John S. Eckel of Tremont – Fact-Checking a Story of His Confederate Service

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on October 28, 2015

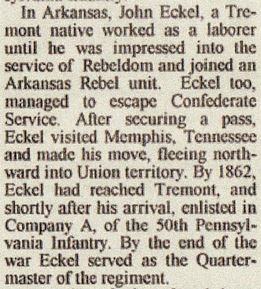

On 25 June 1993, a story appeared in the Citizen Standard (Valley View, Pennsylvania), entitled “Traitors: Some Locals Served with Confederates If Unwillingly.” The story was written by Mark T. Major. Included was a paragraph about John S. Eckel of Tremont:

In Arkansas, John Eckel, a Tremont native, worked as a laborer until he was impressed into the service of Rebeldom and joined an Arkansas Rebel unit. Eckel too, managed to escape Confederate Service. After securing a pass, Eckel visited Memphis, Tennessee and made his move, fleeing northward into Union territory. By 1862, Eckel had reached Tremont, and shortly after his arrival, enlisted in Company A, of the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry. By the end of the war Eckel served as the Quartermaster of the regiment.

John Eckel appears in the 1850 Census of Tremont as the 11-year old son of Henry Eckel and Mary [Weisel] Eckel. The family is still living in Tremont in 1860, but John is no longer in the household. Presumably, if the “Traitor” story above is accurate, he should appear somewhere in the area of Arkansas and would be working as a laborer. A census record for 1860 has not been located for him.

