Corp. John C. Gratz – 96th Pennsylvania Infantry

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on December 16, 2010

(Part 3 of 4). The 96th Pennsylvania Infantry was organized at Pottsville, Schuylkill Co., Pennsylvania. It was mustered into service between the 23 and 30 September 1861 for a three year term. This post focuses on the service of John C. Gratz in that regiment, and of his friend Henry Keiser who served with him.

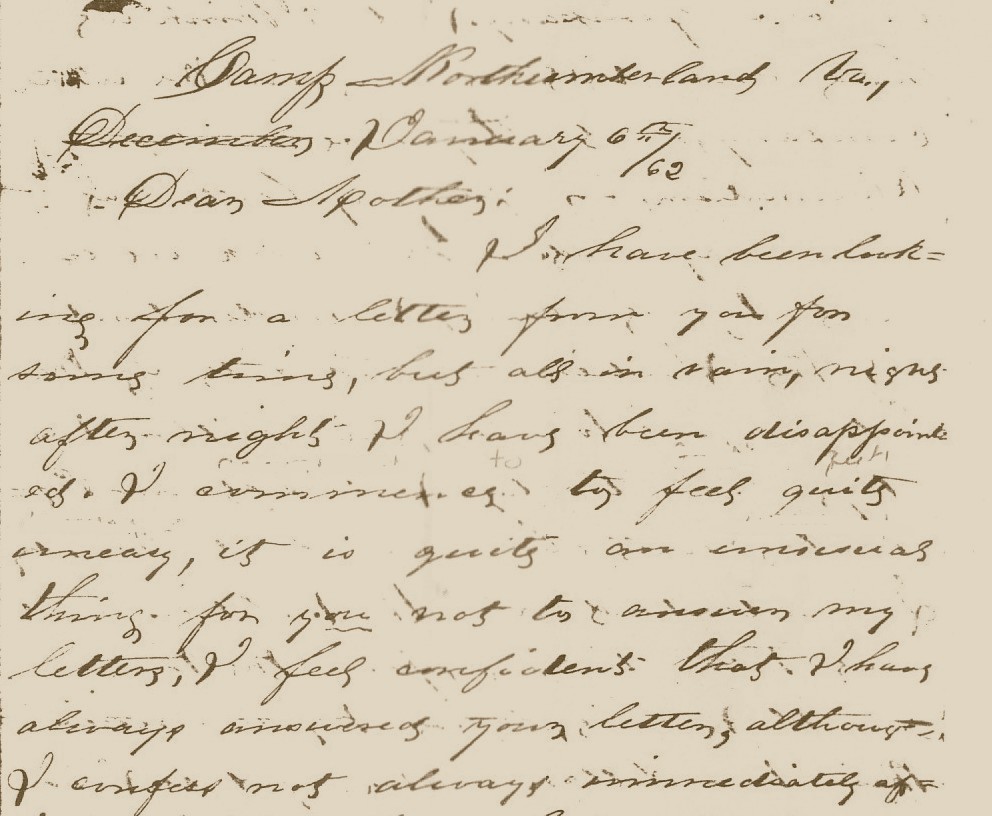

For the story of the early days of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry, we can consult three sources available at the Gratz Historical Society. The first source, is The Diary of Henry Keiser, previously mentioned. Henry Keiser began keeping his diary on Monday 23 September 1861, the date on which the “boys from Lykens… enlisted.” The second source is a 6 January 1862 letter written by John Gratz to his mother about 20 days before he died. The third source is the official history of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry.

As previously mentioned, both Henry Keiser and John C. Gratz had served in the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry and were mustered out on 31 July 1861 at Harrisburg. Nothing specific is known about either during the summer of 1861. We can speculate that because they were denied the fight that they were seeking due to the cautiousness of Gen. Robert Patterson, that they desired to join another Pennsylvania regiment and get involved in the war. By September 1861, it was becoming more obvious that there would be no quick victory for the Union and that many more men would needed to put down the rebellion.

