Pvt. Peter W. Miller – Mental Health & the Civil War

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on December 2, 2010

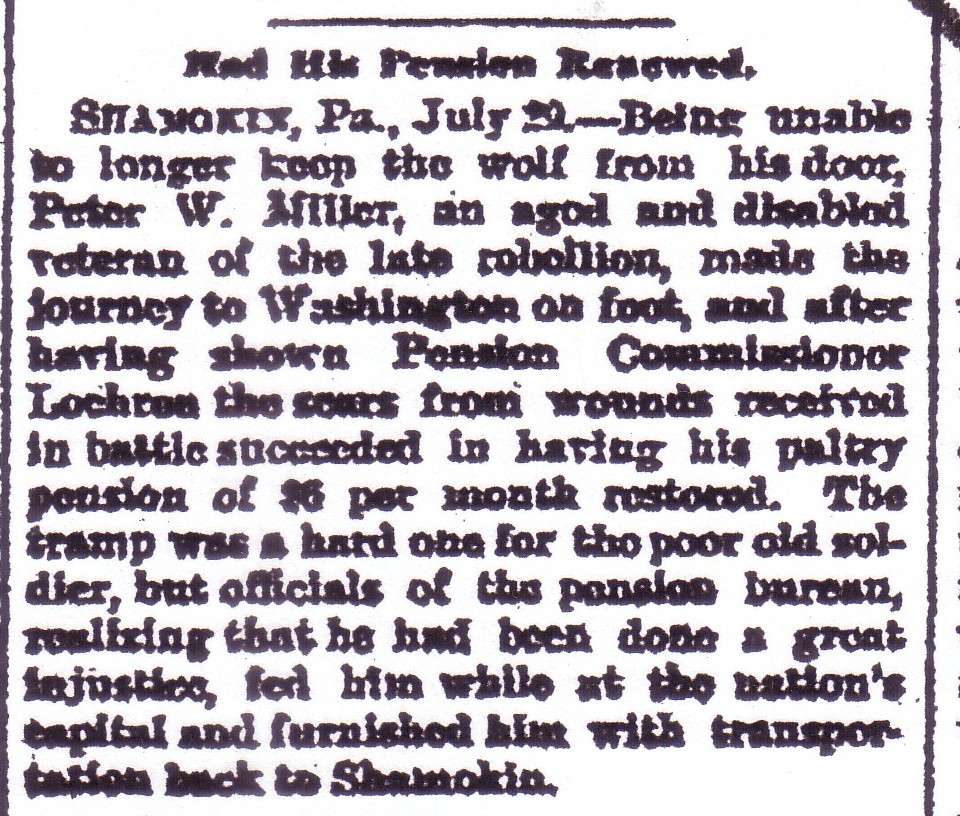

This story appeared in the Tyrone Daily Herald, Tyrone, Pennsylvania, on 29 July 1895:

This story appeared in the Tyrone Daily Herald, Tyrone, Pennsylvania, on 29 July 1895:

Being unable to longer keep the wolf from his door, Peter W. Miller, an aged and disabled veteran of the late rebellion, made the journey to Washington on foot, and after having shown Pension Commissioner Lochran the scars from wounds received in battle succeeded in having his paltry pension of $6 per month restored. The tramp was a hard one for the poor old soldier, but officials of the pension bureau, realizing that he had been done a great injustice, fed him while at the nation’s capital and furnished him with transportation back to Shamokin.

Peter W. Miller was born about 1842 in Schuylkill County (probably Porter Township), Pennsylvania to William Miller, a blacksmith, and his wife Anna Mary [Brown] Miller. By 1860, the household consisted of Peter, a sister Sarah who was 16, and a younger brother Isaac, aged 12. Not much is known of his early family life, except that he probably apprenticed with his father and became a blacksmith on his own before 1865. There are no indications in the records that Peter would be anything but successful in life.

Peter waited until 1865 to volunteer for service in the war, probably because of his age and probably because as a blacksmith, his services were needed at home. Enrollment records indicate he joined and was “mustered in” the same day, 20 January 1865, at Pottsville, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. While the military records indicate he was 19 years old, there is some conflict as to his actual date of birth – probably, it was around 1842. At enrollment, he was found to be of medium build, 5 foot 3 inches in height, brown hair and hazel eyes.

