Midwives and the Civil War – Specktown’s Becky Rickert

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on March 10, 2011

On the third day of the Battle of Gettsyburg, 3 July 1863, Mary Virginia “Jennie” Wade was killed inside a home by a stray bullet while she was baking bread for hungry Union troops and thus became the only civilian casualty of the battle. Prior to this domestic exercise, she had faithful done her morning devotions and read from the Bible. Her fiancee, John Hastings “Jack” Skelly Jr., a soldier in the Union army (87th Pennsylvania Infantry), had been wounded at the Battle of Winchester and subsequently died days after Jennie died, neither knowing of the misfortune of the other. Jennie’s accidental death made her the “heroine of Gettysburg” and by 1900, the Pennsylvania legislature provided money for a monument in Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg. Why did Jennie stay behind in the town? She was there to give aid to her sister who had given birth days earlier. Jennie was performing a traditional role of women – assisting in the birthing process, which included late pregnancy care of the mother and post-natal care of the child. In effect, she was a “midwife,” although few would have called her that in 1863, and she certainly would not have given her occupation as such.

Much of the story of Jennie Wade became “enhanced” over time, but is what currently being challenged in Civil War historiography is the notion that “separate spheres” existed for men and women and there was no cross-over in gender roles. Jennie became a heroine because she was performing a traditional role of a woman when she was killed. In contrast, the civilian hero of the Battle of Gettysburg, John Burns, was a 70-year-old veteran of the War of 1812 who supposedly took up arms and fought side by side with the Union troops. After the battle, he was hailed as a hero for his efforts which were undoubtedly exaggerated to fit the image of of “manly courage” that was prevalent at the time. Abraham Lincoln even met with Burns when he appeared at Gettysburg in November 1863 to dedicate the cemetery and give his famous address. These two civilian heroes became part of the folklore and legends that emerged in the post-Civil War period. In a previous post, Women and the Civil War on the Northern Homefront, Judith Geisberg‘s book was discussed in relation to both the new roles taken up by women during the war, and specifically, how one woman from the Lykens valley area, took up many of the traditional roles of menfolk during the war. That woman was Elizabeth [Klinger] Schwalm. In her essay “Gender Analysis of Civil Responses to the Battle of Gettysburg,” Christina Ericson, points out that while Jennie was undoubtedly fulfilling the role expected of women and became a heroine because of that, her emergence as the only heroine clouds the true actions of women before, during and after the battle, and the elevation of John Burns as a symbol of a manly response of an elderly citizen does the same for the true actions of the civilian men. Through diaries and other original source material, Ericson documents the assertiveness of the many women who accepted the challenges of the battle and the temporary Confederate occupation of Gettysburg and the empowerment and protectiveness they assumed amidst the trying conditions. Most of the men fled the town and those left behind were too elderly or infirm to take an active role in defense of the women, let alone of the town.

It is not the purpose of this post to discuss the overall role of women in the Civil War on the homefront, but rather to discuss one specific role, that of women in the birthing process, and how that role played out in one small cluster of homes and farms in the Lykens Valley. Along what is now called “Specktown Road” in Lykens Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, is a community that residents called Specktown, although it won’t be found on maps as such. Today, the center of that “town” is approximately at the location of the Lykens Township Veterans Monument which was the subject of a previous post. Among the earliest settlers of Specktown were Martin Rickert (1804-1871) and his wife Elizabeth “Betsy” [Yerges] Rickert (1813-1877).

For a 19th century farmer, having many children was considered a blessing, and boys especially were expected to start working the farm along with their father as soon as they were able. So, Martin and Betsy set out to have a large family. Unfortunately for them, their two sons Samuel Rickert (1850-1858) and Henry Rickert (1835-1837) died young – leaving only seven daughters who survived into adulthood. At the time of the Civil War, five of those daughters had married and several of the husbands were serving in the war. During the war, four of the daughters gave birth to a total of eight children. The special responsibility that Betsy had to her daughters was to make sure that they learned the ways and methods of childbirth and that they assumed the responsibility of assisting each other when needed. The youngest daughter of Martin and Betsy, Hannah Rickert, was born in 1847. Undoubtedly, her oldest sister Elizabeth Rickert, who was about 18 at the time, was present when her mother gave birth for the last time – as was probably also Susannah Rickert who was 14, and Rebecca “Becky” Rickert, who was only 10.

