ilk.

One of the aspects of this story that has not been thoroughly examined is the history of the banking system in the United States and how the Civil War fit into that history. Today, the Federal Reserve System is our “National Bank” and issues national currency. But in the days prior to the Civil War, there was no national currency. Paper money was issued based on reserves of gold or silver held by the government, but for the most part, transactions were done in specie, or actual gold or silver, usually represented by coin. The Civil War created huge expenditures for the Union and in order to finance the effort, about $150 million in “greenbacks” were issued. According to one source:

The bills were backed only by the national government’s promise to redeem them and their value was dependent on public confidence in the government as well as the ability of the government to give out specie in exchange for the bills in the future. Many thought this promise backing the bills was about as good as the green ink printed on one side, hence the name “greenbacks.”

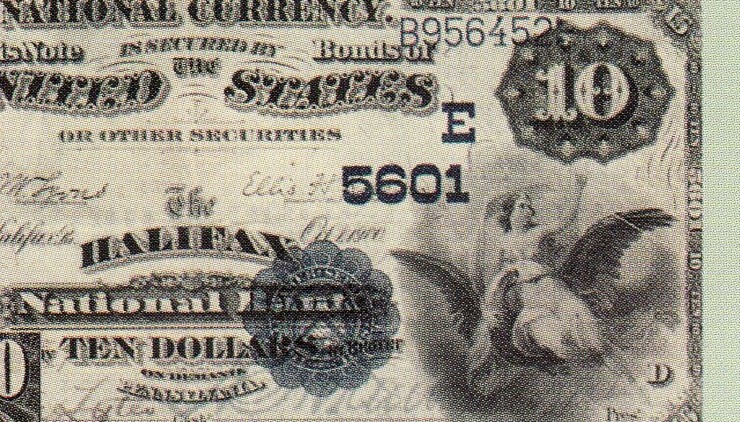

The original banking act, known as the National Currency Act of 1863, attempted to create a single national currency by allowing chartered banks to issue bank notes that were backed by the government. The notes were printed by the government and issued to the banks only to the extent of the capital that the bank directors had deposited in the national treasury. State chartered banks could still exist, but any currently they issued became taxed at a level where it was not economically prudent to issue currency – thus driving the state currency out of circulation. The National Currency Act of 1864 was passed to establish federally issued bank charters and this took banking out of the hands of state governments. These two currency acts were a direct result of the Civil War and the huge expenditures encountered by the Union – and they represent in the economic realm, a major shift between the role and power of the states and the role and power of the central government.

Under the new rules, it took a large amount of capital to establish a national bank. States could still charter banks, but the capital required to do so was much less – and they could not issue currency. Because of the low amount of capital required to charter a state bank, the number of state banks grew significantly in the period prior to 1913. The dual banking system (national banks that could issue currency and state banks that could not) was an unusual arrangement that fueled the growth of the United States during the Gilded Age, industrial revolution, and great period of immigration between 1890 and 1910. But the arrangement also caused a great deal of concern in presidential election campaigns and there were a number of financial “panics” that occurred during this period.

The Halifax National Bank, according to its “100th Year” booklet, was captitalized at $25,000 which involved 250 shares that were sold at $100 apiece. The original shareholders included three men who will be discussed in this post and the two days following. First, Abraham Fortenbaugh, owner of 10 shares, was elected as a director and was the first president of the bank. The cashier of the new bank was Charles W. Ryan who also owned ten shares. The assistant cashier was Isaac Lyter, owner of five shares. All three men were present in the bank on 14 March 1901 when two other men, Weston Keiper and Henry Rowe entered the bank with the intention of robbing it. The first three posts will look at each of the men in relation to their genealogies and Civil War connections. The final post will examine the lives of the two robber-murderers and one of their accomplices.

Abraham Fortenbaugh was born in Newberry, York County, 5 August 1838, a son of Samuel B. Fortenbaugh, a butcher, and Mary Eve [Miller] Fortenbaugh. In 1860, he was working as clerk while still living with his parents. Three brothers had died young: Samuel Fortenbaugh, at age 7 in 1851; a second Samuel Fortenbaugh, at about age 2 in 1853; and Robert Fortenbaugh, at about age 2 in 1856. Likewise, two sisters had also died: Mary Anna Fortenbaugh, the first-born of the family, who survived less than a year before Abraham was born; and Annie Fortenbaugh, who was born just after Abraham, and likewise died young. Only one sibling had survived at wartime, Mary Ellen Fortenbaugh, who like her brother Abraham lived to old age.