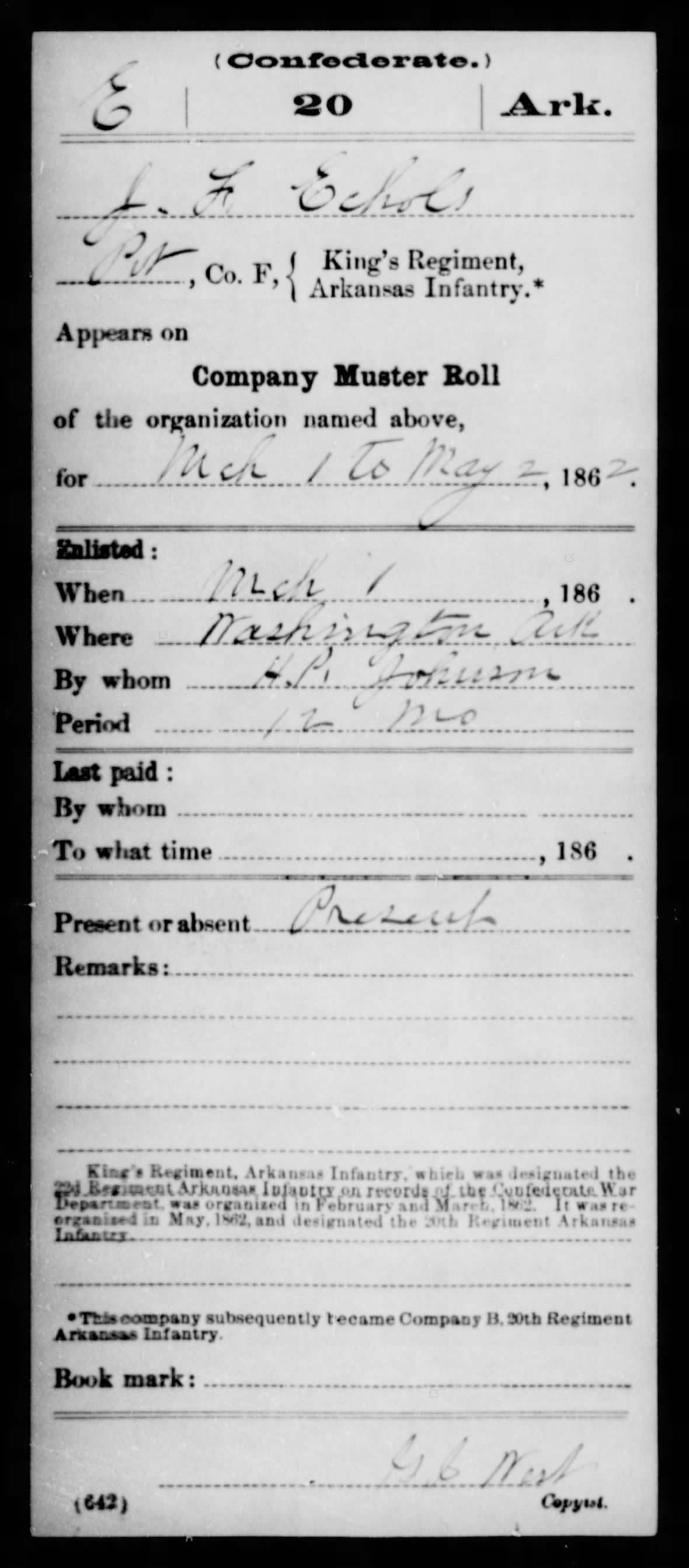

In searching the military records of Arkansas Confederate regiments, J. F. Echols was located in the 20th Arkansas Infantry, Company E, as a private. A military record card for that regiment notes that he enlisted at Washington County, Arkansas, for a term of one year on 1 March 1862. (See card below from Fold3).

There are a total of 15 cards available on Fold3 all of which describe some of the experiences of this soldier in that regiment – and, as shown below, his surname appears in various phonetic spellings. In addition to the card shown above, the following cards further support the belief that this person is the same person as described by Mark T. Major in his 1993 article:

#8 – John Echols – Private in Company B, 20th Arkansas Infantry – Roll of Prisoners of War captured by the Army of the Tennessee and sent to Memphis, Tennessee, 25 May 1863 – Captured near Vicksburg, 20 May 1863.

#9 – Jno Eckles – Private in Company B, 20th Arkansas Infantry – Prisoner of War at Fort Delaware, Delaware – captured Big Black, 16 May 1863 – transferred 20 September 1863 to Point Lookout, Maryland.

#10 – Jno Eccles – Private in Company B, 20th Arkansas Infantry -Prisoner of War – Captured at Big Black, 20 May 1863 – Sent from Fort Delaware, Delaware, to City Point, Virginia, for exchange.

#12 – John Eckles – Private in Company B, 20th Arkansas Infantry – Captured Big Black, 17 May 1863 – Roll of Prisoners of War Paroled Until Exchanged at Point Lookout, Maryland, 31 December 1863.

If the information on the above cards was accurately reported as in the actual military records, then the earliest that John Eckel could have left Confederate service was 20 September 1863 during his transfer to Point Lookout, Maryland, and the latest would have been 31 December 1863 when all the prisoners exchanges were said to be completed.

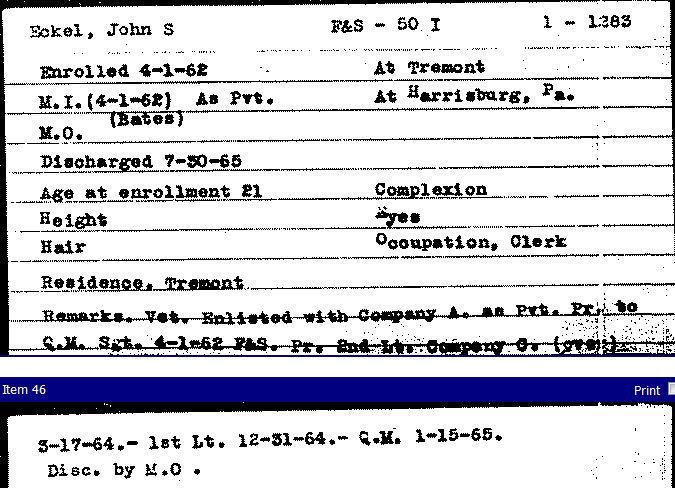

Turning to the Pennsylvania records, the card found at the Pennsylvania Archives gives the following information:

According to Bates, John S. Eckel enrolled on 1 April 1862 in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry at Tremont. There are two other index cards at the Pennsylvania Archives which report his original enrollment in Company C, although at the bottom of the above card, there is a statement that he originally enlisted in Company A as a Private. This is a confusing part of John S. Eckel‘s service in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry – i.e., the actual date on which he entered service in that regiment. On the card above, the date of “Muster In” is given as the same as the date of enrollment – but, the muster date is in parenthesis – something not often seen on other cards in the files available on-line. Could this mean that this 1862 date is not supported by the original records which are found at the Pennsylvania Archives?

