Lincoln’s Birthday 1861

Posted By Norman Gasbarro on February 12, 2011

Abraham Lincoln was born on 12 February 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. In years after his death, his birthday would be celebrated in many places in the United States, and in some places as an official holiday. Today, he is included in our “President’s Day” holiday. In 1861, no former president had been recognized with a holiday, but there are a few references through American history where the birthdays of sitting or former presidents were publicly noted.

But in 1861, Lincoln had far more on his mind that the celebration of his own birthday, and with the mixed feelings toward him as the President-Elect, and with his already-begun-trip to Washington for inauguration, his 52nd birthday was the least of his concerns.

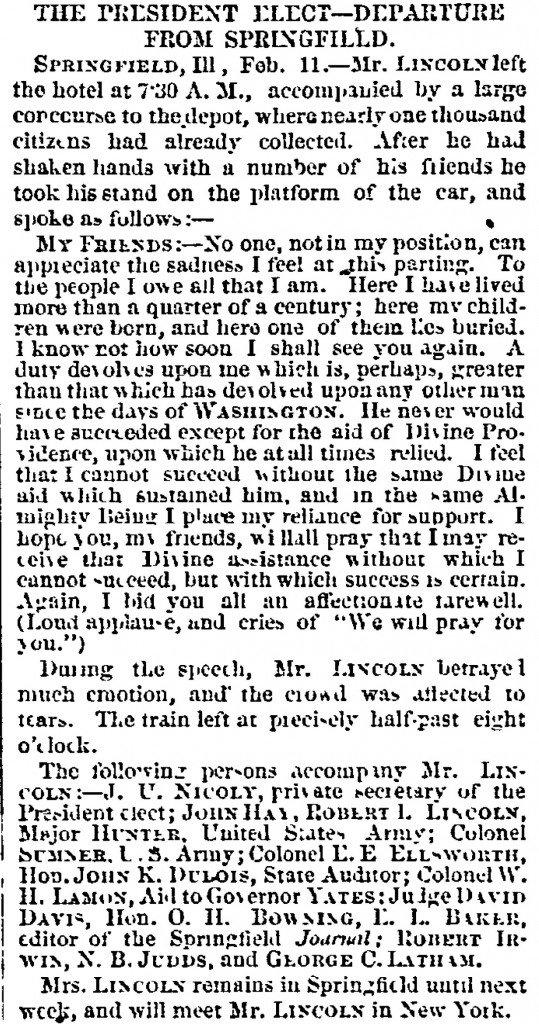

On 12 February 1861, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported a speech Lincoln made in Springfield, Illinois, telling the nearly one thousand residents at the railroad depot who had gathered see him off, that “I know not how soon I shall see you again.” The sadness of his departure was conveyed in words delivered to the crowd. He was leaving his home of more than twenty-five years, the home where his children were born, and the place where he buried one of them. He called upon the Almighty for divine support. “The crowd was affected to tears.”

