Laura Keene Arrested at Harrisburg

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on January 12, 2012

She was born Mary Frances Moss on 20 July 1826 in Winchester, England. She married John Taylor on 8 April 1844 at St. Martin’s in the Field, England. Two daughters were born of the marriage. Her stage name of “Laura Keene” was taken about 8 Oct 1851, probably to hide fact that her husband became a convicted felon serving a life sentence in a penal colony in Australia. She became an actress as a way of supporting her daughters and decided that starting anew in America was the best for herself and for her family.

Laura Keene {Mary Frances [Moss] Taylor} fled an engagement in San Francisco and traveled to Australia with the actor Edwin Booth in an attempt to secretly locate John Taylor and get the marriage dissolved. She was unsuccessful in locating John Taylor and returned to the U.S. via of Hawaii. She then met John Lutz, a businessman from Washington, D.C. whose prominent family included a grandfather who had served with George Washington as a captain in the Revolution. Lutz became her business manager and was often represented as her husband – although he himself was married and had a daughter. Lutz traveled with her and protected her in the world of the theatre – clearly a man’s world in the 19th century.

Shortly after emigrating to America from England, Laura Keene had sent for her daughters and her mother. Through the help of John Lutz and his brother Francis Lutz, a prominent D.C. lawyer, arrangements were made for Keene’s daughters, Emma Taylor and Clara Taylor to attend a convent school in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. Laura forbade her daughters from divulging that she was their mother because that would have ruined her chances at a successful career – and would have exposed the charade she was presenting to the public. Laura had also converted to Catholicism and her travels as a married woman with the married or divorced Lutz would not be appropriate behavior. It was a successful ruse and the critics must have believed that Laura and John Lutz were married because no one presented information to the contrary.

While some authors consider her one of the leading women of the 19th-century American theater, other authors are highly critical of her. She is often credited with being a successful manager, although most of her successes were short-lived, and her career history was one of many ups and downs. When failure was approaching or when she found herself in trouble, her usual response was to get out of town as quickly as possible and start anew somewhere else.

Laura Keene‘s connections with Pennsylvania were strong. Prior to the Civil War, for several summers she vacationed with John Lutz near Tobyhanna in the Pocono Mountains. She also acted at playhouses in Philadelphia, Harrisburg and Pittsburgh.

However, she is best known to history as the star actress who was in the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on 14 April 1865, the night Lincoln was assassinated – and one of the main witnesses who identified John Wilkes Booth as the the man who jumped from the presidential box after the fatal shot was fired.

On the night of the assassination, Laura Keene‘s daughters were at the convent school in Georgetown. John Lutz, as her manager, should have been in Ford’s Theatre settling her accounts – she was not only the star that night, but John T. Ford had arranged for the proceeds to go to her as this was a benefit performance. It was Laura’s fortune that the president decided to attend that specific performance – a fact that would insure a full house and a good profit for her last night’s work in Washington. It was customary for the manager of a star to “count the house” during the third act and make settlement with the box office. Whether John Lutz was performing those duties when the shot was fired is unknown.

Was Laura Keene arrested in Washington as were others in the cast? This too is unknown. But a few days later, the following notice appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

