Lykens Valley Coal Strikes During 1863

Posted By Jake Wynn on July 7, 2013

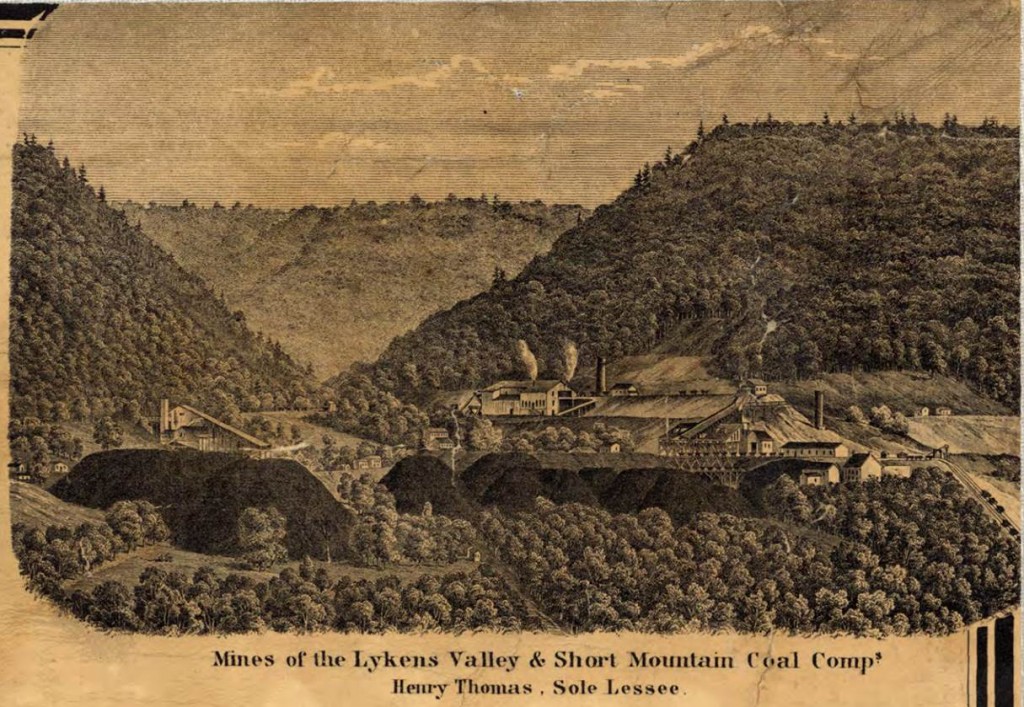

The Lykens Valley was mostly known for one major item in the years of the Civil War.

Anthracite coal.

This hard, stony coal burned hotter and longer than almost every other fuel available at the time, and the Lykens Valley anthracite was considered by many to be the best in the world. One article, published in Mining Magazine in 1853, called Lykens Valley coal, “the favorite fuel of Harrisburg.”

This coal was as much praised for its quality as its proximity to the Susquehanna River and the easily navigable route to the Chesapeake Bay. The Northern Central Railroad completed this benefit, by making speed yet another positive to the Lykens Valley coal.

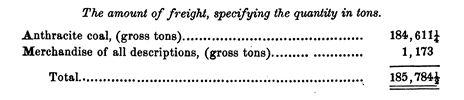

The mines at Lykens were very profitable by the time of the Civil War, supplying Central Pennsylvania and beyond with fuel to heat homes and drive the Union economy. The Lykens Valley Railroad, which was tied directly to the owners of the mines, recorded hauling 184,600 tons of anthracite coal from the Lykens Valley in 1862 alone.

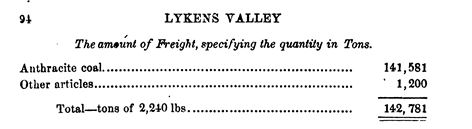

While the war years certainly helped establish the Lykens Valley’s economic prominence, something was amiss in 1863. The Lykens Valley Railroad reported only 141,000 tons of anthracite coal transported from the region. This is quite a significant drop in production from one year to another, especially during a time were peak production for war needs would have brought in large amounts of cash.

What could be the cause for such a precipitous drop?

The war had an unintended effect on the industry of the Lykens Valley and through the rest of the Anthracite Region. Many of those who supported the war, had gone off to fight the rebels. It just so happened that many of these men supported the Republican Party and its ideals of industry and free labor. Some of those who remained behind did not wish to join the war effort for political reasons. Democrats who opposed the war also wished to break some of the strength of industrialist Republicans who had a stranglehold over the anthracite region.

This drama played out in Schuylkill County over several years during the war, prompting the state and federal government to send troops to quell rebellion. Miners, many of them Irish, struck for higher wages and against the war and the draft provoked the government’s actions. While no evidence, as of now, suggests that violence such as this occurred in the Lykens coal field, it does not mean there were not disruptions.

Two incidents occurred in 1863 that may have contributed to the fall in production, both of which could have had dire consequences not only for the men and women of the Lykens Valley, but for most of Central Pennsylvania and possibly the Union war effort.

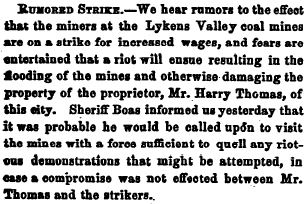

The Daily Patriot & Union of Harrisburg reported this on March 20, 1863:

“Rumored Strike. — We hear rumors to the effect that the miners at the Lykens Valley coal mines are on a strike for increased wages, and fears are entertained that a riot will ensue resulting in the flooding of the mines and otherwise damaging the property of the proprietor, Mr. Harry Thomas, of this city. Sheriff Boas informed us yesterday that it was probable he would be called upon to visit the mines with a force sufficient to quell any riotous demonstrations that might be attempted, in case a compromise was not effected between Mr. Thomas and the strikers.”

The situation seemed perilous enough that the Dauphin County Sheriff found it neccesary to bring an armed force with him to Lykens to potentially put down the riot. Apparently tensions eased, because the next day, the Patriot and Union reported:

“Settled.- We learn that the difficulty with the miners at the Lykens Valley coal mines has been satisfactorly adjusted, and that they have resumed work.”

Pressure still existed in the Lykens area, leading to a similar incident two months later when miners from Lykens again attempted to strike and were threatened with violence.

The Harrisburg Telegraph filed this report in their May 28, 1863:

“From Lykens Valley.– Strike among the Coal Miners.”

“Sheriff Boas was summoned to the upper end of the county Tuesday, to quell the disturbance at the Short Mountain Coal mines, caused by a strike among the workmen for an increase of wages. The Sheriff succeeded, without much difficulty, in pacifying the men to some extent, though they had not returned to their work when he left for Harrisburg.”

What conclusions does this leave us with?

The strike for higher wages at this present point tells us a lot about the miners and their situation at the time. They may have felt that this was a good time to press the issue for higher wages, because the work force was already strained by those who volunteered for war. This put the company owners in an awkward position, as many supported the war that took away much of their loyal workforce. Those who were left oftentimes supported workers’ rights or were new immigrants who were attempting to build a life in their new homeland.

The response tells us much as well. The forces of industry and the Republican-led government in Harrisburg moved quickly to squash any labor insurrection. From Lykens to Pottsville and beyond, any moves made for workers’ rights that involved miners moving off the job was quickly squelched by police or militia. While it did not lead to violence in the Lykens Valley, that did not mean it didn’t happen elsewhere…

Stay tuned for more posts as Central Pennsylvania commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Invasion of Pennsylvania and the battle of Gettysburg.

;

;

Comments