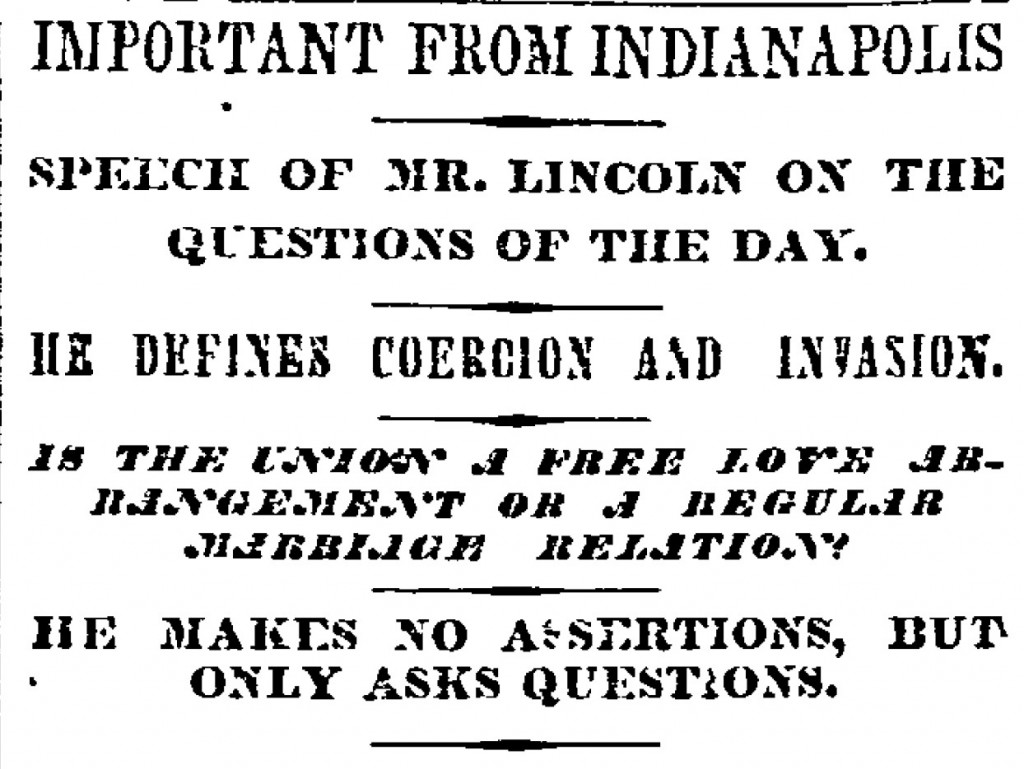

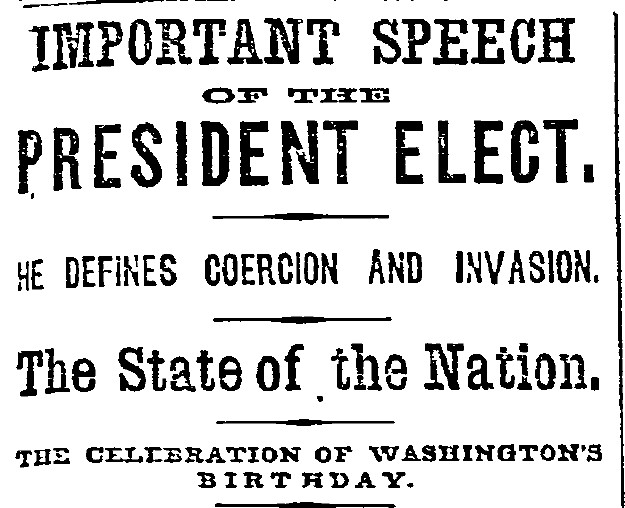

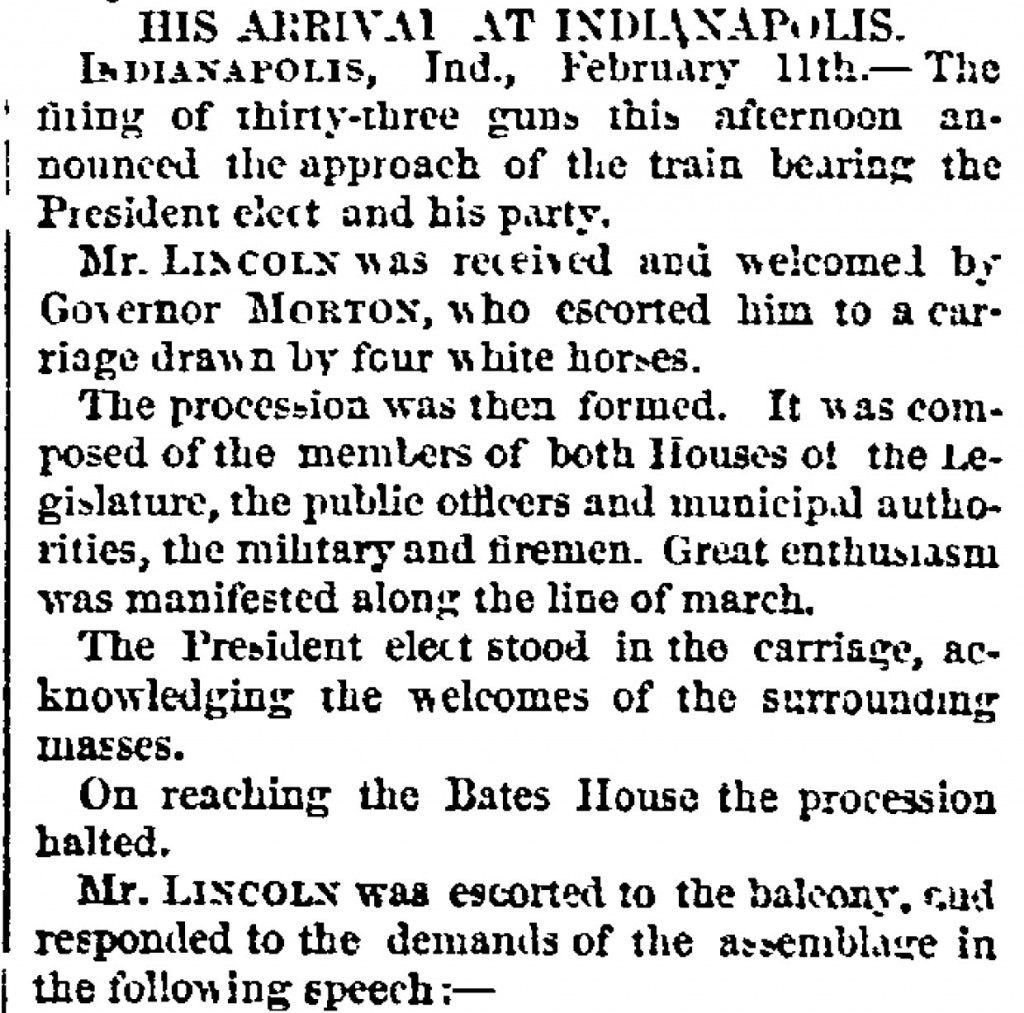

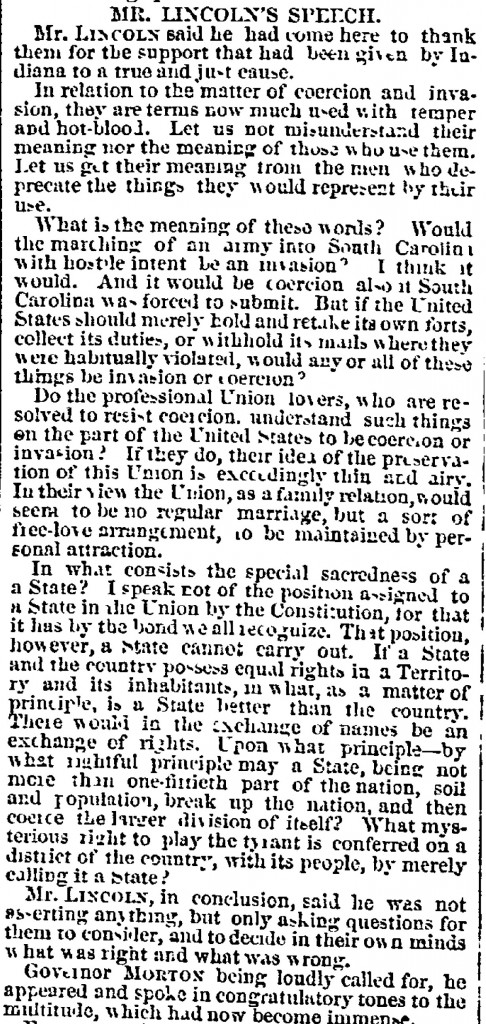

In the afternoon of 11 February 1861, the train arrived in Indianapolis, Indiana, welcomed by the governor and legislature and “surrounding masses” as he made his way to Bates House to speak to the assemblage there. He posed the questions on the minds of many gathered there – what to do about South Carolina and the federal property there – the whole issue of state’s rights and what was right and what was wrong. He gave no answers.

In the afternoon of 11 February 1861, the train arrived in Indianapolis, Indiana, welcomed by the governor and legislature and “surrounding masses” as he made his way to Bates House to speak to the assemblage there. He posed the questions on the minds of many gathered there – what to do about South Carolina and the federal property there – the whole issue of state’s rights and what was right and what was wrong. He gave no answers.