On 23 September 1861, both men. John C. Gratz and Henry Keiser, enlisted at Lykens, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, for a three year term. They were recruited by James N. Douden (1836-1874), who they knew and who promised to be their captain. Douden was born in England. In 1860, he was married, living in Wiconisco, and working as a plasterer. Keiser reported that it was Douden who made the arrangements for teams to transport the Lykens and Wiconisco boys to Pottsville, no train service being available between those places. Early-on, Douden reportedly got sick and the men wouldn’t be sworn in unless they were assured he would be well enough to be their captain. For some unknown reason, Capt. James N. Douden resigned from the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry on 1 March 1862. The reason may appear in the pension application files, but they have not yet been consulted. There is no record that James Douden applied for a pension, but his widow Matilda did apply around 1890. However, she did not receive a widow’s pension. James Douden is buried in Methodist Episcopal Cemetery in Minersville, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, and his name appears on the Lykens G.A.R. Monument in Lykens Borough as one who never was a member of the post.

James N. Douden (1836-1874) – from Lykens G.A.R. Monument

James N. Douden (1836-1874) – from Lykens G.A.R. Monument

The trip to Pottsville began on Wednesday 25 September 1861. Keiser reported that the fifteen boys left from Lykens in two teams. “We drank at every hotel on our route… and all got pretty jolly.” It took nine hours to get to Pottsville. Along the way Keiser sprained his ankle jumping over a fence, an injury that may have bothered him into January when he reported it as a sore heel. Upon arriving in Pottsville, the recruits drew their first military article from the quartermaster sergeant – a blanket.

Through the first few months, the weather seemed enough of a factor to report on it almost daily. The rains began almost immediately. Then the winds blew the tents down so that most of the soldiers had to go into town to sleep. Keiser also reported receiving correspondence from a young lady, Miss Sally Workman, who he would later marry. Every letter he wrote and received was recorded in the diary.

On Monday 30 September 1861 the men took the oath and were officially in the service. As previously mentioned, they were concerned about the health of Capt. Dowden and would not be sworn until they were assured he would be their captain. Keiser and a few others were concerned enough to attempt a four mile trip to Minersville on 2 October to see how the captain was doing, but only got half way before realizing that they would be late getting back to camp. So, they returned.

Drilling took place during this period and a controversy erupted between some of the men and a would-be lieutenant, identified only as “Shelly,” who refused to take part in the drilling. Keiser said he wouldn’t drill unless the would-be lieutenant also participated, a refusal which caused him to be arrested. After explaining the situation to the officers, Keiser was released.

On 10 October 1861, Keiser again started out for Minersville to check on the captain. This time he met with Capt. Dowden and found him to still be sick, but recovering faster, and expected to re-join the company very soon. The captain returned to camp on 14 October and then took a few more days off to completely recover.

On 15 October, Henry Keiser and two others, James Ferree and Henry Romberger, went on a three-day furlough to Lykens. At first they took the train from Pottsville to Tremont, which they rode “free of charge.” From Tremont to Lykens the journey was by stagecoach, arriving at 9. p.m. The next day, after visiting his family on the farm, Keiser went into town to meet up with friends. The return trip took place the next day. Hereafter, Keiser referred to a train ride as “taking the cars.”

Henry Keiser’s twenty-first birthday was on 26 October and he received a song, “Truth Blends with Poetry” from a friend, and a “House Wife” (a sewing repair kit with needles, thread and buttons) from a young lady in Pottsville. On 29 October, Keiser’s father visited the camp to see how his son was adapting to military life. At the time of the visit, Daniel Keiser was 41, and had re-married in 1853 after the death of Henry’s mother. In 1850 he had been an innkeeper in Wiconisco Township, but by 1860, he returned to farming. The camp visit lasted until 1 November and both Henry and his father went around meeting with the other soldiers from the Lykens area. No doubt one of those visits was made with John C. Gratz.