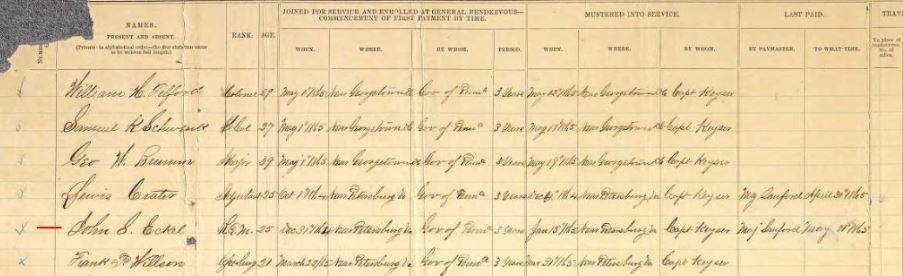

As of this writing, only some of the original muster sheets for this regiment are available on Ancestry.com. Unfortunately, only the re-enlistment sheet is presently available when searching for John S. Eckel. A portion of that sheet is shown below and can be enlarge by clicking on the image.

The sheet clearly shows that John S. Eckel did not enroll until 31 December 1864 and was not mustered into service until mid-January 1865. Both the enrollment and muster were near Petersburg, Virginia. This date is consistent with the release date as a P.O.W. at Point Lookout, Maryland.

When additional muster rolls appear on-line from the Pennsylvania Archives (via Ancestry.com), hopefully the original muster sheets from Company A and from Company C of the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry will be available to check to see if John S. Eckel appears on either or both of those original sheets.

