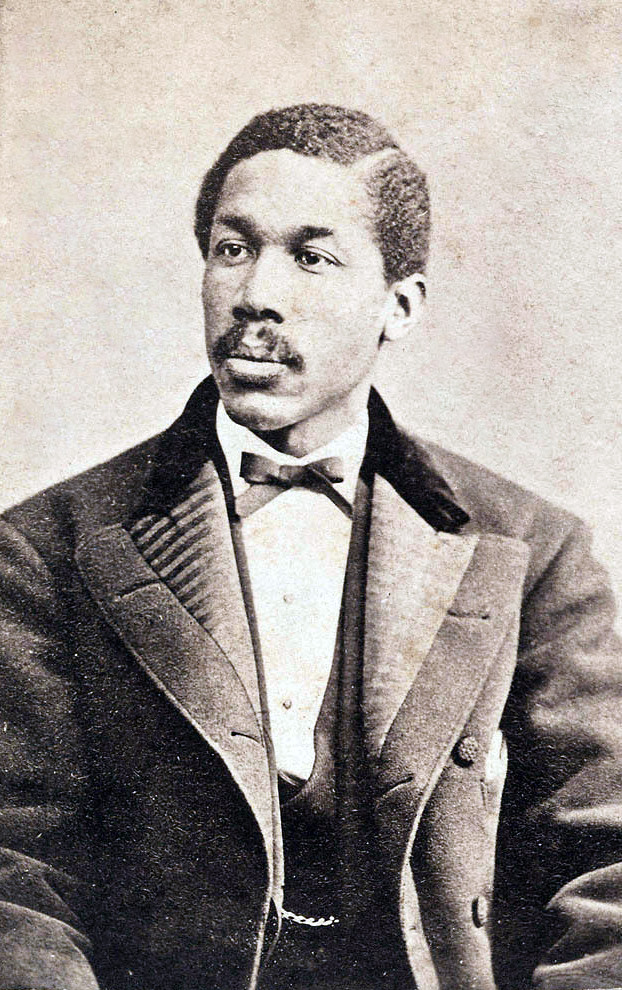

Octavius V. Catto

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on July 6, 2011

The story of Octavius Valentine Catto (1839-1871) gives researchers an interesting opportunity to connect the events of his life with major events in Pennsylvania – and in particular with members of the Gratz family in Philadelphia and events that were happening in Gratz Borough, Dauphin County. Octavius Catto was the son of a former slave from South Carolina, William Catto, who, after being ordained as a Presbyterian minister, took the family north, first to Balitimore and then to Philadelphia. The bustling activity of both Baltimore and Philadelphia made a strong impression on the young Octavius. In Baltimore, the recently completed rail line of the Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad gave promise of easy travel and the flow of commerce into the interior of Pennsylvania, and with the announced plans to extend the line north to Sunbury, the Lykens Valley area would be connected to the port city of Baltimore and points south. Philadelphia had its own attraction, being the fourth largest city in the world with more than a half million people. Just as Octavius Catto arrived in Philadelphia, a consolidation was about to take place which would make the county and city one and the same – with old towns like Kensington, Moyamensing, and Northern Liberties becoming one with the city. African Americans accounted for only about 4% of the total population in a city that had more than two-thirds native born population (New York was about 52% native born in comparison). Descendants of German and Irish made up the largest group of ethnics, accounting for about 25% of the population.

The young Octavius soon learned about the segregated facilities in Philadelphia. He attended the Lombard Grammar School and later was a student at the Society of Friends Institute for Colored Youth (ICY). He did have a brief experience at the all-white Allentown Academy in New Jersey. The curriculum at these schools included Latin, Greek, and higher level mathematics. When Catto graduated in 1858 from ICY, he was congratulated for his exemplary achievements and then did post-graduate work for a time in Washington, D.C. In 1859 he returned to Philadelphia, this time as a teacher at ICY. During the Civil War years, he was a teacher at ICY and often spoke out about the insensitivity of white teachers to African American youth and their needs. On the Civil War, he believed that the government had to “evolve” in order to change and that change must be for the benefit of America’s welfare. Any positive change would therefore benefit all Americans, not just one class or ethnic group.