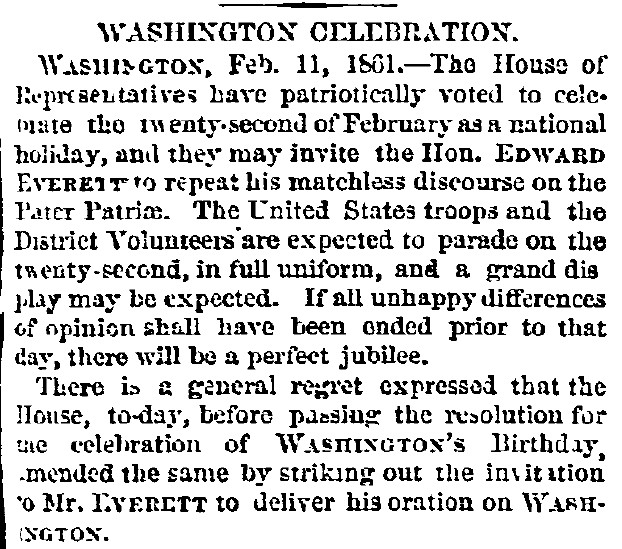

An event of 11 February 1861, largely overlooked in the context of things happening, was that the House of Representatives in the District of Columbia had voted to make the birthday of George Washington a national holiday. Considered in the bill was the invitation of the greatest orator of the day, the Hon. Edward Everett, to deliver one of his famous orations, “Pater Patrim,” But for some reason, perhaps because of the sectional divide (Everett was from Massachusetts),his invitation was struck by the House before the bill’s passage. Virginia, the home of George Washington, was still loyal to the Union at this date, and did not secede until after Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, the attack on Fort Sumter, and Lincoln’s call for troops. George Washington still belonged to the whole nation – but there may been fear that Everett would stray too far into the politics of the coming divide.