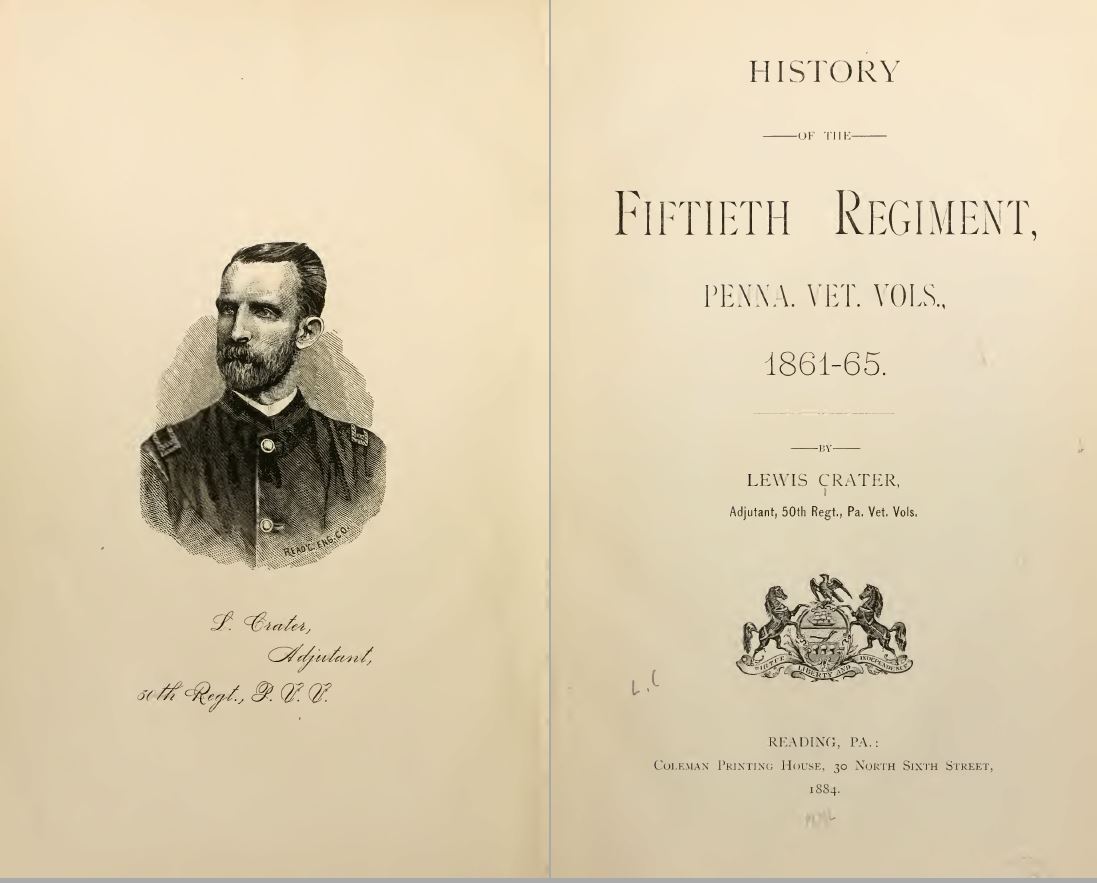

There is an available history of the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry, written in 1884 by Lewis Crater who was the Adjutant of the Regiment.

The book is available as a free download from the Internet Archive.

In the narrative text of the book, the name of John S. Eckel does not appear before page 76. That page describes the activities of the regiment occurring after 1 January 1864 when the re-enlistment took place. That information is reproduced below and includes an anecdote about John S. Eckel.

Nothing could more fully exemplify the patriotism of the regiment than its re-enlistment, 1 January 1864, under the circumstances in which it was placed. Having been on short rations since the siege of Knoxville, destitute of clothing, and many barefooted. Over two hundred miles from his base of supplies, in the middle of winter, constantly harassed by the enemy, neither General Burnside nor the Government could be blamed for this condition of affairs, hence the great question after re-enlistment, was, how to put the men in a condition to march back to Nicholasville, Kentucky, the snow being about six inches deep and the weather extremely cold. To protect the feet of the shoeless on the homeward march, shoes were made from raw hides, many of these, however, had to be abandoned during the first day’s march. The heat from within and the melting snow made them stretch, so as to be almost useless, hence many threw them away, and wrapped their feet with such clothing as could be spared. To add to our distress we were nearly perishing with hunger. The weather, part of the time, was so cold that the thermometer registered zero.

In the next paragraph, Crater continues to the arrival in Harrisburg, 6 February 1865, where the men in the regiment who had re-enlisted, were given a thirty-day furlough:

When we arrived at Mount Vernon, Kentucky, a store was found with a good supply of shoes on hand. Arrangements were made with the proprietor to furnish all the shoes required. After our arrival at Camp Nelson (at Nicholasville, Kentucky), the regiment was supplied with new clothing, blankets, provisions, etc. When it was drawn up in line preparatory to taking cars for Cincinnati, its appearance had improved wonderfully, each man having donned his new suit. After arriving in Cincinnati, we were quartered in the Fifth Street Market House for several days, waiting for our pay, after which we proceeded to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where we arrived 6 February 1865. Now for the first time in all our travels by railroad we were treated to first-class passenger cars (from Pittsburgh, over the Pennsylvania Railroad). The car furnished for the officers use was a very handsome and comfortable affair. In a few days after our arrival at Harrisburg, each man was given a thirty-day furlough and sent home.

Then Crater recounts some of the difficulties encountered by the regiment on the journey to Harrisburg – through Tennessee and Kentucky, etc., and includes the anecdote about Eckel:

After the regiment arrived at Rutledge, Tennessee, Quartermaster Sergeant John S. Eckel, (acting Quartermaster,) and Commissary Sergeant Lewis Crater were ordered by Colonel Christ to proceed to Buffalo Creek, with instructions to take charge of two mills there, and put the mills to work grinding rebel wheat, and when a wagon was ground to send it to camp. After having taken possession, Eckel remained at one mill and Crater at the other. When about half a ton of flour had been ground at Eckel’s mill, an officer of some Western regiment came along with a squad of men and ordered him away. On refusing to comply, the men were ordered to take possession, and Eckel placed under guard until all the flour was loaded on their wagon and taken away. The entire brigade received a portion of the flour secured at the other mill.