The 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry, to which he was assigned, had already seen a great deal of action – with major fighting at Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and at Petersburg.

On 28 October 1864, the members who had not re-enlisted were mustered out and in November the regiment was ordered to Philadelphia for guard duty during the presidential election. In December, the 93rd Pennsylvania was ordered to Petersburg and there went into winter quarters. Peter, and other reinforcements joined the regiment after the first of the year.

From 27 February through early April 1865, Pvt. Peter Miller was involved in the second engagement at and around Petersburg. Later, the 93rd fought at Sailor’s Creek and then joined Gen. Sherman at Danville, remaining there until ordered back to Richmond. Finally, the regiment returned to Washington, where it was mustered out on 27 June 1865.

While the list of casualties in the 93rd Pennsylvania was not as great as in many other Civil War regiments, Peter surely saw enough death and destruction in the Petersburg engagement to make a lasting impression on him. Thousands were wounded, taken prisoner or killed. The trail of destruction included railroads, bridges and buildings. Factories, mills and warehouses were burned to ashes. Loud explosions and the firing of guns and cannon were constant. Wagons, weapons, horses and personal possessions were abandoned on the battlefield. For a time, the living were preoccupied with the care of the wounded and the removal and the burial of the dead.

It was at this 1865 Battle at Petersburg where Peter was injured. These injuries would plague him the rest of his life.

Peter’s father William recalled that in 1865 when Peter returned home he was sick and complaining of pain in his arms and legs, and it also appeared that “he could not hear as good anymore.” For two years after, he “kept getting poorer all the time” and was “continually using more medicine to keep himself.” His mother Mary, recalled that Peter arrived home in 1865 in “very sick condition… having the diarrhea very bad and also complaining very much of pain in his back and legs…” and “has been complaining since that time to the present [1889].” She often gave him teas to drink to relieve him of pain. “He also don’t hear very good anymore… [and] complains of pain in his ear very often.”

Peter admitted that he was unable to do any work at all for about two years after being discharged from the army.

In Peter’s own words: Loss of hearing was contracted by firing of cannons [on] the second day of April 1865 in the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia. The cause of rheumatism [was] lying on the ground while in the line of duty and was first felt between the 10th and 12th of April 1865.

In 1889, Peter attempted to get his Captain and Orderly Sergeant to verify that his medical problems were related to his service in the war, but they responded that it was too long ago and couldn’t remember anything specific about him as “so much of the kind [was] going on at the time.”

Throughout the entire after-war period of Peter’s life, he sought treatment for his medical problems. Dr. Rose of Tower City administered to Peter’s needs until Dr. Rose died around 1880. From around 1880 through 1885, Peter used patent medicines such as liniments – and the herbal teas from his mother helped him somewhat. When Dr. Rickert came to Tower City around 1885, he began regular visits with him. One of the last surviving written reports on Peter’s medical problems was written by Dr. W. F. Wood on 7 December 1905. Dr. Wood examined Peter at the Veterans Home in Erie, Pennsylvania. At that time, problems in addition to the loss of hearing and rheumatism were noted – including cardiac palpitations and the notation of a scar that resulted from the “bursting of a shell.” This wound and scar had not been noted on any previous report.

Despite the continuing visible effects of his ailments, all of which Peter attributed to his military service, the pension bureau demanded proof. “I refused to go to the hospital,” Peter noted in an early application. It was this refusal, perhaps due to the common Civil War era belief that a hospital was a place to go to die, that resulted in the most problems for Peter. His ailments were not documented at the time and the pension office therefore believed they could not have been war-related.

As each new bill was passed by Congress to increase veteran benefits, Peter sent in his pleas. His walk to Washington occurred in 1895 before he began stints in veteran homes in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Tennessee, and Virginia. In each institution, Peter was required to turn over the full amount of his paltry pension to home officials, the money to be used for his care, leaving nothing for Peter to use to support his family. Also at times, Peter was lodged in the county almshouse.