Ironically, Edward Everett would cross paths with Lincoln at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, 19 November 1863. Everett’s two-hour oration, delivered that day, is largely forgotten. He was followed by President Abraham Lincoln, who in just more than two minutes, delivered one of the epic speeches in American history. Lincoln re-stated the principles espoused in the Declaration of Independence and re-directed our efforts and our imagination from the more narrow constraints of “union” to the broader aims of true equality and freedom in a unified nation.

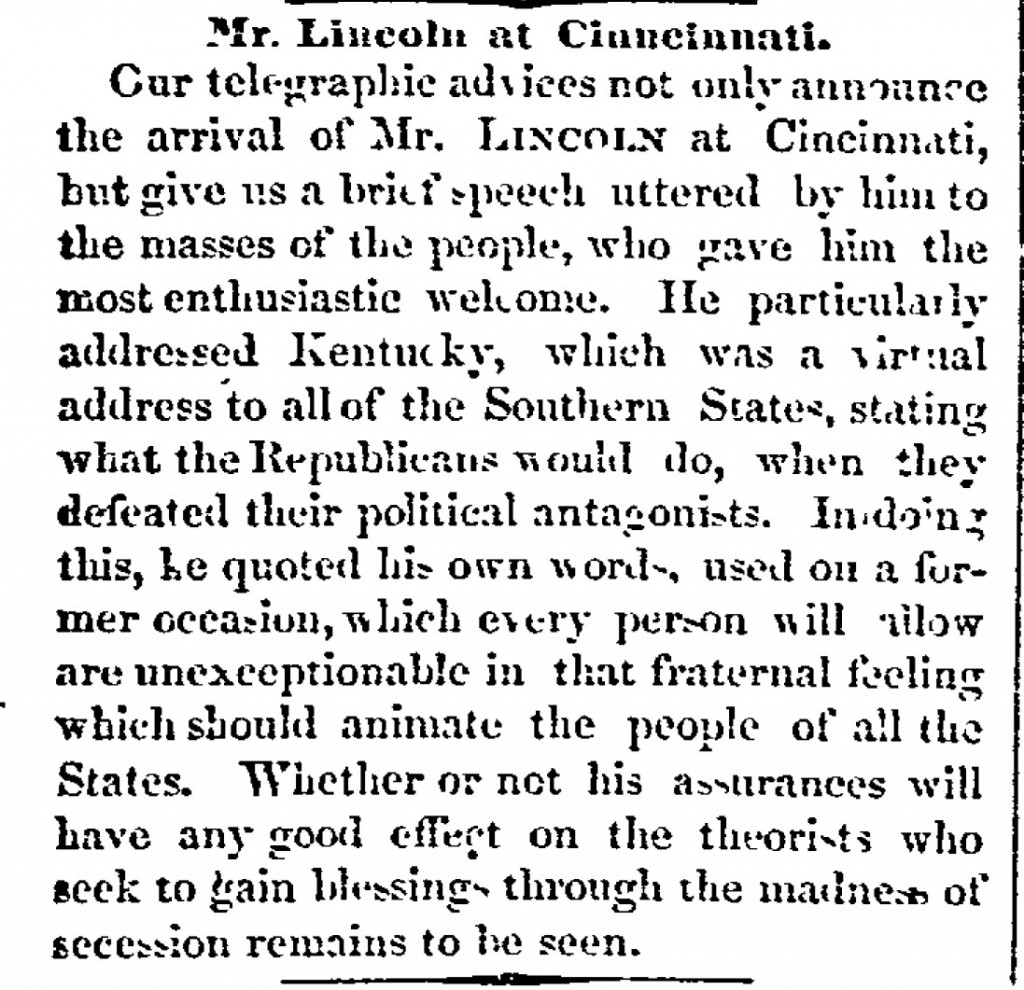

On 12 February 1861, Lincoln departed for Cincinnati, continuing his journey to Washington for the 4 March 1961 inauguration. Arriving in Cincinnati, he received an “enthusiastic Welcome.” There, he addressed the situation just across the Ohio River in Kentucky and made the remarks more general so as to apply to all the Southern states who were considering secession. Kentucky never did secede, but bordered those states that did.