On the march from Knoxville to Rutledge, everything in the eatable line was looked upon only to be coveted. Notwithstanding, the troops were terribly in want of food, very little stealing was done. Most of the men had a little money, hence where provisions, etc,

On the march from Knoxville to Rutledge, everything in the eatable line was looked upon only to be coveted. Notwithstanding, the troops were terribly in want of food, very little stealing was done Most of the men had a little money, hence where provisions, &c. were offered at reasonable prices, very few of the men acted dishonestly. As an evidence of the voracious appetites engendered by the siege, five men, connected withe the commissary department, purchased three large geese and about half a peck of corn meal. The geese and corn meal were all cooked and eaten at one meal. The day before Christmas, 24 December 1863, a report reached camp that a supply train had reached Corps headquarters; all were anxiously wishing for the morning, when it was expected that provisions would be issued. Four men from Company C, however, were impatient and determined to proceed to headquarters, hoping that the sight of “hard tack” might do them good. Though the night was dark and rain falling rapidly, they soon found that the coveted provisions had been placed in a large tent, and a guard placed in a large tent, and a guard placed inside. The guard, however, had laid down and was sound asleep just inside the tent. One of the men stepped over the guard and carried out four boxes of hard bread, which they carried to camp. company C had a good Christmas dinner, the balance of the regiment, however, did not receive anything until late in the evening, hence they had nothing to eat nearly all day. While crossing the Wild Cat Mountain, on the march from Blain’s Cross Roads to Nicholasville, one of the baggage wagons upset, and before it could be gotten up on the mad again and loaded, night had set in. The men lay down upon the mountain top, on the frozen ground, and drawing a large tarpaulin over them for protection from the storm. During the night about four inches of snow fell, under which the men slept comfortably.

If the event (described above) involving Eckel took place at Buffalo Creek near Rutledge, Tennessee, as Crater states it did, then it may be possible to date the event through regimental records. According to the regimental history, from 5 to 26 December 1863, the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry was in pursuit of Longstreet’s Army to Blaine’s Cross Roads, Tennessee, the re-enlistment took place beginning on 1 January 1864, and in the period up through April 1864, the men moved to Annapolis, Maryland. This latter period, through April 1864, included the thirty-day furlough which began and ended at Harrisburg.

Crater then continues from the end of the furlough though arrival at Annapolis and encampment at Alexandria:

The thirty days furlough having expired on 8 March 1864, we rendezvoused at Camp Curtin until the 20th, when we were sent to Annapolis, Maryland, by steamboat from Baltimore. Our camping ground at Annapolis was that occupied by the regiment in October 1861. The regiment having been recruited to the minimum standard and fully organized and drilled, it was assigned to the Second Brigade, Third Division, Ninth Army Corps on the 21 April 1864, with Colonel B. C. Christ in command of the brigade. On 23 April 1864, the Ninth Corps moved from Annapolis, and on the 25 April, it was reviewed by President Lincoln, and then encamped near Alexandria.

Finally, Crater’s narrative moves into the Rapidan Campaign:

On the 27 April, the line of march was again taken up, and on the 28 April, we passed over the old Bull Run Battleground, resting at Warrington Junction on the 29 to 30 April. About noon on 5 May 1864, we crossed the Rapidan River at Germanua Ford, passing on to the front near the Wilderness Tavern, were formed a line of battle a little before three o’clock. We were heavily engaged on 6 May 1864, and at one time the rebels were around us in the form of a horseshoe, then we were double-quicked to a part of the field where our forces were stampeding. Our presence had the effect of infusing new energy into the disordered and broken ranks. The enemy were driven backward until our ammunition was nearly exhausted, when Lieutenant Colonel Overton sent Sergeant J. V. Kendall hack to the Brigade Commander, Colonel B. C. Christ, to ask for a fresh supply of ammunition, but there was none to be had. The request was made the second time, when word was sent back “Hold your ground at the point of the bayonet.” Colonel Overton did hold his ground, but at the cost of seventy men killed and wounded. During the night of the 6 May 1864, the regiment lay within fifty yards of the enemy’s line. Mr. Woodbury, in his history of the Ninth Corps, says: “Colonel Hartranft having found himself confronted by so strong a force as to make further progress impracticable. He did, however, succeed in maintaining his position close by the enemy’s entrenchments, where he was bravely supported by the brigade of Colonel Christ.