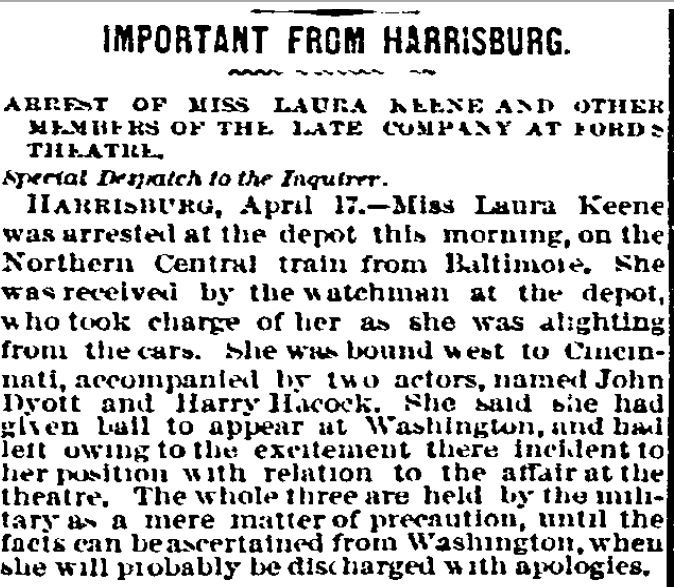

IMPORTANT FROM HARRISBURG

ARREST OF MISS LAURA KEENE AND OTHER MEMBERS OF THE LATE COMPANY AT FORD’S THEATRE

Special Despatch to the Inquirer

HARRISBURG, April 17 — Miss Laura Keene was arrested at the depot this morning, on the Northern Central train from Baltimore. She was received by the watchman at the depot, who took charge of her as she was alighting from the cars. She was bound west to Cincinnati, accompanied by two actors, named John Dyott and Harry Hacock [sic – should be Harry Hawk]. She said she had given bail to appear at Washington, and had left owing to the excitement there incident to her position with relation to the affair at the theatre. The whole three are held by the military as a mere matter of precaution, until the facts can be ascertained from Washington, when she will probably be discharged with apologies.

The fleeing from Washington of Keene and other members of her company was purportedly because she had to get to Cincinnati where she had been booked by Lutz for her next engagement. At Harrisburg, she could change trains from the Northern Central to the Pennsylvania line to Pittsburgh, thence to Cincinnati by a rather circuitous route. But Harrisburg was also a station stop on the Northern Central Railroad on the way through the Lykens Valley to Sunbury, then to Williamsport and on to Elmira, New York. The route was one of the most frequently traveled through the interior on the way to points in Canada. Surely Laura knew this as she had traveled the Northern Central through Harrisburg or connected at Harrisburg many times in the past. The authorities knew this also and were aware of those traveling to Harrisburg, those connecting on trains there, and those passing through. And the authorities were particularly aware of those heading out of the city where an assassination had taken place and where all roads out of the city were closed in the hours following the assassination. She would have had to have a special pass to leave Washington and to board the train at Baltimore.

Few historians writing about the assassination of Lincoln report about Laura Keene‘s arrest at Harrisburg. Those that do report it, generally ignore the details. Was she questioned by the authorities in Washington? Was she detained or arrested the evening of the crime? If she posted bail, who posted bail for her, how much was the bail and where did the money come from? Was John Lutz involved? Was John’s brother Francis Lutz involved? How did she arrange to get her personal belongings from Ford’s Theatre?- it had been sealed and closed by order of the Secretary of War. How was she able to get a “pass”to travel out of the city, not only for herself, but also for her two companions – and her baggage, which supposedly included a piano? Was she required to return to Washington at some point and testify? When she was arrested in Harrisburg, where was she held? Who arrested her and what did they suspect? If she had a “pass,” was she carrying it with her at the time of her arrest?

Miss Laura Keene, and Messrs. Dyott and Hawk, have been released, by order of Gen. Augur.

The small notice of Laura Keene’s release appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer the next day.

Special Despatch to the Inquirer.

HARRISBURG, April 19 — Miss Laura Keene and Messrs’ Dyott and Hawk were released by order of the Secretary of War the moment he heard of their unauthorized detention.

On 19 April 1865, five days after the “affair” at the theatre, it was again reported that Laura Keene, John Dyott, and Harry Hawk were released. By this time, Laura had arrived in Cincinnati, only to find that her performances had been canceled due to the period of mourning for Lincoln and the impending funeral.

If there was an order to release her that was received from the Secretary of War, as the brief article suggests, no written version of that order has surfaced.

Was John Lutz working on her behalf to enable her to get out of Washington? No specific facts have been found to confirm or deny his participation.