Then came the rains again and the first hard frost occurred on 4 November. Finally, after more bad weather, the regiment was given marching orders. Training was complete and it was time to go south. The inland route taken by the regiment was recorded by Keiser. First, they marched two miles from the court House in Pottsville to Westwood where they “took the cars” to Ashland. At Ashland, they “changed cars” and proceeded to Sunbury where they boarded the Northern Central Railroad to head south though Millersburg and thence south to Baltimore. “I throwed a coat off and other stuff at the Millersburg Depot for my father as the train was passing on. Had time to call out ‘Daniel Keiser’ as I throwed it.” On 9 November at noon the train arrived at Baltimore. Then they “took the cars” to Washington, D.C. All along the route were soldiers guarding the rail line. On Sunday 10 November, they went into camp just south of Washington.

On 13 November, at the arsenal, the first weapons were issued – old “Harper’s Ferry Muskets” which the soldiers were promised were only temporary issues, rifles to follow. Other military issues were drawn from the quartermaster sergeant – a “splendid overcoat,” a pair of shoes, a new knapsack. Seemingly, the soldiers could draw whatever they needed in the way of clothing and supplies. Letters continued to find Henry and there were no complaints of delayed or lost mail. Likewise, Henry had plenty of time to write letters and visit with other regiments.

On 25 November, the regiment marched through Alexandria, Virginia, and found a place to set up camp, which the soldiers nicknamed “Camp Pottsville.” Two days later they drew their first ammunition. The decision was made to set up winter quarters at this spot, but then by 29 November, they had to move again.

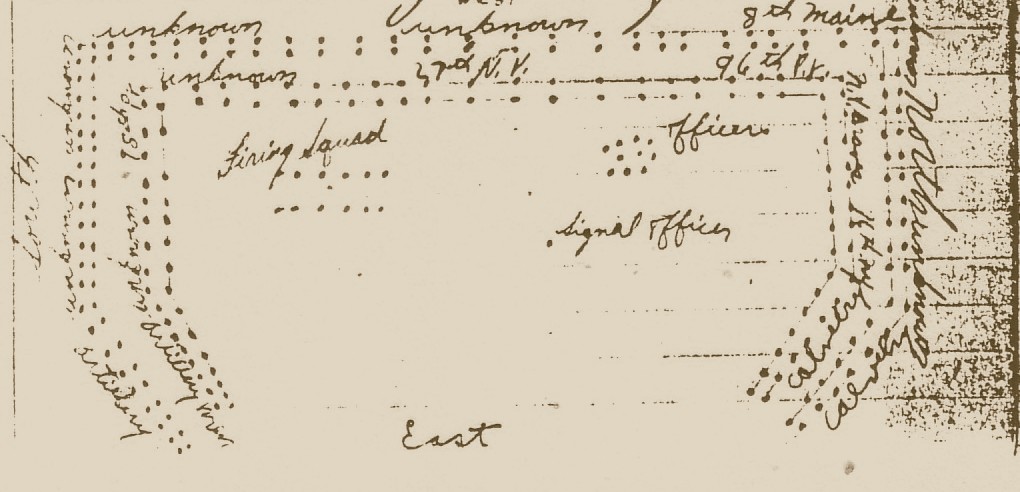

One major incident took place in camp which the superior officers undoubtedly used to insure loyalty and discipline. It was announced that a deserter who had defected to the rebels had been caught and that he would be executed by firing squad. All of the regiments in the area of the camps were to witness the execution. This deserter-defector was identified as“W. H. Johnson.” Keiser described the event in his diary and even drew a diagram of where each regiment was positioned during the execution. Gruesome details of Johnson’s death were noted – his leg kick as he took his last breath, the position and size of each of the wounds, and even the fact that an officer had to finish him off with a pistol as the firing squad had not completely done its work.