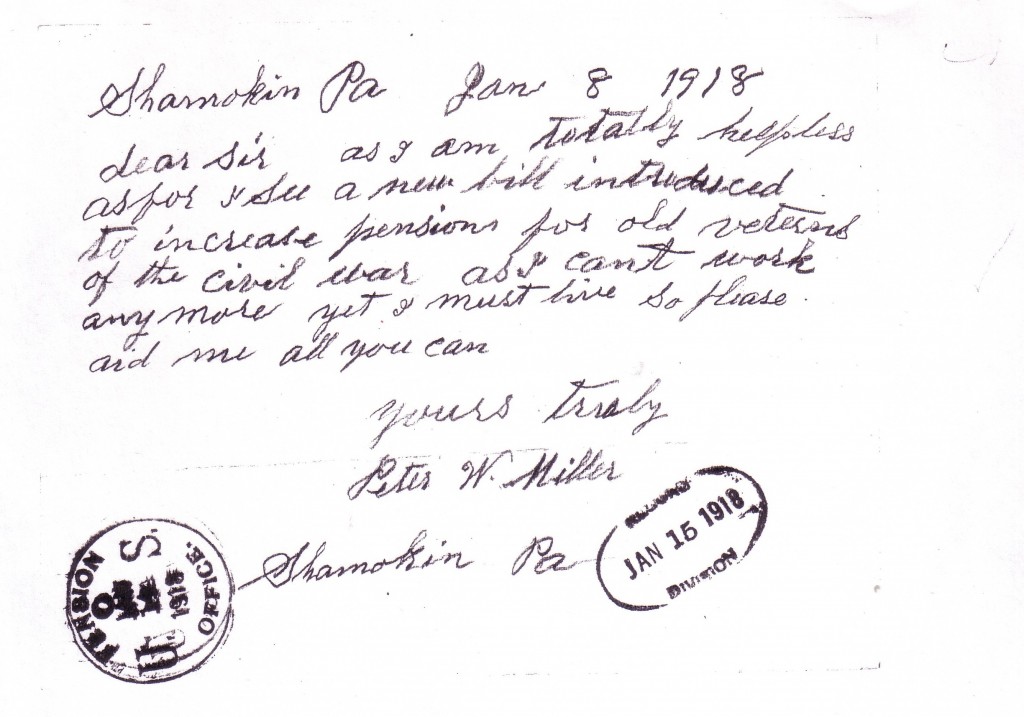

Peter’s final plea for a pension increase occurred in 1918, the year of his death. In his hand, he wrote and signed a letter on 8 January 1918, from Shamokin, Pennsylvania. It was a direct plea – not on any government form, and not with the assistance of any lawyer.

Dear Sir,

As I am totally helpless as for I see a new bill introduced to increase pensions for old veterans of the Civil War as I can’t work any more yet I must live so please aid me all you can,

Yours truly,

Peter W. Miller.

On 28 January 1918, the Pension Commissioner responded that “there was no law by which a greater rate may be allowed for any disability not proved to have incurred in the service and as you have never established a claim based upon disability alleged as if service origin, it is not apparent how this Bureau can afford you further relief at this time.”

Peter’s final indignity occurred when he was admitted to the State Hospital for the Insane at Danville, Pennsylvania, on 16 Mar 1918. Dr. Hugh Meredith, Superintendent of the home, noted that Peter had been admitted from the support of the Overseers of the Poor of Shamokin and Coal Township, Schuylkill County, and that his history noted that he was a heavy drinker.

Peter died on 10 Nov 1918 at the asylum in Danville. The official cause of death was listed as “Organic Disease of the Heart with contributory Senile Dementia.”

About five years after his army discharge, and a few years after Peter was attempting to get back to work, Peter “got drunk” and married his cousin Susanna “Annie” Brown. No children resulted from this marriage, and, as Peter admitted, it was a mistake. So, he filed for divorce, which was granted in Dauphin County Court in 1872.