One of Laura’s two traveling companions was Harry Hawk, the only actor on the stage at the time Booth fired the fatal shot – and the person who supposedly positively identified Booth as the assassin. Hawk was questioned by authorities and his testimony is on record. Hawk was scheduled to perform with Laura in Cincinnati as was John Dyott, the other member of the cast who supposedly received a pass out of the city.

Records exist to show that nearly all the personnel at Ford’s Theatre (actors, stage hands, musicians, etc.) were arrested and questioned. John T. Ford himself was thrown in jail. The public suspected that the actors were complicit in the assassination and there were threats to burn down the theatre because of what had happened there. The theatre was under heavy military guard and the actors were not permitted to remove their possessions (including costumes), yet Laura Keene supposedly was allowed to remove her possessions – including the dress she wore in the closing act when the assassination took place, and a piano that traveled with her.

Another strange fact surrounding this incident was that the assassin’s brother Junius Booth, was finishing an engagement in Cincinnati the night of the assassination. Junius was arrested and held by authorities until it could be proven that he had nothing to do with his brother’s action. Yet Laura Keene was permitted to travel to Cincinnati.

Laura Keene had been on the same playbill in the past with John Wilkes Booth and some say she had been intimately involved with his brother Edwin Booth during the Australian tour when Laura was trying to find her husband. Edwin Booth, who was performing in Boston at the time of the assassination, was also arrested and it took special interference from Gen. Adam Badeau, a close friend and confidante of both Edwin Booth and Gen. Ulysses Grant to prove Edwin’s loyalty and secure his release.

Perhaps as part of the “re-building” of Laura Keene‘s reputation, a story began to surface that she had entered the presidential box, got down on the floor and cradled Lincoln’s head in her dress. This story was enhanced by the marketing of bloody swatches of what was said to be parts of the dress she wore that evening – and by the much-later “recollections” of eyewitnesses.

Historians have never explained why she was allowed to leave Washington when she was such a key witness in the identification of the assassin. If she had actually entered the presidential box as the legend states there would have been more reason to detain her as she would have been part of the efforts to save Lincoln’s life. There is no testimony on record from her although it is possible that she was informally questioned or formally questioned and the details have been lost. Laura Keene never made any statements regarding her own presence in the presidential box, regarding placing Lincoln’s head in her lap, and regarding her costume being covered with blood. It was others who spun the story into the legend that is oft told today.

The rebuilding of Laura Keene‘s reputation was partially successful, but perhaps due to her declining health, she was never again any more than a curiosity. She was also involved in law suits related to ownership rights to the play Our America Cousin. Ironically, it was Edwin Booth who claimed the right to perform the play and was successful in his claim. At least one historian has suggested that Laura didn’t pursue further legal action against Edwin because of the fear that her past marriage would be exposed – as well as possible infidelity with Booth that had taken place on the Australian tour.

After Laura Keene‘s death in 1873, she formally became part of the growing legends of the Lincoln Assassination, and other actors who were present that night latched onto the story of the bloody dress, and began to “confirm” it in what seemed more of a reputation-enhancing effort of their own careers or to show how patriotic they themselves were.

Laura Keene‘s arrest and release in Harrisburg remains a mystery as does her role and actions on the night of the assassination. The truth may never be known, but it is a fact that one incident involving characters who were witnesses to the Lincoln assassination was played out a few days later in Harrisburg, Dauphin County.

Future posts on Laura Keene will discuss how the legend of the bloody dress was developed and provide a bibliography for further study of the life of Laura Keene.

The portrait of Laura Keene at the beginning of this post is by Brady and is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. News clippings from the Philadelphia Inquirer are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia. A bibliography for Laura Keene will be provided in a later post.

;

;

What do you make of Joseph H. Hazelton’s eyewitness account? It was recorded in 1912, and Hazelton was a program boy at Ford’s Theater. He says after the shot, there was an awful hush in the theater, then Miss Laura Keene, who was in her dressing room, rushed to the stage and announced that President Lincoln had been shot by John Wilkes Booth.