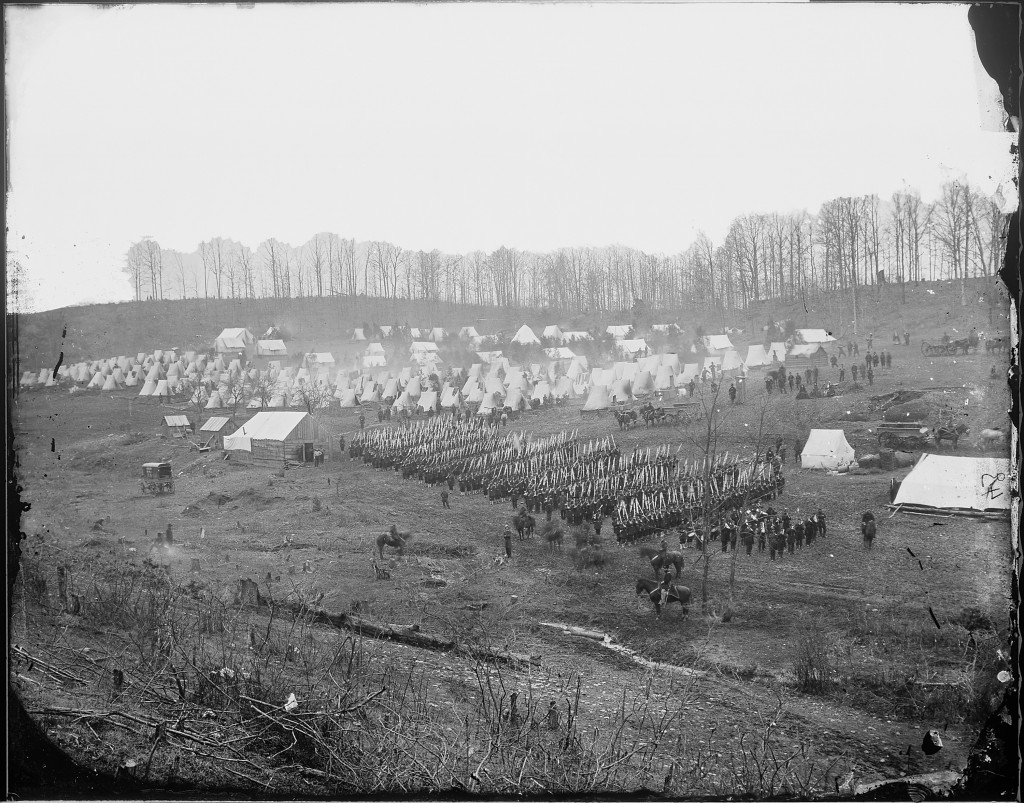

On the day before Christmas 1861, the regiment finally moved into its permanent winter quarters at Camp Northumberland.

Camp Northumberland – Photograph by Mathew Brady

Camp Northumberland – Photograph by Mathew Brady

For Christmas, all the men received new blankets – for which they were charged out of their pay allotment. On 7 January 1862, new Prussian rifles were received by all the men.

