Levan J. Warner – Killed at Wilderness, 6 May 1864

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on May 16, 2012

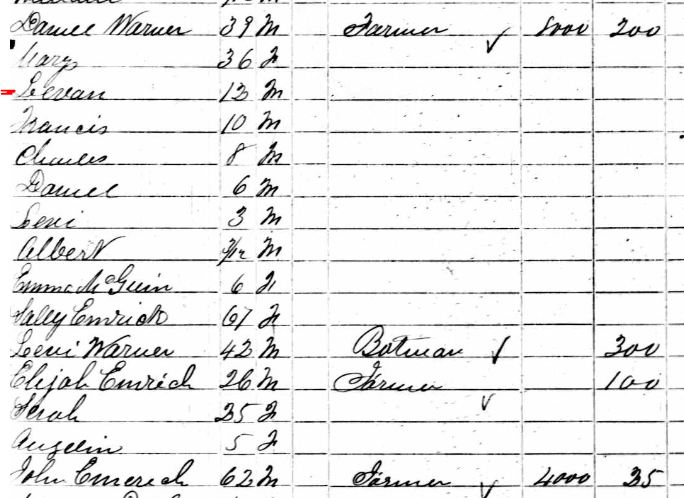

The post today is a continuation of a study of the men who served in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry. In 1860, Levan J. Warner was living on a farm owned by his father Daniel Warner in North Manheim Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Levan was then only 12 years old. Levan’s mother Mary [Emerick] Warner had six younger children to care for and was undoubtedly assisted by her mother, Sally Emerick, also living in the household. Others living there were Elijah Emerick, probably Mary’s younger brother, and his wife and young child. In addition, a Levi Warner, aged 42, was working as a boatman. The young Levan would soon be employed as a boatman, the occupation he would give upon enlistment in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry.

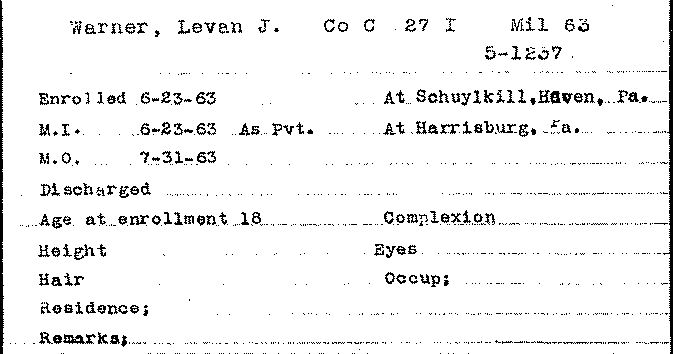

Out the outbreak of the Civil War, Levan J. Warner was clearly too young to volunteer. However, he was a member of the militia that was called into service for the Emergency of 1863 and he ended up serving from 23 June 1863 through 31 July 1863, however, he was not at Gettysburg.

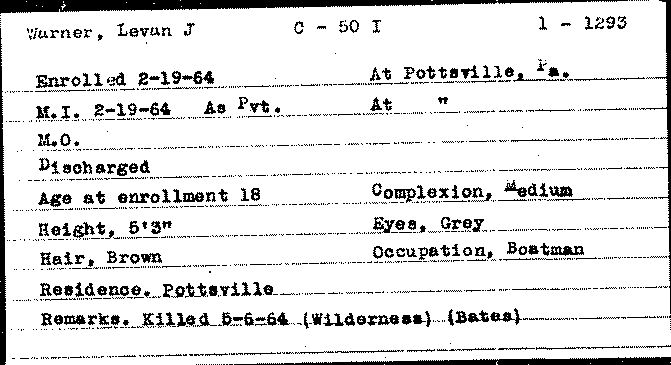

The militia service probably convinced the young Levan that he really was old enough to serve, so when the opportunity came in 1864 to enlist in the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry at Pottsville, Schuylkill County, he did so and was mustered in on 19 February 1864 at Pottsville. Although he gave his age as 18, he was probably closer to 16 in age.

Within only few months after joining the regiment, Levan J. Warner would be killed at the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia.

The following extracts are from The Union Army, Volume 6:

PRELUDE TO THE BATTLE

Wilderness, Virginia, 5 through 7 May 1864.