Thus from Crater’s description of the events of late 1863 and early 1864, it is only possible to conclude that John S. Eckel was with the regiment at some time during this period, but it is not not possible to draw any conclusion about when he first joined the regiment (i.e., 1862, late 1863, or early 1864).

No Pension Index Card has been located for John S. Eckel in Fold3. This is an indication that he never applied for a pension for his service in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry. If he did not sustain any injuries during the war, it would have been unlikely that he would have applied prior to 1890 when the rules for the awarding of a pension were significantly relaxed. It is therefore possible that he died prior to 1890.

A search for John S. Eckel in the Federal censuses of 1870 and 1880 produced no good results.

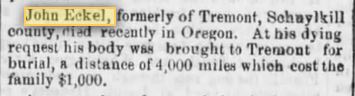

However, the following brief note was found in the Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania), 20 January 1876:

John Eckel, formerly of Tremont, died recently in Oregon. At his dying request, his body was brought to Tremont for burial, a distance of 4,000 miles which cost the family $1,000.

Thus, a conclusion could be drawn that John S. Eckel died in Oregon some time in late 1875 or early 1876. Local records from at or around the place he died could give an answer as to what he was doing there, whether he was married or had any family members with him, and how he died. At death, he would have been in his mid 30’s.

The evolution of the story that he was “impressed” into the Confederate service could have come from John Eckel himself – or may have been fabricated by a member of his family – to show that he was loyal to Union and did not willingly serve with the Confederate Army.

If John Eckel was buried in Tremont, his grave site has not yet been posted on Findagrave. There are a number of cemeteries in the Tremont area where he could have been buried. Perhaps a reader of this blog can locate the place of burial and submit a picture of the grave marker?

All in all, the story appears to be very believable that John S. Eckel of Tremont actually served in a Confederate regiment and that regiment was likely the 20th Arkansas Infantry. However, it was unlikely that his journey North was due to escaping, since he is found in the P.O.W. records, and his “visit” to Memphis was not on a “pass”, but the result of an official P.O.W. movement. Finally, it is possible that he ended up at Point Lookout, Maryland, where he was exchanged and released. From there, the story is murky, and whether he first returned to Tremont and then joined the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry, or joined first and then took furlough with the regiment while at Harrisburg, is unclear. It is also possible that he did escape while in the area of Memphis, Tennessee, that he then joined the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry, and that the P.O.W. records are for someone else who was mistaken for him.

Comments and suggestions are welcome and can be added to this post – or can be sent by e-mail. Hopefully, a reader of this blog will be able to bring forth additional facts about this story!

—————————

The news clipping is from Newspapers.com.

;

;

Look at the muster roll more carefully. It says that John S. Eckle enlisted into the 50th PA Infantry on 01 April 1862 at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg. There are two entries on the muster sheet because Eckle was commissioned as an officer on 01 March 1864. Besides the entry you included an image of; there is another entry for Eckle on the same page, 4th from the bottom in a list of people who were discharged, mostly to become officers. The 31 Dec. 1864 enlistment at Petersburg, VA is when he became an enlisted soldier again. My guess is that the difference between the enlistment date and the 15 Jan. 1865 muster-in date may be the result of some type of furlough.

Here is a link to record on Ancestry, if any reader would like to look at the muster roll themselves:

http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?ti=0&indiv=try&db=pamusterrolls&h=171866

Here is a link about Camp Curtin:

http://www.campcurtin.org/id5.html

The 01 April 1862 enlistment date makes it impossible for him to be the same John Eccles who was in the Confederate 20th Arkansas and a prisoner of war in 1863. Also, Eckle’s 01 April 1862 enlistment predates national Confederate conscription, although there could be local Arkansas historical considerations that I’m not aware of.

I wonder where the newspaper got it’s information about Eckle being in Arkansas, if it was just faulty research or if there was some family history information that formed the basis of that story. Also I was wondering what are some of the other names of soldiers that the article listed as being Confederates. I ask because I’m currently working on a research project looking at Union prisoners of war who enlisted into the Confederate Army, which includes soldiers from Pennsylvania.