Six years later, he met and married Sevilla Gilbert of Snyder County, Pennsylvania. Sevilla herself came from a background of difficulties. Her mother had married several different men and after having children with each, broke up the families. Sevilla was raised by her grandparents. She also had a three-year old son who was fathered by a saw mill worker named Linn Yeager who Sevilla claimed got her “into trouble” when she was eighteen. No marriage took place and Yeager disappeared from the scene leaving Sevilla and her son Charles without support. No doubt, Sevilla throught, the marriage to Peter Miller would give her and her son Charles Yeager a respectable home. Peter took in the step-son and helped raise him. In the ensuing years seven children were born to Peter and Sevilla, with one dying in infancy.

At the time of the marriage, Peter had moved to Snyder County and began working in a blacksmith shop there. On the surface, things seemed to be going well. As the years went on and the children grew, Peter’s symptoms became worse. He took to drinking and disappearing for periods of time. Then he stopped working. He went begging from house to house, angering the neighbors. At some point the family moved to Rush Township in Dauphin County and then later to Coal Township and Shamokin in Northumberland County. Sevilla indicated that he was a “bum” and when he was home he was “lying around” and complaining. On one occasion Sevilla had him arrested for beating two of their sons. On other occasions he was arrested for being a nuisance and for being drunk.

Around 1902, Sevilla and Peter agreed to a separation, although on occasion, Peter returned home for a meal and a place to stay. Throughout this period, Sevilla had no idea where he was living or how he was supporting himself beyond the pension he was getting. She knew from experience that he most likely was binge drinking when his monthly pension check arrived. Only the step-son Charles kept in contact with him.

When Sevilla tried to appeal to get half of Peter’s pension, her daughter Maggie tore up the papers, leaving Sevilla at the mercy of her daughters who provided some support for her such as rent payment or taking her in their own homes for periods of time. But the children had families of their own and couldn’t support Sevilla fully, so while she could, she worked as a washer woman and as a nurse, did gardening and other odd jobs that women were permitted to do, and tried to support herself the best she could. At no time did she apply for a divorce. Peter also did not apply for a divorce. And, both Peter and Sevilla, for whatever reason, never “took up” with another. Although they were separated, the legal bond of their marriage remained in effect throughout their lives.

After Peter died, much of the family grief was spilled out at the depositions that were required so that Sevilla could get a widow’s pension. She had to prove she was never married to Linn Yeager. She had to prove she had never received a divorce from Peter. The children had to describe their relationship with their father in detail – including describing his behavior and referring to him as a “drunk” and as a “bum.” This was not pleasant for a family that already had suffered through years of Peter’s medical and mental difficulties.

In retrospect, this was an era when mental disorders such as post-traumatic-stress-disorder and depression were unknown to medicine. While Peter received treatment for the physical problems that he associated with his service in the war, his mental health was left untreated. The family had no recourse but to tolerate what was happening – or throw him out. So that’s what happened. He was thrown out.

The traumatic effects of even a short-time military service were evident in Peter’s physical symptoms and in his behavior – but there was no one around who could diagnose that – or provide treatment. The medical system crudely handled the physical issues. The pension plan provided meager compensation, mainly because of the soldier’s age – unless the injury could be directly attributed to the military service, which the pension bureau claimed wasn’t. The veteran homes provided a bed, meals, and some medical care – at the expense of surrendering the meager pension check. There was no counseling available for the veteran or his family – no treatment of the mental health issues that dominated the post-war experiences of this family.

Sadly, the case of Pvt. Peter W. Miller, who served five months in the Civil War, who received an honorable discharge from the 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry, is not unique. To a greater or lesser degree this type of story was repeated too many times. Sevilla died in 1925 at the age of 69, a widow for about seven years, partially supported by the small pension she finally received as a result of Peter’s old age, and not as any result of his injuries from the war. Peter died in 1918 in Danville and is buried in Shamokin Cemetery, Shamokin, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

Note: Many thanks to a direct descendant of Peter W. Miller and Sevilla [Snyder] Miller for providing documents for this story, including extensive information from the Pension Files from the National Archives and the news clipping from the Tyrone Daily Herald. By itself, the story of the “one-man-march on Washington” by Pvt. Peter W Miller is amusing, but in the context of the realities surrounding it, it takes on a different meaning.

;

;

I am so grateful for your blog article.Thanks Again. Really Great.