Charles Coffin’s Pennsylvania Campaign

Posted By Jake Wynn on June 23, 2013

The following comes from Charles Coffin’s book The Boys of ’61, which told of his experiences in the different armies of the Civil War. He was the war correspondent for the Boston Journal during the Civil War. Here is a chapter that tells specifically of his time in Pennsylvania and Maryland as the Confederates entered the North once again.

June, 1863.

The second invasion of the North was planned immediately after the battle of Chancellorsville. The movement of General Lee was upon a great circle,—down the valley of the Shenandoah, crossing the Potomac at Williamsport with his infantry and artillery, while General Stuart, with the main body of Rebel cavalry, kept east of the Blue Ridge to conceal the advance of the infantry.

General Hooker, at Fredericksburg, the first week in June, received positive information that Lee was breaking up his camp, and that some of his divisions were moving towards Culpepper. The dust-clouds which rose above the tree-tops indicated that the Rebel army was in motion. The Army of the Potomac immediately broke up its camp and moved to Catlett’s Station, on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, where intelligence was received that Stuart had massed the Rebel cavalry at Brandy Station for a raid in Pennsylvania.

General Pleasanton, commanding the cavalry, was sent with his entire force to look into the matter. He fell upon Stuart on the 9th of June, on the broad, open plains along the Rappahannock. A desperate battle ensued,—probably it was the greatest cavalry battle of the war,—in which Stuart was driven back upon the Rebel infantry, which was hurried up from Culpepper to his support. The object of the attack was accomplished,—Stuart’s raid was postponed and Lee’s movement unmasked. On the same day, Lee’s advanced divisions reached Winchester, attacked General Milroy, captured the town, the cannon in the fortifications, and moved on to the Potomac.

Cavalry charge.

Hastening to Pennsylvania, I became an observer of the great events which followed. The people of the Keystone State in 1862 rushed to arms when Lee crossed the Potomac, but in 1863 they were strangely apathetic,—intent upon conveying their property to a place of security, instead of defending their homes. In ’62 the cry was, “Drive the enemy from our soil!” in ’63, “Where shall we hide our goods?”

Harrisburg was a Bedlam when I entered it on the 15th of June.

The railroad stations were crowded with an excited people,—men, women, and children,—with trunks, boxes, bundles; packages tied up in bed-blankets and quilts; mountains of baggage,—tumbling it into the cars, rushing here and there in a frantic manner; shouting, screaming, as if the Rebels were about to dash into the town and lay it in ashes. The railroad authorities were removing their cars and engines. The merchants were packing up their goods; housewives were secreting their silver; everywhere there was a hurly-burly. The excitement was increased when a train of army wagons came rumbling over the long bridge across the Susquehannah, accompanied by a squadron of cavalry. It was Milroy’s train, which had been ordered to make its way into Pennsylvania.

“The Rebels will be here to-morrow or next day,” said the teamsters.

At the State-House, men in their shirt-sleeves were packing papers into boxes. Every team, every horse and mule and handcart in the town were employed. There was a steady stream of teams thundering across the bridge; farmers from the Cumberland valley, with their household furniture piled upon the great wagons peculiar to the locality; bedding, tables, chairs, their wives and children perched on the top; kettles and pails dangling beneath; boys driving cattle and horses, excited, worried, fearing they knew not what. The scene was painful, yet ludicrous.

General Couch was in command at Harrisburg. He had but a few troops. He erected fortifications across the river, planted what few cannon he had, and made preparations to defend the place.

General Lee was greatly in need of horses, and his cavalrymen, under General Jenkins, ravaged the Cumberland Valley. A portion visited Chambersburg; another party, Mercersburg; another, Gettysburg, before any infantry entered the State.