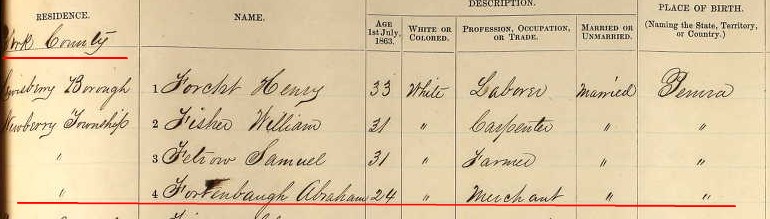

For whatever reason, the young Abraham chose not to enlist in the war. On the 30 January 1862, Abraham married Mary Elizabeth Byrode, and they commenced having children while living in Newberry. Their first child Seward Byrode Fortenbaugh was born 10 February 1863, just a few months before York County began to be overrun with Lee’s invading army. No personal reminiscences have been located on how the young couple fared during the Gettysburg campaign. When the national draft registration took place in July 1863, Abraham Fortenbaugh did his duty and registered – as a 24-year old merchant living in Newberry Township who was married and who was born in Pennsylvania. He was never called to duty.

A second child was born 26 November 1864, Mary Ellen Fortenbaugh, and family records indicate the birth took place in Halifax, Dauphin County, so by this time the family probably had re-located from York County, perhaps as refugees. In a short time after the birth of Mary Ellen, on 17 February 1865, Seward died. Family records record the death in Halifax. In years to follow, two other children were born to the couple: Katherine Elizabeth Fortenbaugh, born in 1867, and Samuel Byrode Fortenbaugh born in 1869. More will be said on the last two children in an epilogue to this series of posts.

Just after the war ended, in May 1866, Abraham Fortenbaugh‘s father Samuel B. Fortenbaugh died. Family records do not indicate whether he died in York County or whether he had re-located elsewhere. His place of burial has not yet been found. Abraham’s mother, Mary Eve [Miller] Fortenbaugh, supposedly lived to 1881, but her place of death and grave have not yet been located either.

Census records for the Fortenbaugh family have not yet been found for 1870 or 1880, and the 1890 census was lost. There are two records for Abraham from 1900 – the census and a passport application. The Census of 1900 shows Abraham Fortenbaugh living in Halifax and working as a merchant. The passport application confirms other information about him, including information about his wife, Mary Elizabeth. In 1907, Abraham Fortenbaugh and his son Samuel Fortenbaugh are found on ship list returning from Havana, Cuba. In the 1910 Census, Abraham has relocated to Harrisburg, where his occupation is given as banker. In 1920, still in Harrisburg, he is listed as a bank director. In 1927, Abraham Fortenbaugh died at the age of 88 in Harrisburg.

More information is sought on Abraham Fortenbaugh and his family, especially the reasons he re-located to Halifax and whether there was a relationship to the Civil War. There are also the “missing years” between the 1870s and 1900 where he has not yet been located in the records. Anyone with information to contribute is urged to do so!

Tomorrow, the story of Isaac Lyter, the teller and assistant cashier was present at the Halifax National Bank the day of the robbery and who helped to subdue the robbers.

The picture of the Halifax National Bank and the picture of the national currency issued by the bank are from the 100th anniversary booklet produced by the bank in 1900. The portrait of Abraham Fortenbaugh is from a Dauphin County history. The 1863 draft registration form is from Ancestry.com. Some of the information on national banks was taken from Wikipedia. The Halifax Area Historical Society has headquarters at the old Methodist church at 3rd & Market Streets, in Halifax (Halifax Area Historical Society, P.O. Box 72, Halifax, PA 17032). Hours are by appointment.

;

;

Enjoyed reading Fortenbaugh. Look forward to tomorrow’s Lyter info.

VOTE tomorrow!