Army of the Potomac. On 9 March 1864, Maj.-Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was raised to the rank of Lieutenant-General and placed in command of all the United States armies in the field. The interval from that time until the 1 May 1864 was spent in planning campaigns, and in strengthening, organizing and equipping the several armies in the different military districts. Grant remained with the Army of the Potomac, which was under the immediate command of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, and which had for its objective the destruction of the Confederate army under command of Gen. Robert E. Lee. On 1 May 1864, the Army of the Potomac lay along the north side of the Rapidan River….

During the campaign the 18th Corps, commanded by Maj.-Gen. W. F. Smith, was transferred from the Army of the James to the Army of the

Potomac….Lee’s headquarters were at Orange Court House, about half way between Longstreet and the line along the Rapidan, from which point he could easily communicate with his corps commanders, and detachments of cavalry watched the various fords and bridges along the river.

Grant’s plan was to cross the Rapidan at the fords below the Confederate line of entrenchments move rapidly around Lee’s right flank and force him either to give battle or retire to Richmond. As soon as this movement was well under way, Gen. Butler, with the Army of the James, was to advance up the James river from Fortress Monroe and attack Richmond from the south. The region known as the Wilderness, through which the Army of the Potomac was to move, lies between the

Rapidan the north and the Mattapony on the south. It is about 12 miles wide from north to south and some 16 miles in extent from east to west. Near the center stood the Wilderness Tavern, 8 miles west of Chancellorsville and 6 miles south of Culpeper Mine Ford on the Rapidan. A short distance west of the tavern the plank road from Germanna Ford crossed the Orange & Fredericksburg Turnpike, and then running southeast for about 2 miles intersected the Orange Plank Road near the

Hickman farmhouse. The Brock road left the Orange & Fredericksburg Pike about a mile east of the tavern and ran southward to Spotsylvania Court House, via Todd’s Tavern. The first iron furnaces in the United States were established in the Wilderness, the original growth of timber had been cut off to furnish fuel for the furnaces, and the surface, much broken by ravines, ridges and old ore beds, was covered by a second growth of pines, scrub-oaks, etc., so dense in places that it was impossible to see a man at a distance of 50 yards. Between the Orange Plank Road and the Fredericksburg Pike ran a little stream called Wilderness Run, and north of the latter road was Flat Run the general direction of both streams being northeast toward the Rapidan into which they emptied. On the Orange Plank Road, about 4 miles southwest from the Wilderness Tavern, was Parker’s store.From the Confederate signal station on Clark’s Mountain… the Federal camps could be plainly seen. On 2 May 1864, Lee, accompanied by several of his generals, made a personal observation, saw the commotion in the Union lines, and rightly conjectured that an early movement of some kind was in contemplation. He accordingly directed his officers to hold their commands in readiness to move against the flank of the Federal army whenever the orders were given from the signal station. It was on this same day that Meade, by Grant’s instructions, issued his orders for the advance. Knowing that his every movement was observed by the enemy, he determined to cross the Rapidan during the night. At midnight on the 3rd the 5th and 6th Corps, preceded by [a] cavalry division, began crossing at Germanna Ford. The 2nd Corps, preceded by Gregg’s cavalry, crossed at Ely’s Ford farther down the river. On the evening of the 4th, Gen. G. K Warren’s [5th] Corps went into bivouac near the Wilderness Tavern….

During the night Lee sent word… to “bring on the battle now as soon as possible….” Grant joined Meade… and the two generals established their headquarters on the knoll around the Lacy house, a little west of the Wilderness tavern.

The Union loss in the battle of the Wilderness was 2,246 killed 12,037 wounded and 3,383 captured or missing. No doubt many of the wounded were burned to death or suffocated in the fire that raged through the woods….

Concerning the enemy’s casualties, Adam Badeau, in his Military History of U. S. Grant, says: “The losses of Lee no human being can tell. No official report of them exists, if any was ever made, and no statement that has been put forth in regard to them has any foundation but a guess. It seems however, fair to presume that as Lee fought outside of his works as often as Grant, and was as often repelled, the slaughter of the rebels equaled that in the national army. The grey coats lay as thick as the blue next day, when the national scouts pushed out over the entire battle-field and could discover no living enemy “

Levan J. Warner was killed in action at the Battle of the Wilderness on 6 May 1864. It is not known if his body was recovered or identified, and if so, his place of burial is unknown at this time.