Ewell’s corps of Lee’s army crossed the Potomac, a division at Williamsport, and another at Shepherdstown, on the 22d of June, and came together at Hagerstown. The main body of Lee’s army was at Winchester. Stuart had moved along the eastern base of the Blue Ridge, and had come in contact with a portion of Pleasanton’s cavalry at Aldie and Middleburg. Hooker had swung the army up to Fairfax and Centreville, moving on an inner circle, with Washington for a pivot.

Visiting Baltimore, where General Schenck was in command, I found the Marylanders much more alive to the exigencies of the hour than the Pennsylvanians. Instead of hurrying northward with their household furniture, they were hard at work building fortifications and barricading the streets. Hogsheads of tobacco, barrels of pork, old carts, wagons, and lumber were piled across the streets, and patriotic citizens stood, musket in hand, prepared to pick off any Rebel troops.

Colored men were impressed to construct fortifications. They were shy at first, fearing it was a trap to get them into slavery, but when they found they were to defend the city, they gave enthusiastic demonstrations of joy. They went to their work singing their Marseillaise,

“John Brown’s body,” &c.

While writing in the Eutaw House, I heard the song sung by a thousand voices, accompanied by the steady tramp, tramp, tramp of the men marching down the street, cheering General Schenck as they passed his quarters.

How rapid the revolution! Twenty-six months before, Massachusetts troops had fought their way through the city, now the colored men were singing of John Brown amid the cheers of the people!

General Hooker waited in front of Washington till he was certain of Lee’s intentions, and then by a rapid march pushed on to Frederick. Lee’s entire army was across the Potomac. Ewell was at York, enriching himself by reprisals, stealings, and confiscations. General Hooker asked that the troops at Harper’s Ferry might be placed under his command, that he might wield the entire available force and crush Lee; this was refused, whereupon he informed the War Department that, unless this condition were complied with, he wished to be relieved of the command of the army. The matter was laid before the President and his request was granted. General Meade was placed in command; and what was denied to General Hooker was substantially granted to General Meade,—that he was to use his best judgment in holding or evacuating Harper’s Ferry! General Halleck was military adviser to the President, and the question between him and Hooker was whether Halleck, sitting in his chair at Washington, or Hooker at the head of the army, should fight General Lee. The march of Hooker from Fairfax to Frederick was one of the most rapid of the war. The Eleventh Corps marched fifty-four miles in two days,—a striking contrast to the movement in September, 1862, when the army made but five miles a day.

It was a dismal day at Frederick when the news was promulgated that General Hooker was relieved of the command. Notwithstanding the result at Chancellorsville, the soldiers had a good degree of confidence in him. General Meade was unknown except to his own corps. He entered the war as brigadier in the Pennsylvania Reserves. He commanded a division at Antietam and at Fredericksburg, and the Fifth Corps at Chancellorsville.

General Meade cared but little for the pomp and parade of war. His own soldiers respected him because he was always prepared to endure hardships. They saw a tall, slim, gray-bearded man, wearing a slouch hat, a plain blue blouse, with his pantaloons tucked into his boots. He was plain of speech, and familiar in conversation. He enjoyed in a high degree, especially after the battle of Fredericksburg, the confidence of the President.

I saw him soon after he was informed that the army was under his command. There was no elation, but on the contrary he seemed weighed down with a sense of the responsibility resting on him. It was in the hotel at Frederick. He stood silent and thoughtful by himself. Few of all the noisy crowd around knew of the change that had taken place. The correspondents of the press knew it long before the corps commanders were informed of the fact. No change was made in the machinery of the army, and there was but a few hours’ delay in its movement.

General Hooker bade farewell to the principal officers of the army on the afternoon of the 28th. They were drawn up in line. He shook hands with each officer, laboring in vain to stifle his emotion. The tears rolled down his cheeks. The officers were deeply affected. He said that he had hoped to lead them to victory, but the power above him had ordered otherwise. He spoke in high terms of General Meade. He believed that they would defeat the enemy under his leadership.

While writing out the events of the day in the parlor of a private house during the evening, I heard the comments of several officers upon the change which had taken place.