In 1863, when the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania was imminent, Catto attempted to sign up African Americans to fight for Union and emancipation. The company of volunteers he raised was refused by the staff of Major General Darius N. Couch because Couch believed they were not authorized to fight. The men were sent home to Philadelphia. Eventually, after the United States Colored Troops were established, Catto, along with Frederick Douglass and other abolitionist leaders, were able to recruit eleven regiments. Catto received a commission as a Major, but he was not involved in any fighting.

In a speech given at the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on 21 April 1865, Catto presented the regimental flag to the commander of the 24th United States Colored Troops.

The speaker then paid a tribute to the two hundred thousand blacks, who, in spite of obloquy and the old bane of prejudice, have been nobly fighting our battles, trusting to a redeemed country for the full recognition of their manhood in the future. He thought that in the plan of reconstruction, the votes of the blacks could not be lightly dispensed with. They were the only unqualified friends of the Union in the South. In the impressive language written on this flag, “Let Soldiers in War be Citizens in Peace,” the Banks policy may plant the seed of another revolution. Our statesmen will have to take care lest they prove neither so good nor wise under the seductions of mild-eyed peace, as heretofore, amidst the tumults of grim-visaged war. Merit should also be recognised in the black soldier, and the way opened to his promotion. De Tocqueville prophesied that if ever America underwent Revolution, it would be brought about by the presence of the black race, and that it would result from the inequality of their condition. This has been verified. But there is another side to the picture; and while he thought it his duty to keep these things before the public, there are motives of interest founded on our faith in the nation’s honor, to act in this strife. Freedom has rapidly advanced since the firing on Sumter; and since the Genius of Liberty has directed the war, we have gone from victory to victory. Soldiers! Accept this flag on behalf of the citizens of Philadelphia. I know too well the mettle of your pasture, that you will not dishonor it. Keep before your eyes the noble deeds of your fellows at Port Hudson, Fort Wagner, and on other historic fields. Desert them not. Accept, Colonel, this flag on behalf of the regiment, and may God bless you and them. (Christian Recorder, April 22, 1865)

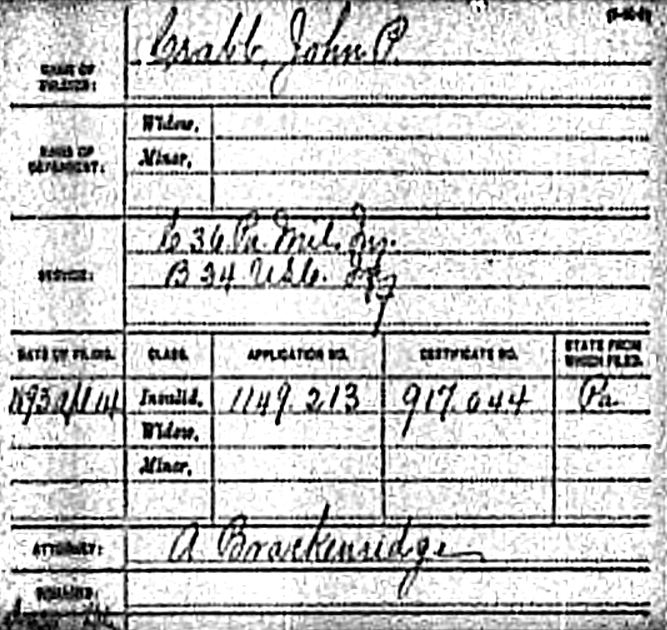

Not known to Catto at the time, a member of the 24th United States Colored Troops, Corp. John Peter Crabb (1843-1901), a blacksmith from Gratz, Pennsylvania, was in the audience. Corp. Crabb served 26 January to 1 October 1865 in the 24th United States Colored Troops. John Peter Crabb had achieved what Octavius Catto had not been able to do in 1863. He served in the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry, Company C, during the emergency of 1863. It is not known how many African Americans served in integrated units prior to the establishment of the United States Colored Troops, but perhaps Crabb’s service had something to do with the rural society in the Lykens Valley area where the Crabb family had established itself – and where the society could not afford to split into ethnic enclaves. All had to work together for protection. When John Peter Crabb applied for a Civil War Pension, he indicated his service in both the 36th Pennsylvania Infantry and the 24th United States Colored Troops as shown on the National Archives Pension Index Card – and he received a pension based on service in both regiments!