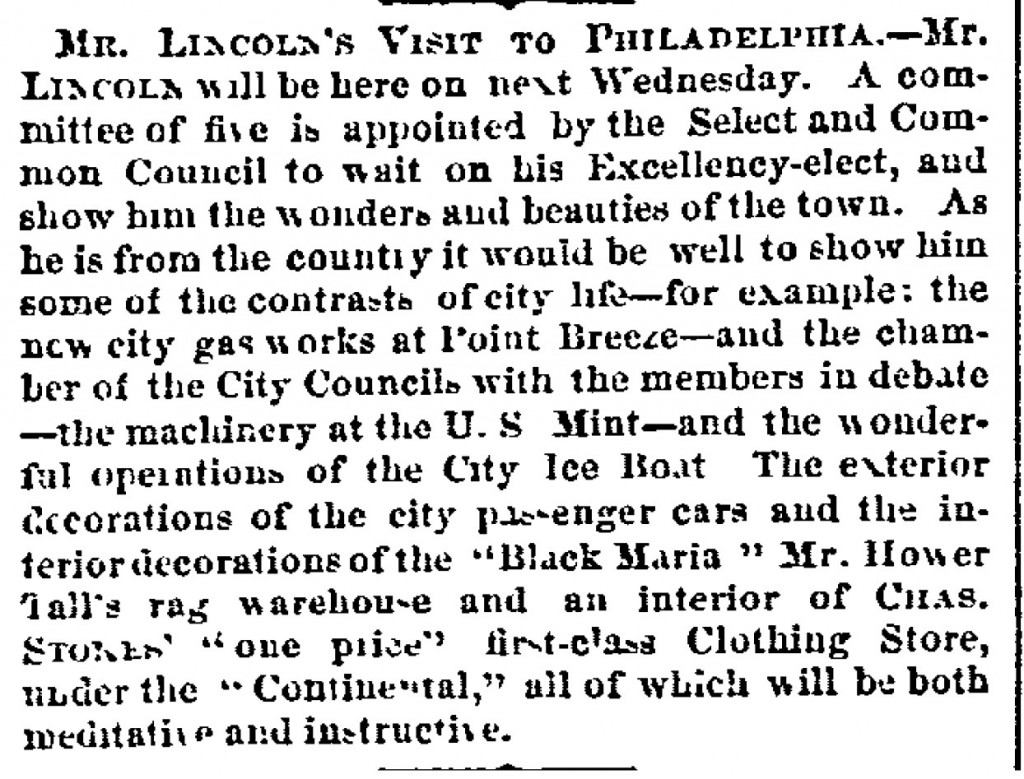

No references were found in the Philadelphia Inquirer to the fact that this was the President-elect’s 52nd birthday. But plans for the upcoming Philadelphia visit were noted:

MR LINCOLN’S VISIT TO PHILADELPHIA

Mr. Lincoln will be here on next Wednesday. A committee of five is appointed by the Select and Common Council to wait on his Excellency-elect, and show him the wonders and beauties of the town. As he is from the country it would be well to show him some of the contrasts of city life – for example: the new city gas works at Point Breeze – and the chamber of the City Councils with the members in debate – the machinery at the U.S. Mint – and the wonderful operations of the City Ice Boat. The exterior decorations of the city passenger cars and the interior decorations of the “Black Maria,” Mr. Hower Tall’s rag warehouse and an interior of Chas. Stokes’ “one price” first-class Clothing Store, under the “Continental,” all of which will be meditative and instructive.

Abraham Lincoln’s birthday never became a national holiday but was officially recognized in some states including California, Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey and New York. Washington’s birthday was officially established in 1880 as the first national holiday to honor an individual American citizen. In the beginning, it was celebrated on 22 February, Washington’s actual birthday. By 1971, in an attempt to create longer holiday weekends, the date was shifted to the third Monday of February, which always falls between 15 and 21 February and never on Washington’s actual birthday. By the mid-1980s, the date assumed the name of “President’s Day,” an attempt to honor all presidents.

The article with Lincoln’s speech of 11 February 1861, at his departure from his home in Springfield, Illinois, is shown below:

The article describing Lincoln’s speech as Indianapolis on 11 February 1861 follows:

Some information for this post was taken from Wikipedia articles on Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln’s Birthday, Washington’s Birthday, and Edward Everett. The picture of Edward Everett is from Wikipedia, was taken by Brady, and is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. “Clippings” from the Philadelphia Inquirer of 11 February 1861 and 12 February 1861 are from the on-line resources of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

;

;

Comments