“Well, I think it is too bad to have him removed just now,” said a captain.

“I wonder if we shall have McClellan back?” queried a lieutenant.

“Well, gentlemen, I don’t know about Hooker as a commander in the field, but I do know the Army of the Potomac was never so well fed and clothed as it has been since Joe Hooker took command.”

“That is so,” said several.

After a short silence, another officer took up the conversation and said,—

“Yes, the army was in bad condition when he took command of it, and bad off every way; but it never was in better condition than it is to-day, and the men begin to like him.”

The army was too patriotic to express any dissatisfaction, and in a few days the event was wholly forgotten.

It was evident that a collision of the two armies must take place before many days, and their positions, and the lines of movement indicated that it must be near Gettysburg, which is the county seat of Adams, Pennsylvania, nearly forty miles a little north of east from Frederick, on the head-waters of the Monocacy. Rock Creek, which in spring-time leaps over huge granite boulders, runs south, a mile east of the town, and is the main stem of the Monocacy. Being a county seat, it is also a grand centre for that section of the State, contains three thousand inhabitants, and has a pleasant location, surrounded with scenery of quiet beauty, hills, valleys, the dark outline and verdure-clad sides of the Blue Ridge in the west, and the billowy Catoctin range on the south. Roads radiate in all directions. It was a central point, admitting of a quick concentration of forces.

The army commanded by General Meade consisted of seven corps.

1. Major-General Reynolds; 2. Major-General Hancock; 3. Major-General Sickles; 5. Major-General Sykes; 6. Major-General Sedgwick; 11. Major-General Howard; 12. Major-General Slocum.

As Ewell was at York, and as Lee was advancing in that direction, it was necessary to take a wide sweep of country in the march. All Sunday the army was passing through Frederick. It was a strange sight. The churches were open, and some of the officers and soldiers attended service,—a precious privilege to those who before entering the army were engaged in Sabbath schools. The stores also were open, and the town was cleaned of goods,—boots, shoes, needles, pins, tobacco, pipes, paper, pencils, and other trifles which add to a soldier’s comfort.

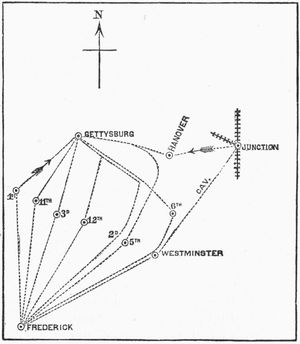

Cavalry, infantry, and artillery were pouring through the town, the bands playing, and the soldiers singing their liveliest songs. The First Corps moved up the Emmettsburg road, and formed the left of the line; the Eleventh Corps marched up a parallel road a little farther east, through Griegerstown. The Third and Twelfth Corps moved on parallel roads leading to Taneytown. The Second and Fifth moved still farther east, through Liberty and Uniontown, while the Sixth, with Gregg’s division of cavalry, went to Westminster, forming the right of the line.

The lines of march were like the sticks of a fan, Frederick being the point of divergence.

On this same Sunday afternoon Lee was at Chambersburg, directing Ewell, who was at York, to move to Gettysburg. A. P. Hill was moving east from Chambersburg towards the same point, while Longstreet’s, the last corps to cross the Potomac, was moving through Waynesboro’ and Fairfield, marching northeast towards the same point.

It was a glorious spectacle, that movement of the army north from Frederick. I left the town accompanying the Second and Fifth Corps. Long lines of men and innumerable wagons were visible in every direction. The people of Maryland welcomed the soldiers hospitably.

When the Fifth Corps passed through the town of Liberty, a farmer rode into the village, mounted on his farm-wagon. His load was covered by white table-cloths.

“What have ye got to sell, old fellow? Bread, eh?” said a soldier, raising a corner of the cloth, and revealing loaves of sweet soft plain bread, of the finest wheat, with several bushels of ginger-cakes.

“What do you ask for a loaf?”