An 1865 incident involving Octavius Catto was described in the New York Times. of 18 May 1865. Catto employed civil disobedience tactics in attempting to integrate the trolley system in Philadelphia. The Union League in Philadelphia supported Catto’s attempts at getting a state law passed to prohibit segregation on transit systems. It is not known if segregation was ever an issue on trolleys in the Lykens Valley area, but there were trolleys that ran into the Lykens Valley and connected with the railroad at Lykens. Catto also helped to crusade for the passage of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which was voted upon by Pennsylvania in 1870.

One of the most prominent families in Philadelphia was the family of Rebecca Gratz (1781-1869), who undoubtedly knew of or perhaps met the young Octavius Catto. The Gratz family members were actively involved in many civil causes. It will take more research to determine if there is an actual connection with Catto, but two of Rebecca’s nephews ended up as white captains of United States Colored Troops. Undoubtedly they had men serving under them who Catto had recruited.

The final possible connection with Octavius Catto also involves the Gratz family. In a prior post, it was noted that a “Gratz” played for the Philadelphia Athletics in a baseball game in 1865. Catto was an active cricket player and baseball player in Philadelphia and was a founding member of the Philadelphia Pythian Base Ball Club which was composed of African American players. After the Phythians had an undefeated season in 1867, members of the Philadelphia Athletics supported admitting the team to the Pennsylvania Base Ball Association. When it became clear that their application would not be accepted, the Pythians withdrew. By 1869, the Olympic Base Ball Club accepted a challenge from the Pythians to play a game – which is considered to be the first official match between a white and black baseball team. Since the Athletics supported the application of the Pythians, a conclusion could be drawn that the “Gratz” who played for the Athletics in 1865 knew Octavius Catto. The degree to which any individual gave support to Catto’s cause will have to be left to other researchers, but there does exist the possibility of a strong connection here between Octavius Catto and at least one member of the Gratz family. Baseball proceeded to develop along segregated lines and was not integrated at the major league level until 1947.

Unfortunately, Octavius Catto met his death in 1871 at the intersection of 9th and South Streets in Philadelphia, a victim of racial violence. After working hard to register voters for the Republican Party, which was pro-rights, the ethnic Irish voters who supported the Democratic Philadelphia machine, tried to prevent the African Americans from voting. A clash took place and Catto, who had purchased a gun for his own protection, was killed. The inquest that followed could not determine if Catto had pulled his gun and the result was that, Frank Kelly, who shot Catto, was not convicted. Catto had a military funeral and was buried in Lebanon Cemetery in Passyunk, Philadelphia. His remains were later reinterred at Eden Cemetery, Collingdale, Pennsylvania, where a monument exists to him as “The Forgotten Hero.”

A caricature of Octavius Catto is part of the Road Show of the Pennnslvania Civil War 150.

Reenactor Robert Branch portrays Octavius Catto at the Fourth of July weekend festivities at Franklin Square in Philadelphia, 2 July 2011. Bob is always seeking information on how to better portray this “Forgotten Hero”. He is an avid researcher into the life and times of Octavius Catto.

In March 2011, Philadelphia announced plans to erect a statue in honor of Octavius Catto. Robert Branch is employed by Historic Philadelphia to portray Catto and he moves about the area around Independence Park encountering and educating visitors.

The portrait of Octavius Catto at the head of this post was taken from Wikipedia and is in the public domain. Information for this post was taken from the Wikipedia article on Catto, from the files of the Civil War Research Project, and from an interview with Robert Branch conducted while he was on break during the Fourth of July festivities in Philadelphia, 2 July 2011. The National Archives Pension Index Card for John Peter Crabb is from Ancestry.com. Numerous news articles appear on Robert Branch’s connection with the Philadelphia Civil War Sesquicentennial events and can easily be located through Google by using the search terms “Robert Branch” and “Catto.”

;

;

Comments