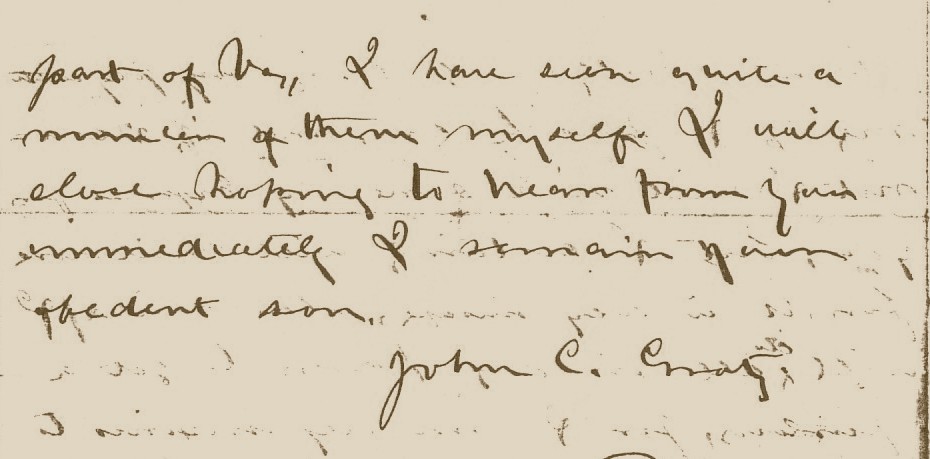

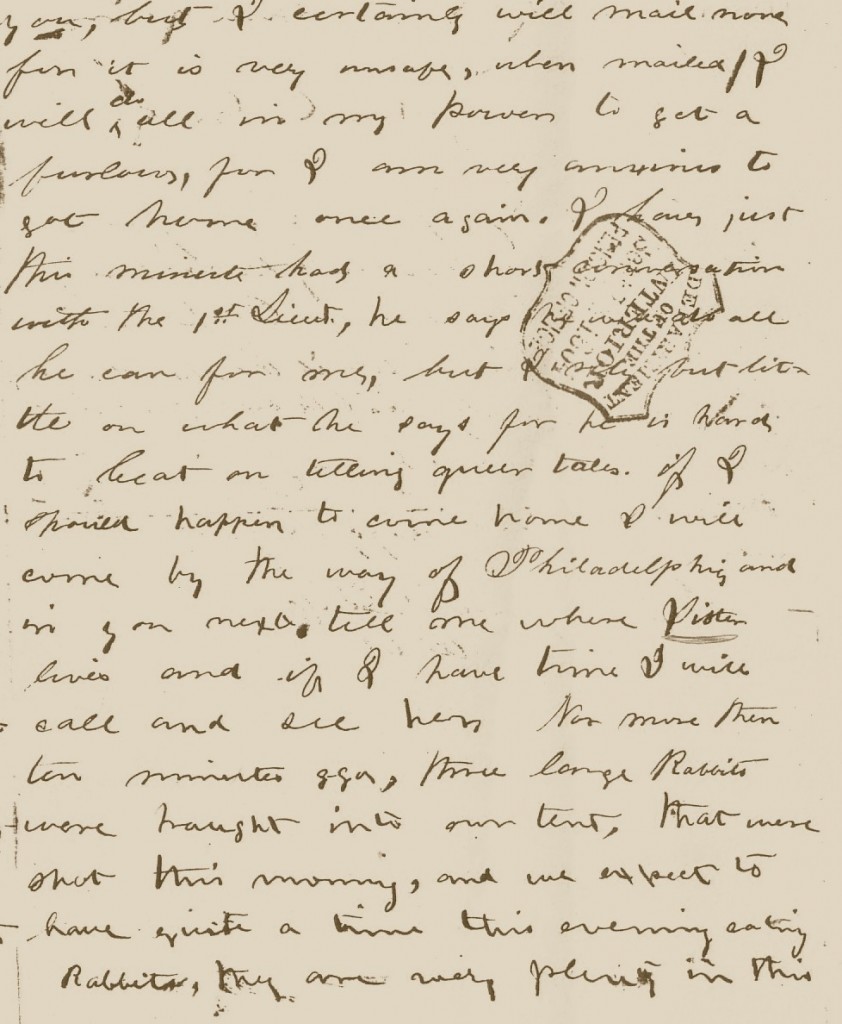

On 6 January 1862 , from Camp Northumberland, John Gratz wrote a letter to his mother:

Portions of Letter from John C. Gratz to his Mother (26 Jan 1862)

Portions of Letter from John C. Gratz to his Mother (26 Jan 1862)

Dear Mother,

I have been looking for a letter from you for some time, but all in vain, night after night I have been disappointed. I am commencing to feel quite uneasy, it is quite an unusual thing for you not to answer my letters. I feel confident that I have always answered your letter, although I confess not always immediately after received, but at a proper time nevertheless. The ground is now covered by snow for the first time this winter, every thing around us looks white, although pleasant say, as yet no very cold weather and here it is January. Thankful we should be, for such a blessing and also very few sick, particularly in our Company. I don’t think we have even eight or nine in the whole company, and they have principally Rheumatism, so far my health has been very good. This week we expect to be paid, I understand all the soldiers on this side of the Potomac, are to be paid within ten days from today. I expect our paymaster to be here about Thursday. I understand all the soldiers must have their discharge, from the nine months service, before they can receive the two dollars extra, and as I have sent mine to you, I don’t suppose I can get the two dollars unless you forward the discharge to me immediately. If it does not reach me in time I will try to use an oath writ, there is nothing lost by trying.

I will try to come home shortly, and bring my pay with me if I possibly can, and if not I will mail some by express for you, but I certainly will mail none for it is very unsafe when mailed.