“I haven’t any to sell,” said the farmer.

“Haven’t any to sell? What are ye here for?”

The farmer made no reply.

“See here, old fellow, won’t ye sell me a hunk of your gingerbread?” said the soldier, producing an old wallet.

“No.”

“Well, you are a mean old cuss. It would be serving you right to tip you out of your old bread-cart. Here we are marching all night and all day to protect your property, and fight the Rebs. We haven’t had any breakfast, and may not have any dinner. You are a set of mean cusses round here, I reckon,” said the soldier.

A crowd of soldiers had gathered, and others expressed their indignation. The old farmer stood up on his wagon-seat, took off the table-cloths, and replied,—

“I didn’t bring my bread here to sell. My wife and daughters set up all night to bake it for you, and you are welcome to all I’ve got, and wish I had ten times as much. Help your selves, boys.”

“Hurrah! hurrah! hurrah!” “Bully for you!” “You’re a brick!” “Three cheers for the old man!” “Three more for the old woman!” “Three more for the girls!”

They threw up their caps, and fairly danced with joy. The bread and cakes were gone in a twinkling.

“See here, my friend, I take back all the hard words I said about you,” said the soldier, shaking hands with the farmer, who sat on his wagon overcome with emotion.

On Tuesday evening, General Reynolds, who was at Emmettsburg, sent word to General Meade that the Rebels were evidently approaching Gettysburg. At the same time, the Rebel General Stuart, with his cavalry, appeared at Westminster. He had tarried east of the Blue Ridge till Lee was across the Potomac,—till Meade had started from Frederick,—then crossing the Potomac at Edwards’s Ferry, he pushed directly northeast of the Monocacy, east of Meade’s army, through Westminster, where he had a slight skirmish with some of the Union cavalry, moved up the pike to Littlestown and Hanover and joined Lee.

Riding to Westminster I overtook General Gregg’s division of cavalry, and on Wednesday moved forward with it to Hanover Junction, which is thirty miles east of Gettysburg. There, while our horses were eating their corn at noon, I heard the distant cannonade, the opening of the great battle.

Striking directly across the country, I rejoined the Fifth Corps at Hanover. There were dead horses and dead soldiers in the streets lying where they fell. The wounded had been gathered into a school-house, and the warm-hearted women of the place were ministering to their comfort. It was evening. The bivouac fires of the Fifth Corps were gleaming in the meadows west of the town, and the worn and weary soldiers were asleep, catching a few hours of repose before moving on to the place where they were to lay down their lives for their country.

It was past eight o’clock on Thursday morning, July 2d, before we reached the field. The Fifth Corps, turning off from the Hanover road, east of Rock Creek, passed over to the Baltimore pike, crossed Rock Creek, filed through the field on the left hand and moved towards Little Round-top, or Weed’s Hill as it is now called.

Riding directly up the pike towards the cemetery, I saw the Twelfth Corps on my right, in the thick woods crowning Culp’s Hill. Beyond, north of the pike, was the First Corps. Ammunition wagons were going up, and the artillerymen were filling their limber chests. Pioneers were cutting down the trees.

Reaching the top of the hill in front of the cemetery gate the battle-field was in view. To understand a battle, the movements of the opposing forces, and what they attempt to accomplish, it is necessary first to comprehend the ground, its features, the hills, hollows, woods, ravines, ledges, roads,—how they are related. A rocky hill is frequently a fortress of itself. Rail fences and stone walls are of value, and a ravine may be equivalent to ten thousand men.

Tying my horse and ascending the stairs to the top of the gateway building, I could look directly down upon the town. The houses were not forty rods distant. Northeast, three fourths of a mile, was Culp’s Hill.