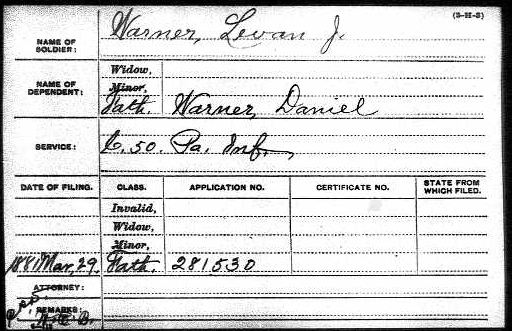

In 1881, Levan’s father, Daniel Warner, applied for a pension based on his Civil War service and death. The Pension Index Card shows that no pension was awarded to the father. The reason that the pension was not awarded to his father is probably in the application file which is available at the National Archives. No record has been found that anyone applied for a pension at the time of Levan’s death. He was probably not married, and his mother had other means of support.

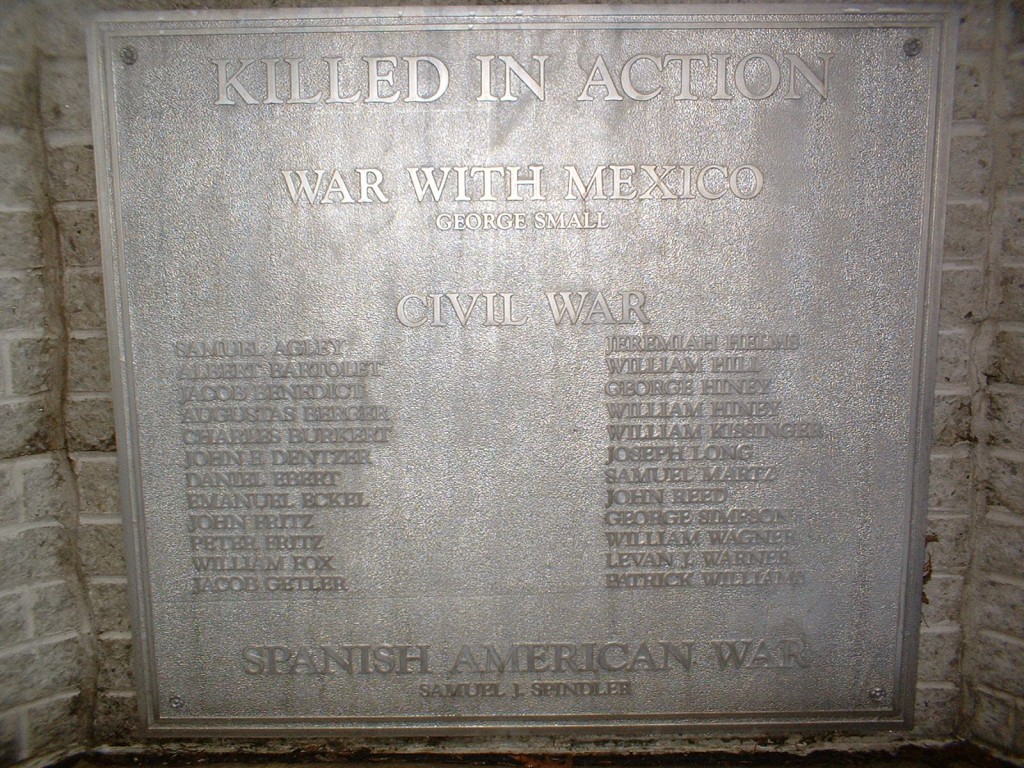

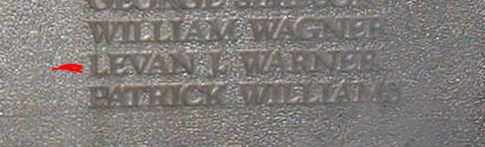

Schuylkill Haven was the home town of Levan J. Warner and a plaque there in Bubeck Park notes that he was killed in action in the Civil War. The plaque is pictured on the Schuylkill Haven web site.

Not much more is known about Levan J. Warner at this time.

Comments are welcome from readers. Pension records, not currently available on-line, are sought and a request is made to anyone who has already obtained them from the National Archives to submit copies for the Civil War Research Project.

Additional stories on the 50th Pennsylvania Infantry and the men who served in it can be found by clicking here.

;

;

Comments