I will do all in my power to get a furlough, for I am very anxious to get home once again. I have just this minute had a short conversation with the 1st Lieut, he says he will do all he can for me, but I rely little on what he says for he is hard to beat on telling queer tales. I would happen to come home I will come by way of Philadelphia and see you next. Tell me where Sister lives and if I have time I will call and see her no more than ten minutes. y-ya.

Three large Rabbits were brought into our tent, that were shot this morning, and we expect to have quite a time this evening eating Rabbits, they are very plenty in this part of Virginia. I have even quite a number of them myself. I will close anxious to hear from you immediately. I remain your obedient son.

John C. Gratz.

Keiser’s January diary entries reflect the weather – cold, snowy, rainy, muddy – water leaks through the roof of the cabins they had built. On 16 January 1862, Henry Keiser got a cold and fever and had to go to the company doctor for medicine. And on 17 January, John Gratz helped Henry by writing a letter for him. A few days later Henry felt fully recovered.

But the diary entry on 22 January was not good news. “John C. Gratz was taken sick last night with Typhoid Fever and was removed to the Regimental Hospital this morning.”

The rest of the story is known. John C. Gratz died of fever on 26 January 1862. Lt. Jacob Haas wrote to John’s mother informing her of his death. Later, on 1 Mar 1862, Lt. Haas was promoted to captain following the resignation of Capt. James N. Douden. The 96th Pennsylvania Infantry went on to suffer heavy casualties in the war. Henry Keiser was later wounded, but survived the war, and became a leading citizen of Lykens and active member of the Heilner Post of the G.A.R.

While John C. Gratz is not mentioned by name in Henry Keiser’s diary until 17 January 1862, both men most likely experienced the same things from the time they entered the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry until John’s death. Both men had served in the 10th Pennsylvania Infantry. Henry Keiser’s diary is in effect a chronicle of the last days of his friend John C. Gratz.

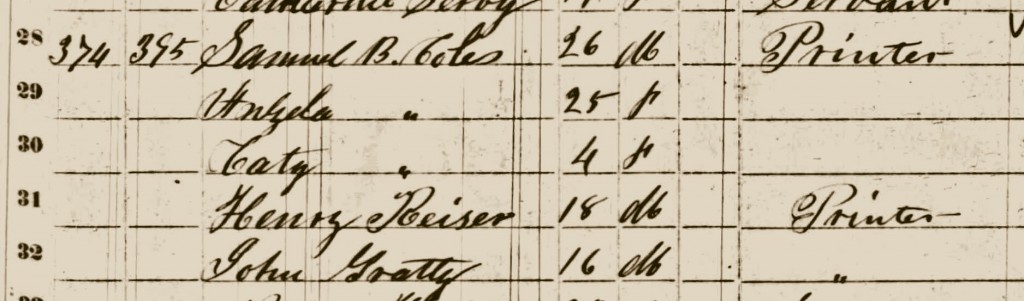

Until my recent, careful reading of the Keiser diary, I had not located John Gratz in the 1860 census. The clues were in the diary but can easily be missed. John’s occupation on enlistment in the military was “printer” and his residence was given as Lykens. In the diary, Henry Keiser refers to frequent letters he wrote to and received from an “S. B. Coles.” Henry had previously been located in the 1860 Census for Wiconisco Township (post office Lykenstown) as an 18 year old printer living in the household of Samuel B. Coles, who was a 26 year old printer. Also living in the same household was “John Grattz,” age 16, a printer. It appears that both John and Henry apprenticed together and lived together before the war!

Tomorrow, the post will focus on John Gratz’s mother and her attempt to get a pension based on her son’s military service. It is the final part in this four part series on John Gratz.

A copy of the letter from John Gratz to his mother is in the files of the Civil War Research Project. The text of the letter from John Gratz to his mother was previously published inA Comprehensive history of the Town of Gratz Pennsylvania. The portion of the Census of 1860 is from Ancestry.com. The Mathew Brady photograph of Camp Northumberland is from the Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD, 20740-6001 (unrestricted use). A photocopy of The Diary of Henry Keiser is in the collection of the Civil War Research Project.

;

;

Comments