On the northern side of the Baltimore pike were newly mown fields, the grass springing fresh and green since the mower had swept over it. In those fields were batteries with breastworks thrown up by Howard on Wednesday night,—light affairs, not intended to resist cannon-shot, but to protect the cannoneers from sharpshooters. Howard’s lines of infantry were behind stone-walls. The cannoneers were lying beside their pieces,—sleeping perhaps, but at any rate keeping close, for, occasionally, a bullet came singing past them. Looking north over the fields, a mile or two, we saw a beautiful farming country,—fields of ripened grain,—russet mingled with the green in the landscape.

Conspicuous among the buildings is the almshouse, with its brick walls, great barn, and numerous out-buildings, on the Harrisburg road. Beyond are the houses of David and John Blocher,—John Blocher’s being at the junction of the Carlisle and Newville roads. Looking over the town, the buildings of Pennsylvania College are in full view, between the road leading northwest to Mummasburg, and the unfinished track of a railroad running west through a deep excavation a half-mile from the college. The Chambersburg turnpike runs parallel to the railroad. South of this is the Lutheran Theological Seminary, beautifully situated, in front of a shady grove of oaks. West and southwest we look upon wheat, clover, and corn fields, on both sides of the road leading to Emmettsburg. A half-mile west of this road is an elevated ridge of land, crowned with apple-orchards and groves of oaks. Turning to the southeast, two miles distant, is Round-top, shaped like a sugar-loaf, rocky, steep, hard to climb, on its western face, easy to be held by those who have possession, clad with oaks and pines. Nearer, a little east of the meridian, is Weed’s Hill, with Plum Run at its western base, flowing through a rocky ravine. From the sides of the hill, and on its top, great boulders bulge, like plums in a pudding. It is very stony west of the hill, as if Nature in making up the mould had dumped the débris there.

Between Round-top and Weed’s there is a gap, where men bent on a desperate enterprise might find a passway. Between Weed’s and the cemetery the ridge is broken down and smoothed out into fields and pastures. The road to Taneytown runs east of this low ridge, the road to Emmettsburg west of it. A small house stands on the west side of the Taneytown road, with the American flag flying in front of it. There are horses hitched to the fences, while others are nibbling the grass in the fields. Officers with stars on their shoulders are examining maps, writing, and sending off cavalrymen. It is General Meade’s head-quarters. When the Rebel batteries open it will be a warm place.

Having taken a general look at the field, I rode forward towards the town, between Stewart’s and Taft’s batteries, in position on either side of the road. Soldiers in blue were lying behind the garden fences.

“Where are you going?” said one.

“Into the town.”

“I reckon not. The Rebs hold it, and I advise you to turn about. It is rather dangerous where you are. The Rebels are right over there in that brick house.”

Right over there was not thirty rods distant.

“Ping!”—and there was the sharp ring of a bullet over our heads.

General Howard was in the cemetery with his maps and plans spread upon the ground.

“We are just taking a lunch, and there is room for one more,” was his kind and courteous welcome. Then removing his hat, he asked God to bless the repast. The bullets were occasionally singing over us. Soldiers were taking up the headstones and removing the monuments from their pedestals.

“I want to preserve them, besides, if a shot should strike a stone, the pieces of marble would be likely to do injury,” said the General.

The flowers were blooming around us. I gathered a handful as a memento of the hour. Preparations were rapidly going on for the approaching struggle. North, west, and southwest the whole country was alive with Rebels,—long lines of men deploying in various directions, tents going up, with yellow flags above them on the distant hills, thousands of canvas-covered wagons, slowly winding along the roads, reaching as far as the eye could see towards Chambersburg, Carlisle, and Fairfield,—turning into the fields and taking positions in park. There were batteries of artillery, the cannon gleaming in the noonday sun, and hundreds of horsemen riding in hot haste on many a desperate errand.

While partaking of our refreshment, General Howard narrated the operations of the preceding day.

The original of this book can be online for free at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34843/34843-h/34843-h.htm

Stay tuned for more posts as Central Pennsylvania commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Invasion of Pennsylvania and the battle of Gettysburg.

;

;

Comments