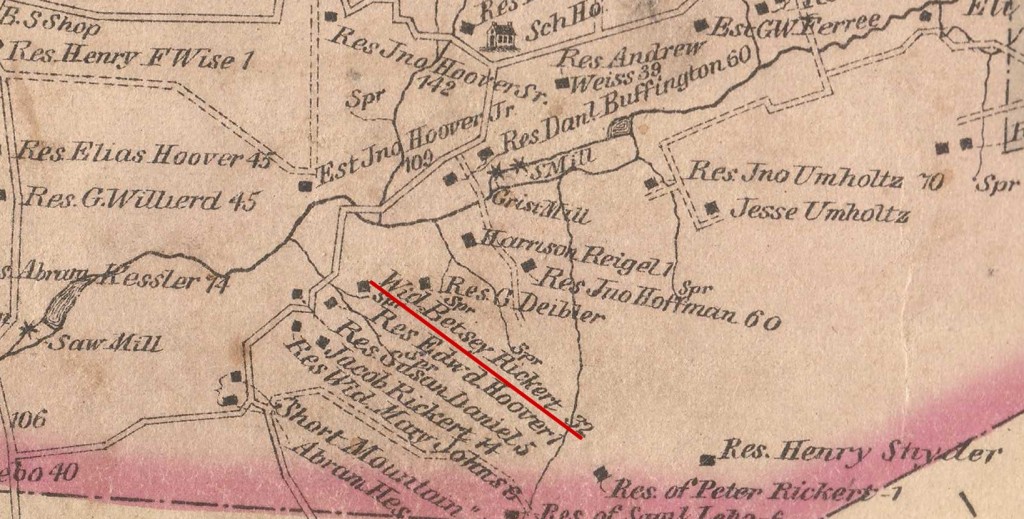

The map above shows the community along Specktown Road in 1876. Underlined in red is the 32 acre farm of the Widow Betsy Rickert. By 1876, her daughters who had married, were settled in the area around her. The home marked “”Res. Widow Mary Johns” (6 acres) – three names below Betsy -is the home that was later purchased by Hannah [Rickert] Riegle after her husband Harrison Riegle died in 1899, and to get perspective on its location, it is currently across New Specktown Road from the Lykens Township Veterans Monument, the subject of a previous post. The road was straightened out in the 1950s to eliminate the sharp curves and replace the old covered bridge over the creek.

Rebecca “Becky” Rickert (1837-1918), as previously mentioned, was probably present at the birth of her youngest sister Hannah and was able to assist in some ways at that birth. During Becky’s early years of life, she suffered from scarlet fever, which left her with some mental incapacity, but not enough that she couldn’t continue to assist in the births of her sister’s children and perform tasks in the home that all women were expected to perform. During the Civil War, she undoubtedly performed the role of midwife or midwife’s assistant at the births of her eight nieces and nephews who were born during the war. When the mother Betsy Rickert died in 1877, Becky moved in with her sister Hannah and assisted Hannah in the births of her later children. She became especially attached to Hannah’s oldest daughter Elizabeth “Lizzie” Riegle (1872-1942) to whom she passed on her skills. It was Lizzie who made midwifery her profession and family oral history confirms that she actually used the title and got paid for her services. As the 19th century closed, Becky was no longer capable of taking charge in childbirth situations nor was she able to do much more than perform simple household task. Friends and family members visited her and brought her picture post cards, which she collected, and conversed with her in “Dutch.” She sat on her rocker, smoked a corn cob pipe, and played with her grand nieces and nephews and other children who came by. Hannah expressed concern that she would die before Becky and that there would be no one to take care of her. But that was not true, for if that had happened, Lizzie surely would have kept her and nursed her in her last days. Becky died about a year before Hannah.

Thus it was that the skills of midwifery were passed down through the generations in Specktown, Lykens Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Betsy Rickert and her daughters, especially Becky Rickert, performed this invaluable service during the Civil War. Lizzie Riegle, who learned the skills from her “Aunt Becky,” made her living by charging families $25 for one months service – two weeks before birth, birth, and two weeks after birth. Although there were country doctors in the late 19th century and early 20th century in the Lykens valley area, and some women chose to rely on their services, the record will show that there was sufficient demand for women who specialized in assisting with childbirth. The only training they had received was as “apprentices” to elder sisters or to their mothers who also performed the same services.

Today, midwifery is a specialty branch of medicine and is available for those who choose to not have a medical doctor assist in the birthing process. According to information found on Wikipedia, use of the term “midwife”, common in ancient times, took a long time to return to common usage and that could explain why the Civil War era women did not use it. In the 18th century and into the 19th century in America, midwifery was associated with witchcraft, particularly because women who practiced it were seen more as “population controllers” because they disseminated birth control information and also performed abortions. This was the era when it was important to have as many children as possible and anyone who tinkered with that idea was seen as devilish or as a witch.

Readers are invited to submit family stories, especially of women who served as midwives during the Civil War period.

Much information for this post was taken from family records. The essay on “Gender Analysis…” by Christina Ericson as cited above is from Making and Remaking Pennsylvania’s Civil War, by William Blair and William Pencak, published in 2001 by Pennsylvania State University. The stories on Jennie Wade and John Burns were taken from Wikipedia articles as well as from the aforementioned essay.

;

;

Great information! Thank you. I’m wondering what a woman who assisted in childbirth was called in the mid-19th century, if not a midwife.